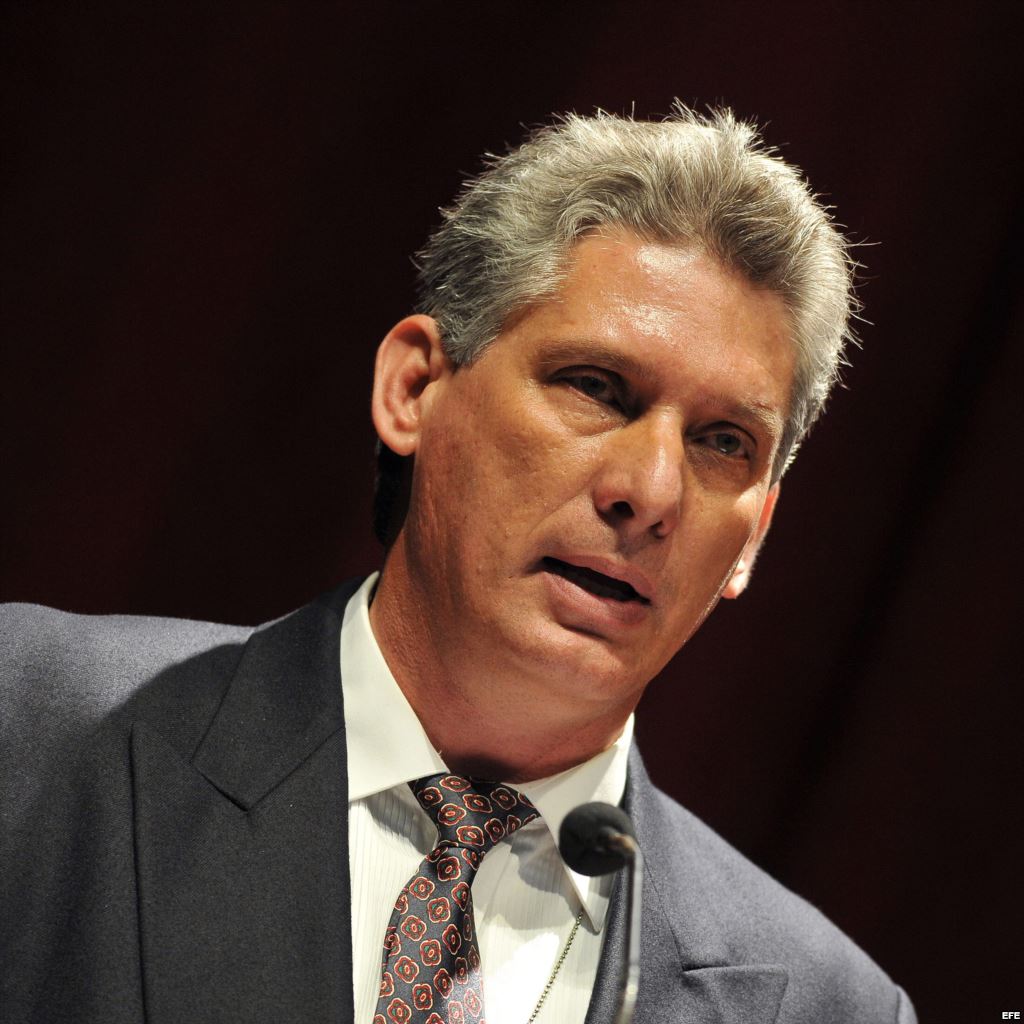

Roberto Veiga González, left, and Lenier González Mederos

Roberto Veiga González, left, and Lenier González Mederos

By VICTORIA BURNETT, New York Times, November 21, 2014

Original here: EXTOLLING MODERATION

MEXICO CITY — FROM a lectern covered in a lacy, white cloth at a provincial Cuban church center last month, Roberto Veiga González and Lenier González Mederos took turns talking before about 60 intellectuals and activists about the value of political dialogue. Not, perhaps, the most electrifying topic, but if politics is the art of the possible, it is a skill that the pair hope Cubans can master after wearying years of bombast and vitriol.

