Tracy Wilkinson, Los Angeles Times, February 8, 2015

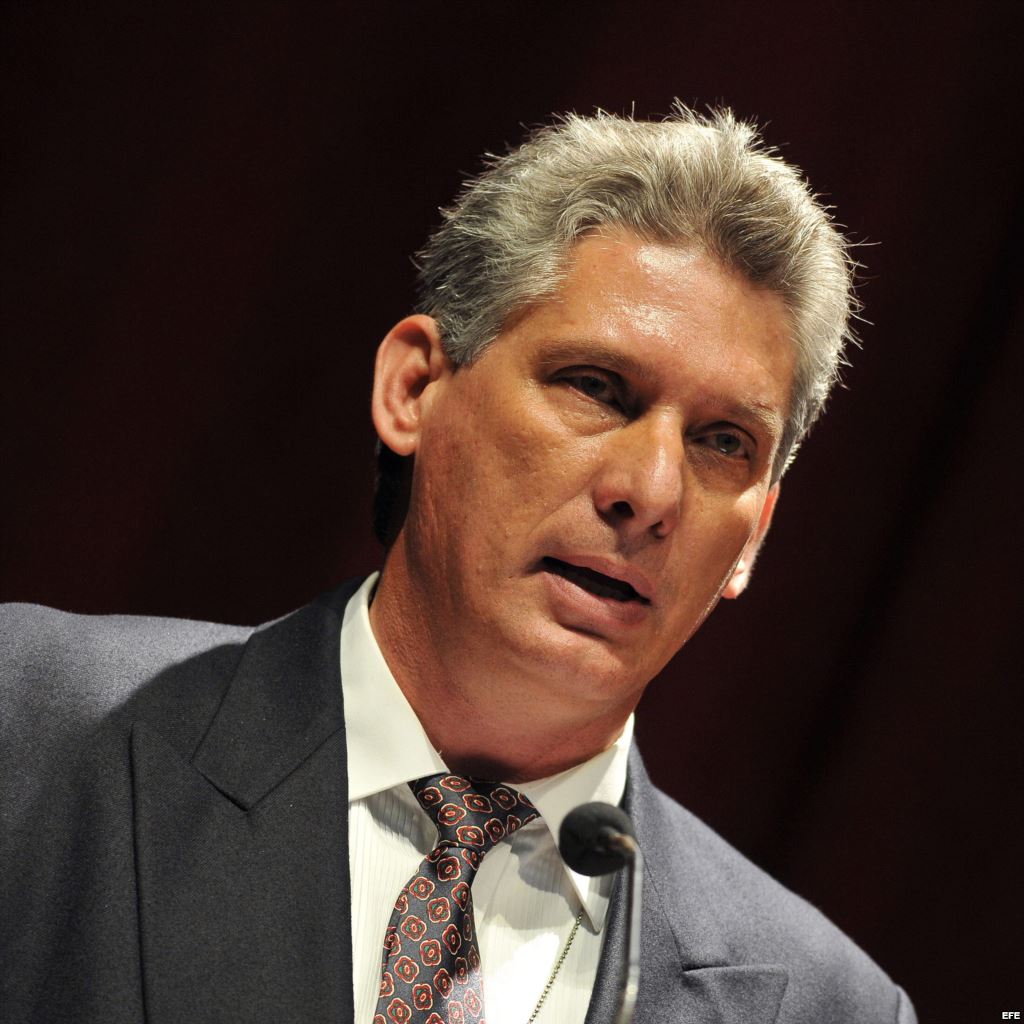

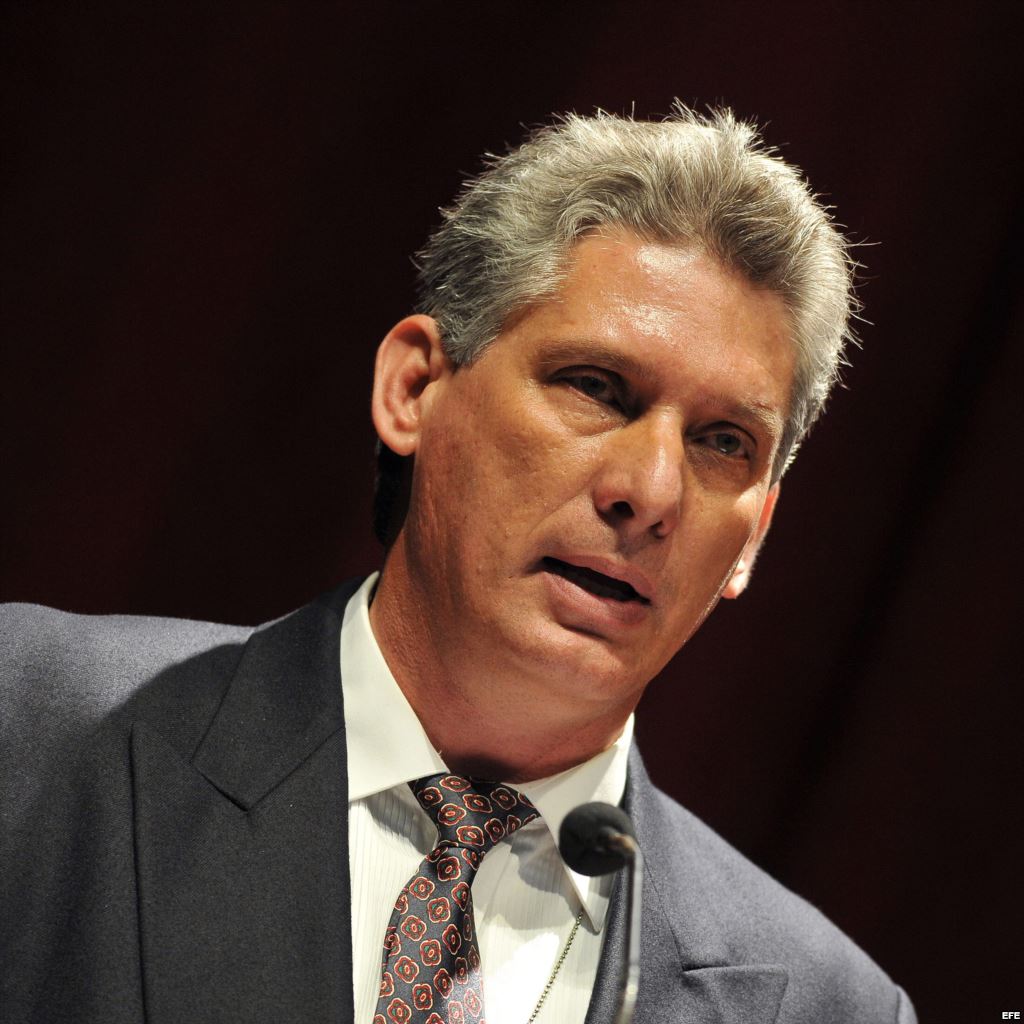

Original here: Miguel Diaz-Canel

Raul Castro and Miguel Diaz-Canel

Raul Castro and Miguel Diaz-Canel

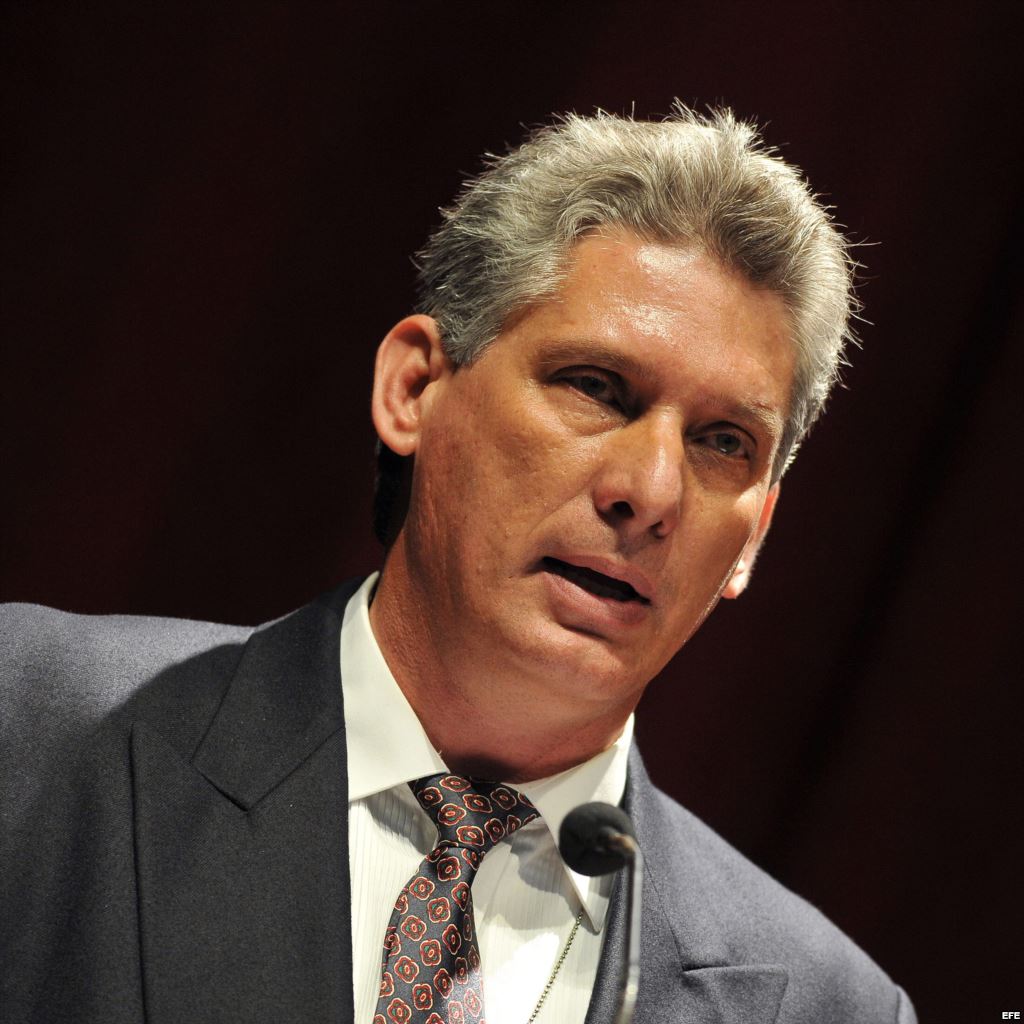

The man expected to run Cuba after Raul Castro steps down is nearly 30 years the president’s junior and is regularly on Facebook in this Internet-starved country. He is considered personable, with a certain charm, but has been careful to keep a low political profile.

Miguel Diaz-Canel’s appointment as first vice president is the most concrete signal that a generational change of leadership may hover on the horizon in Cuba, matching a demographic shift that makes the island’s population one of the youngest in the hemisphere.

Castro, 83, plucked Diaz-Canel from relative obscurity and appointed him to his new position in 2013 as he announced that he planned to leave office in 2018. That set Diaz-Canel up as heir apparent, especially after other possible candidates were unceremoniously dumped when they were secretly recorded talking about their ambitions.

That is still a no-no, and Diaz-Canel has taken pains not to steal the limelight from Castro or the president’s 88-year-old brother, Fidel, the legendary revolutionary commander and former president who has not been seen in public in months amid rumors of failing health. A new set of photographs of Fidel Castro popped up this week in official media.

