A growing number of Cuban health professionals working in Venezuela are fleeing or seeking second jobs as a result of the economic and political crisis in the South American country.

By MARIO J. PENTÓN

In Cuba Today, June 22, 2016

Original Article: Cuban Doctors in Venezuela

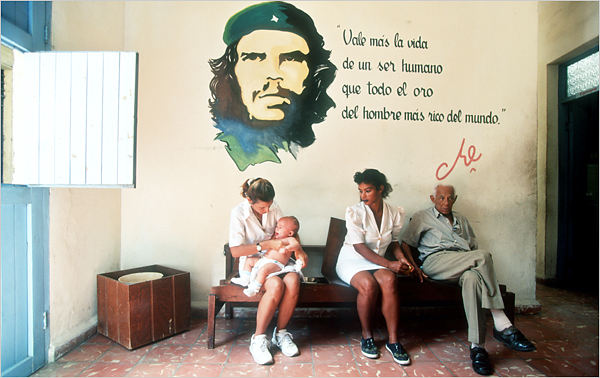

Cuban Doctors in Venezuela in More Promising Times

Tania Tamara Rodríguez never thought she would escape from the Cuban medical teams in Venezuela and become a “deserter,” now blocked by her government from returning to her country for eight years.

But the many difficulties that Cuban health professionals face in Venezuela as a result of the economic and political crisis in the South American country are leading a growing number to seek refuge in neighboring countries or obtain other jobs to make ends meet.

“Conditions for the doctors and other health professionals are horrible. You live all the time under the threat of being returned to Cuba, losing the job. You’re afraid they will take all the money – which is in Cuban government accounts – and revoke your assignment (to Venezuela) if they want to discipline you,” said Rodríguez, who now lives in Tampa.

While she worked in a medical laboratory in Venezuela as part of Cuba’s “Mission to the Neighborhood” medical aid program, the government deposited Rodríguez’s salary of 700 pesos per month (about $29) to an account in Cuba and gave her access to $280 dollars (U.S.) per month and a card for 25 percent off at the TRD shops in Cuba, which offer hard-to-find imported goods at dollar prices.

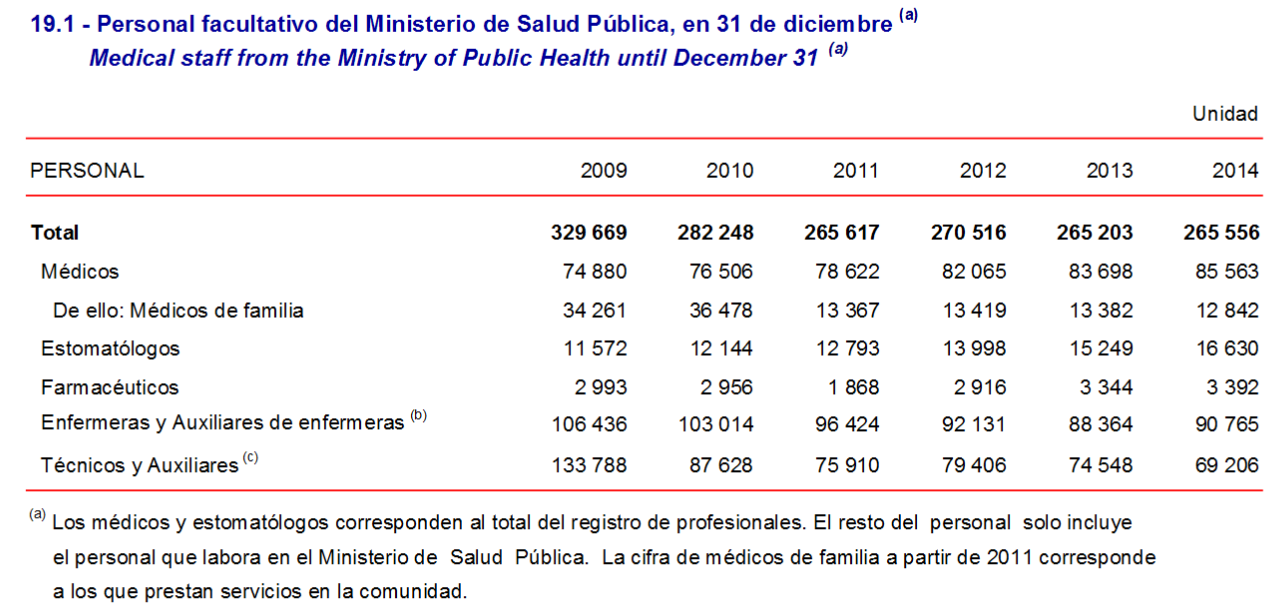

In 2014, after acknowledging that its “export of health services” was earning the island more than $8.2 billion a year, the Cuban government increased salaries in the domestic health sector. Even with the increases, which took effect after the public health sector had dismissed 109,000 employees, Cuban doctors are still not earning even close to the international median.

Rodríguez went to Venezuela in early 2015 from the eastern city of Holguín where she worked in the laboratory of the Máximo Gómez Báez. She agreed to join one of Cuba’s many medical teams in foreign countries in hopes of providing better opportunities for her 13-year-old daughter.