“A plurality of views can coexist,” said Mr. Veiga, a lawyer and former magazine editor who, with Mr. González, has come to represent an emerging, less confrontational, approach to Cuban politics.

Looking over his reading glasses at the opening of a two-day seminar on Cuban sovereignty, he added, “It is possible to think differently but work together.”

If that is a difficult view to peddle in Washington, it is an even tougher sell in Cuba, where the state has, for decades, stifled debate and the government and its opponents are bitterly divided.

“We Cubans are the enemies of moderation,” said Mr. González, a former journalist, by telephone from Havana.

Mr. González, 33, and Mr. Veiga, 49, have been criticized as too timid by some in the opposition. But their dogged efforts to get Cubans talking have won them a strong following in Cuba’s tiny civil society.

They are leading figures in an incipient culture of debate that has taken root in recent years, largely as President Raúl Castro has allowed greater access to cellphones and the Internet, and lifted some restrictions on travel, but also as the United States has lifted restrictions on Cubans’ visiting their relatives.

The pair reflect a breakdown of the binary politics of pro- and anti-Castro Cubans that dominated for decades, and the development of a more diverse range of opinions, especially among younger Cubans, as they look to the era that will follow the Castros’ deaths.

As editors, until recently, of a Roman Catholic magazine, the pair have created a space where dissidents, dyed-in-the-wool communists, artists, exiles, bloggers and academics can discuss national issues, both in print and at seminars held in a Catholic cultural center in Old Havana.

Their new project, Cuba Posible — part forum, part online magazine, part research organization — aims to do the same, and will test the government’s threshold for debate as well as Cubans’ appetite for finding a third way.

Serious and circumspect, Mr. González and Mr. Veiga lack the caustic eloquence of Yoani Sánchez, whose blog Generation Y has millions of readers, and the daring of some dissidents. They tread carefully, advocating political change without rupture and keeping some distance from the Castros’ most outspoken adversaries.

THE two have become a double act, hosting debates together, traveling together for conferences and studying together in Italy for doctorates in sociology (Mr. González) and political science (Mr. Veiga).

Both are Roman Catholics. Mr. González was raised in a religious family, and Mr. Veiga joined the church as an adult. Their faith, they say, fuels their quest for solutions.

“We saw that there was a whole range of people who didn’t have anywhere to express themselves,” Mr. González said, adding, “We have a Christian calling to try to mend something that is broken.”

Still, their styles are different: Mr. Veiga, a lawyer from the city of Matanzas, about 60 miles east of Havana, is preoccupied with issues like constitutional overhaul and chooses his words carefully.

Cuba Posible does not advocate democracy, he said in a telephone interview, but promotes dialogues that incorporate “discernment of the question of how to advance toward fuller democracy.”

Mr. González, who studied media and communications at the University of Havana, is more direct than Mr. Veiga and, acquaintances say, less patient.

Cubans and political analysts say the pair are trusted and respected, even by those whose posture is more confrontational. Katrin Hansing, a professor of anthropology at Baruch College, who has known both men for years, said they were thoughtful and courageous.

When they took over Lay Space, the Cuban Catholic magazine, in the mid-2000s, Mr. Veiga and Mr. González refocused it, to include essays from academics, economists and political scientists. They wrote editorials on the timidity of the government’s economic overhauls and the options for a transition to democracy.

Their debates drew a spectrum of voices that Philip Peters, president of the Cuba Research Center in Virginia, said he had found nowhere else in Cuba. Some discussions were slow and academic, others surprisingly frank.

The impact of their efforts to broaden debate is hard to determine. Mr. Veiga said officials had told him they followed what was said. Still, he said, “we need many more spaces, mechanisms and guarantees so that citizens’ opinions can effectively interact with the public powers.”

Mr. Veiga and Mr. González are not the only, nor the first, Cubans debating national politics. Publications, including New Word, the magazine of the Archdiocese of Havana, have bluntly urged much faster economic changes. Temas, a cultural magazine, has for years held monthly discussions that are open to the public.