The circumstances mean Diaz-Canel has yet to make much of a mark. On an island where around 80% of the population has never known a president who wasn’t named Castro, many Cubans are struggling to figure out who he is.

Asked who he thought would be the next president of Cuba, Jose Hernandez, 83, a retired farm worker in the Cuban city of Mariel, said: “It will be Raul.” Diaz-Canel, Hernandez said, “is a good negotiator who will help our community. But Raul is the president. There is nothing but Castro in our heads.”

Cuba’s younger generation is more receptive to new leadership, but many agree that whoever comes next has a herculean task to court the powerful military, restructure the economy and guide the normalization process with the United States that was announced in December.

“We’ve lived many years with a dynasty,” said Katrina Morejon, a health worker in her 20s from Havana. “People are tired of what’s happening.”

Key leaders of the army, of which Raul Castro is still the supreme commander, control several segments of the economy and will have to be carefully cultivated if Diaz-Canel is to work well with them. Diaz-Canel was born more than a year after the Cuban Revolution led by the Castro brothers ousted dictator Fulgencio Batista in 1959.

Raul Castro is expected in the final years of his government to continue with slow but important reforms in the economy, allowing a measure of free enterprise and lifting some restrictions on trade and travel. Whether it is enough as relations with the United States change will be the big test.

The goals stated by Cuba and the U.S. after decades of animosity include elevating diplomatic representations in both countries to full embassies rather than the limited “interests sections.” Handling the new relationship will put pressure on whoever is president of Cuba. Castro has made it clear that better diplomatic ties with Washington should not change Cuba’s domestic, political or economic system, nor its intolerance of dissent.

At 54, Diaz-Canel, a trained engineer with a full head of salt-and-pepper hair, is the freshest face in the highest echelons of Cuban power. He recognizes the importance of Cuba joining the Internet age, somewhat against the official grain, people who know him say. A 1982 graduate of the Marta Abreu University of Las Villas with an electrical engineering degree, Diaz-Canel essentially paid his dues, putting hard, careful work ahead of the overt ambition that has felled many an up-and-comer on the Cuban political landscape.

