Ernesto Hernández-Catá; January, 2014

The complete essay is here: STRUCTURE OF GDP, 2014. Hernandez-Cata

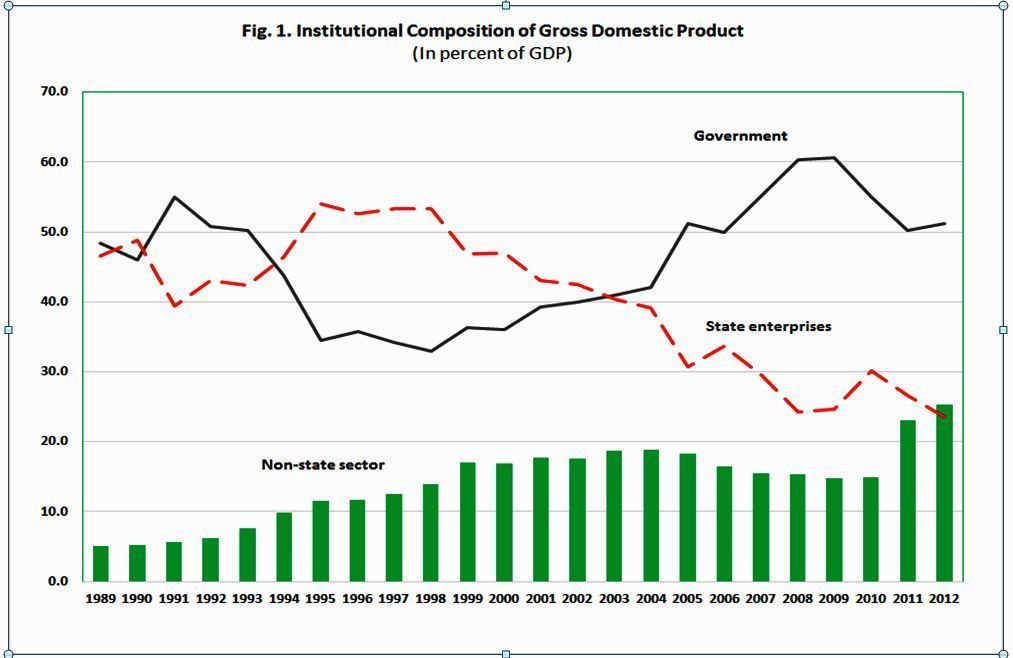

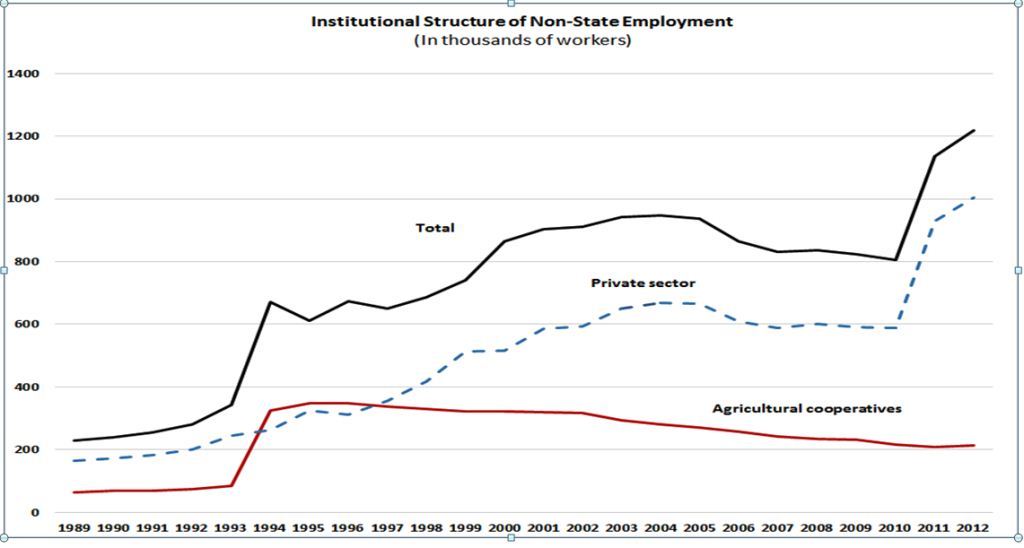

This paper presents estimates of Cuba’s gross domestic product (GDP) for the three principal sector of the economy: the government, the state enterprises, and the non-state sector. It estimates government GDP on the basis of fiscal data and derives non-state GDP from a combination of employment and productivity data. The article finds that the pronounced tendency for government output to increase faster than GDP was interrupted in 2010 and as the share of non-state production increased sharply. Nevertheless, the private share in the economy remains very low by international standards, and particularly in comparison to most countries in transition. The paper also derives estimates for gross national income. It finds that income is lower than GDP in the general government sector because of interest payments on Cuba’s external debt, while it exceeds production in the non-state sector owing to remittances from Cubans residing abroad.

The various estimates presented in this paper make it possible to reach a number of tentative conclusions.

ü The government share of GDP fell during the post-Soviet recession but then increased steadily all the way to 2009. The increase reflected the growth of current government expenditure; government investment—which accounts for the bulk of economy-wide capital formation—fell in percent of GDP. Total investment by all sectors also fell, to a very low level compared with the averages for other country groups and particularly for the emerging market and transition countries. The share of government spending declined from 2010 to 2011 following the financial crisis of 2008.

ü The share of the non-state sector GDP rose in the period 1993-1999 from a very low level in the Soviet-dominated period of the 1980’s. It changed little in the first decade of the XXIst century, but surged in 2011-2012 reflecting a transfer of employees form the state sector. Nevertheless, the non-state and private sector shares of the economy remains very small by international standards and notably by the standards of the countries in transition.

ü The relative importance of the state enterprises appears to have declined all the way from 1995 to 2009, but it has recovered somewhat since then.

ü National income in the government sector is lower than GDP because of interest payments on the external debt and, apparently, because of official transfers to foreigners.

ü By contrast, income in the non-state sector exceeds GDP by a growing margin, essentially because of dollar remittances from Cuban-Americans abroad. Thus, in that sector income from domestic production is being increasingly supplemented by income from abroad.

ü There is a statistically significant tendency for government current spending to crowd out the output of the state enterprises. Non-state output, on the other hand, appears to evolve mainly in response to official decisions to liberalize or to repress the non-state sector

Finally, there is a major problem whose resolution is beyond the scope of this article but which must at least be noted. The Cuban authorities assume that data for transactions denominated in foreign currency should be translated into local currency at the fixed exchange rate of one peso (CUP) per U.S. dollar. Under this convention (which is retained in this paper) dollar values are identical to peso values. Historically, however, the exchange value of the peso applicable to households and tourists has been much lower and it is currently CUP 24 per dollar. Clearly, the 1:1 exchange rate assumption introduces major distortions in the national accounts and in the balance of payments. For example, the peso value of exports of at least some goods and services (nickel, sugar and tourism among others) is grossly under estimated, while the dollar value of consumption is grossly over-estimated. In the income accounts, the dollar value of wages (mostly denominated in CUPs) is overestimated while the peso value of private remittances is under-estimated—although this is partly offset by an under-estimation of the peso value of interest payments abroad.

The task of disentangling all the elements of bias introduced by the use of a 1:1 conversion factor would be daunting. For the time being the corresponding distortions would have to be accepted, although they should be recognized. The good news is that the Cuban authorities are in the process of unifying the existing multiple exchange rate system, too slowly hélàs, but fairly surely. One important result of this change will be to the adoption of a single exchange rate for all transactions and all sectors, as well as for the purpose of statistical conversion.