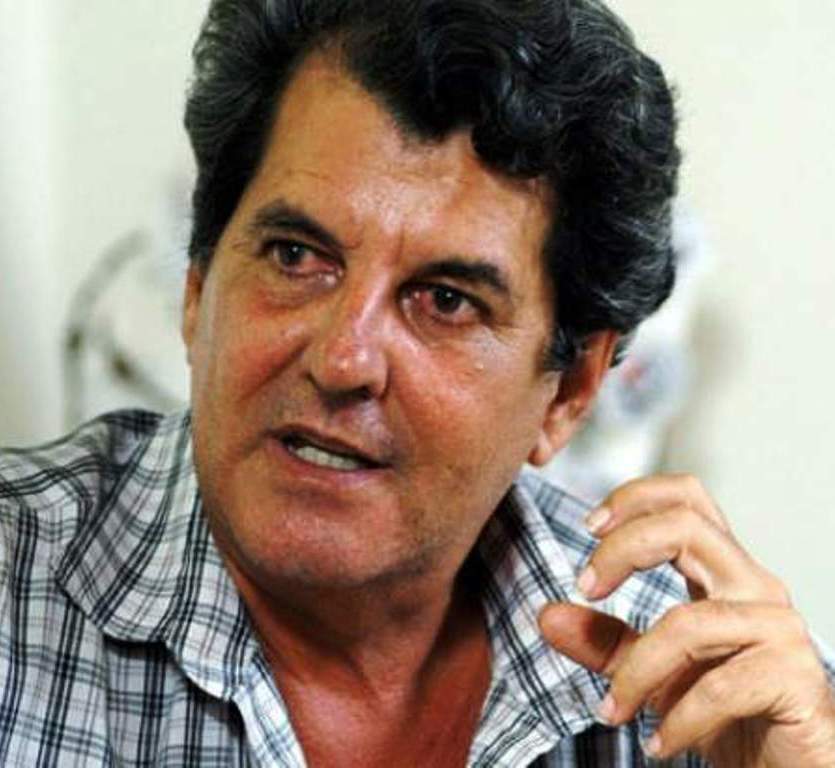

Antonio Rodiles, a physicist, has gained recognition for hosting discussions and jam sessions that are broadcast online under the name State of SATS — an activity for which he has been arrested more than once.

The middle ground, too, can be fraught. Mr. González set off a fierce debate among bloggers and intellectuals last year when, at a conference in Miami, he advocated a loyal opposition — one, he explained, that sees the government as an adversary but not as an enemy.

MR. Peters said the stance was “very practical,” adding: “They want to see great changes in their country, but they don’t want to start by tearing down the system and starting over again.”

Others disagree. “I cannot sit and debate with a government in a position of weakness, where I am not their equal,” said Walfrido López, a government critic who has been living in the United States for six months.

Mr. López said that, although he appreciated Mr. Veiga and Mr. González’s efforts, he thought they were too timid and should have a more open relationship with dissidents.

“A space is either free and open, or it’s not a space,” he said by telephone.

Mr. Veiga shrugs off such criticism. “There are people who believe that acknowledging the other is a capitulation, and you’ll find them at either end of the political spectrum,” he said. “That’s the price you pay for making some effort for the common good.”

In May, that price was to lose their space in the church. Mr. Veiga and Mr. González resigned from Lay Space, citing the polemic that they had caused within “certain sectors of the ecclesiastical community.” The two refused to comment in a telephone interview and in emails on their reasons for leaving the magazine.

The storm that ensued was a measure of their following: Bloggers and academics reacted with dismay, quibbled about whether they had jumped or been pushed, and argued about what their departure meant for civil society.

Whatever the reason, Mr. Veiga and Mr. González now hope to weave a new strand with Cuba Posible.

The fuss that erupted after he and Mr. Veiga left Lay Space took the two by surprise, he said, and convinced them that their work was worth continuing. Not that Mr. González particularly liked the attention.

“It’s nice to be stopped on the street and someone salutes you for an article you’ve written,” Mr. González said. “But, actually, we’re both pretty shy.