Cuba currently has about 28,810 medical personnel in Venezuela working in public health programs that, according to President Nicolás Maduro, represent a priority sector for his government and has cost Venezuela more than $250 billion since 1999.

The payment arrangement, essentially trading Venezuelan oil for Cuban medical personnel, has been repeatedly denounced by critics as a way for the Venezuelan government to cover up its subsidies to Cuba. Cuba then resells part of the refined oil products on the international market.

Rodríguez, who arrived in the United States after a few months in Venezuela under the U.S. government’s special parole program for Cuban medical personnel who defect, saved the money needed to buy her daughter a plane ticket to the United States from Cuba. But when her family took the girl to an Interior Ministry office to apply for a passport, she was denied because the mother was still listed as working in Venezuela.

“I don’t understand how I can be listed as working when I have been in the United States for more than a year. Someone must be pocketing the money the Venezuelan government is paying for me,” Rodríguez said.

According to the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Service (USCIS) agency, 2,335 petitions were received in Fiscal Year 2015 under the Cuban Medical Professional Parole (CMPP) program, an initiative by the George W. Bush administration that offers visas to Cuban medical personnel “recruited by the (Cuban) government to study or work in a third country. Since its start in 2006, more than 8,000 medical professionals have been admitted under the program. Solidarity Without Borders, a Hialeah non-profit that helps the arriving Cuban medical professionals, told el Nuevo Herald that the number of Cubans applying for the CMPP has risen in recent years. Not everyone is accepted, and 367 were rejected in fiscal year 2015, according to official data.

Rodríguez said that when she arrived in Venezuela in 2015, she was assigned to work with other Cuban medical personnel in the north central state of Falcon.

“Everything in Venezuela is a lie,” she complained. “We were forced to throw away the reactive for CKMB (a type of blood test), a product that is scarce in Cuba. But we had to throw it away so that it would be marked in the books as having been used and Cuba could sell more. The same happened with the alcohol, bandage, medicines … “Everything was produced in Cuba and paid for by the Venezuelan government,” Rodríguez said. “We faked lists of patients and were forced to live on nothing, while Cuba took all the money.”

During the time she worked in Venezuela, Cuban officials paid each medical professional about 3,000 bolivares (about $3) per month — an amount that has increased substantially recently because of an inflationary crisis and the relentless devaluation of the Venezuelan currency.

“Sometimes I had to do little jobs on the side to make ends meet,” she said. “Thank God that many Venezuelans take pity on the Cubans and help us.” “Maybe what happened in my case was that when I decided to escape, I went to the municipality and told them everything about the disaster” at her clinic, she said. “And now they want to take revenge because I denounced them.”

Another Cuban doctor who works in the northeastern state of Anzoategui spoke on the condition of not being identified because of fear of being punished for speaking with a journalist.

“We started earning 3,000 bolivares and we’re now up to 15,000,” he said, or about $15 on the black market. “What’s interesting is that it makes no difference if they give us more bolivares because they are worthless in real life.” “Our working conditions are horrible. We are salaried slaves of Cuba,” the doctor said. “They keep us in groups. Since I arrived, I live with three doctors from other parts of the island, so I have to share my room with someone I don’t know, and every day at 6 p.m. I have to ‘report’ that I am home.”

Officials of the Cuban medical teams in Venezuela justify the daily check-ins as a security measure due to the high levels of violence in the neighborhoods where they work. The doctors, however, see it as part of an effort to keep a close watch on them.

“There are many (Cuban) state security agents. Their job is to keep us from escaping,” said the doctor working in Anzoategui. “When you arrive in Venezuela, they ask you if you have relatives abroad, especially in the United States. We all say no, even if we do, because the surveillance is even worse then.”

The economy in Venezuela is so poor, he added, that returning from his last vacation in Cuba he had to carry back laundry and bathroom soap and toothpaste.

“When we first got here, this was paradise. They had everything we did not have in Cuba. Today it’s exactly the opposite,” he said. “We came thinking we would help our families, and it turns out they are the ones helping us. If it were not for the money that my brother in Miami sends me, I don’t know what I would do.”

Several other medical professionals in Venezuela also said that authorities try to hide cases when the Cubans become the victims of crimes, even when they are killed.

“You can’t avoid being robbed, because everyone gets robbed here. A stray bullet, a thug who doesn’t like you, we run all those risks,” said another Cuban doctor who also asked for anonymity. “One day I was mugged by two children, no more than 12 years old. I had to give them all my money because the pistols they were playing with were real.”

The personal relations of the Cuban medical personnel are also watched.

“They warn you that it can go badly for you if you have relations with Venezuelan government critics,” the female doctor said. And although intimate relations with Venezuelans are formally forbidden, “people find a way.”

During the 13 years that Cuba has been sending medical personnel to Venezuela, more than 124,000 have served in the South American country. Thousands have escaped to the United States and other countries, searching for better lives.

For many years, like Rodríguez, the medical defectors were banned from returning to Cuba for eight years. Last year, Cuba announced the defectors could return and would be guaranteed “a job similar to what they had before.”

But there was a catch: Those who returned would need a special permit to travel abroad again.