His work on behalf of the state has included teaching at the university level, running local governments, serving as a minister of education and holding regional Communist Party leadership posts. He was assigned management of what Cuban officials consider major areas of accomplishment by the revolution: education, sports and biotechnology. He also did an all-important stint in Nicaragua, representing the Communist Party before like-minded Sandinista leaders.

Much of his personal life has been kept private. He is thought to be married with children. Tall, with strong features, he is well-liked by Cubans in the provinces, many of whom see him as down-to-earth and accessible. His Facebook page has photographs of Diaz-Canel with workers, Raul Castro and others during visits to factories in Villa Clara and elsewhere. He is usually shown in a white guayabera, or a sports jacket and open-collar shirt. Someone has posted items calling him MDC, and at one point nominating him to run the country, saying, “MDC rocks!”

“He is well-liked, young, well-educated, and he’s gone through all the different hoops,” said Rafael Betancourt, a professor at the University of Havana. That he is admired in the often snippy world of university circles, Betancourt said, “is very significant” and shows he has talent for handling people.

It appears the Cuban leadership is gradually, gingerly trying to elevate his profile. He has been sent abroad representing Castro, especially to friendly nations like Venezuela and Laos.

It’s always a delicate balancing act, however. In a speech in Mexico in December, he managed to mention both Castros in the first three paragraphs of his comments, then quote Raul twice more.

Communist-controlled press on the island has started to run fairly regular articles about Diaz-Canel’s activities: his trip to Santiago de Cuba, his visit with workers in Santa Clara.

But there are no big billboards promoting Diaz-Canel; most such public advertising is still limited to a Castro or, especially, the five Cuban intelligence agents who were recently released from jail in the U.S., two because they finished their sentences and three as part of the deal to jump-start detente with the U.S. They are regarded as heroes in Cuba; the posters are out-of-date, still demanding freedom for the men. Diaz-Canel is nowhere to be seen.

“He is too much in the shadows of Raul,” said Arturo Lopez Levy, a former Cuban intelligence agent who knew Diaz-Canel in their hometown of Santa Clara and who now teaches in New York. “A good signal to send to the world now that things are changing would be to give him a more prominent role.”

If he were the son of a corporate boss brought into the firm, Diaz-Canel would fit the bill, having been assigned to Communist Party leadership posts in important provinces like Holguin and Villa Clara. There, people who know him say he cultivated good relationships with local military officials, some of whom have recently been promoted to key leadership posts.

His real distinction, people say, has been in social media and computer technology, an area where Cuba lags notoriously behind the rest of the world. Few Cubans have open access to the Internet, but Diaz-Canel knows its importance to any future growth in business, trade, tourism and education, analysts say.

“The development of information technology is essential to the search for new solutions to development problems” in Latin America, Diaz-Canel said in the Mexico speech. “But the digital gap is also a reality among our countries, and between our countries and other countries, which we must overcome if we want to eliminate social and economic inequalities.” Later, however, when he listed Cuba’s successes, he did not return to the theme of information technology.

“He understands that to prevent a brain drain, you have to give [Cubans] an opportunity to participate massively in the expansion of the Internet,” said an American analyst of Cuban affairs who did not want to be quoted speaking about Diaz-Canel. Whether such an expansion project is yet allowed remains unclear.

Diaz-Canel is also often praised as a hands-on problem solver, someone who could get things done at the grass-roots level and understands the politics of persuasion. He once defended a gay theater group against local officials who wanted to shut it down, earning respect among some of Cuba’s most marginalized citizens.

Diaz-Canel’s gradual ascension comes with a little-noticed, still-slight change in the Cuban political hierarchy.

Rafael Hernandez, a political commentator and editor of Temas magazine in Cuba, said conventional wisdom often holds that “the Cuban leadership is the same, you have Fidel and then Raul, and it’s more or less the same thing.” But, he says, closer examination shows a changing leadership that includes more women and Afro-Cubans, long excluded, than ever before.

That may bode well for Diaz-Canel’s future leadership, but many Cuba-watchers agree that it will ultimately be the military that calls the shots. “The military may not be a threat, but it will always be there,” Lopez Levy said. Diaz-Canel “has an arduous road to walk.”

Miguel Diaz-Canel

Miguel Diaz-Canel