The Author: Sarah Stephens of the Center for Democracy in the Americas has just published a study on gender equity in Cuba.

The complete report is available for download CDA_Womens_Work[1] The first part of the Executive Summary is presented below.

Ritter’s comment:

While this is an interesting study, the author seems to studiously avoid even the mention of some of the most courageous women in Cuba who are already having an influence on public policy and will likely play a more important role in building Cuba’s future than any of the women cited or interviewed for the study. I am referring of course to the independent journalists, pro-democracy activists, and those who dare to speak up in support of the genuine respect for the basic human rights that Cuba has signed on to in the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

How could an organization labelled the Center for Democracy in the Americas not have spoken to individuals such as Yoani Sanchez, Miriam Celaya, the Ladies in White, or Miriam Leiva?

The immigration reform law would not likely have been passed at this time were it not for the unrelenting pressure of Yoani Sanchez and the international publicity this engendered and the shame the travel restrictions brought on the Cuban government.

Arch Ritter

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

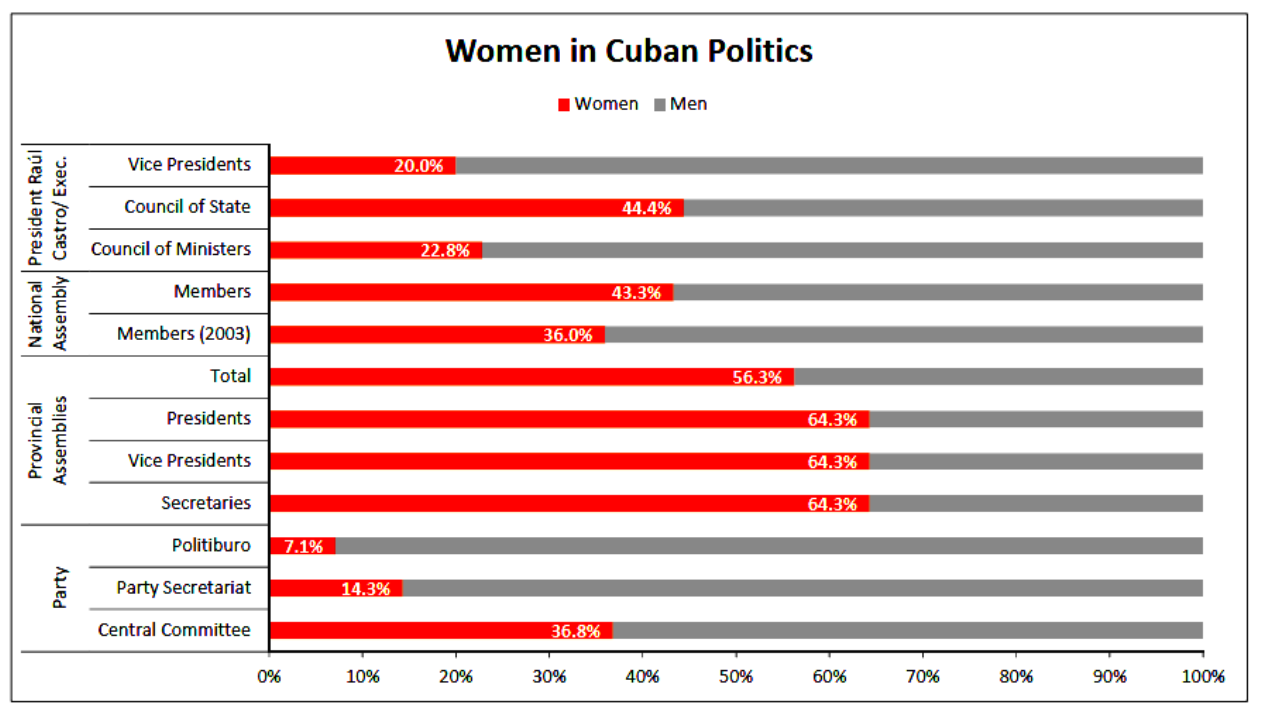

“Women’s Work: Gender Equality in Cuba and the Role of Women Building Cuba’s Future,” a report by the Center for Democracy in the Americas, examines progress made by Cuban women toward gender equality since the 1950s and discusses how that progress can be sustained in the future.

Cuba is highly ranked by international organizations from Save the Children to the World Economic Forum for the health and well being of its mothers and children; the literacy and educational attainment of its population; and for meeting or progressing toward the Millennium Development Goals.

These accomplishments are met with skepticism even disbelief by some in the U.S., because Cuba has a tiny economy, it is not capitalist or rich and, by U.S. standards, it is not free. Yet, the numbers speak for themselves.

But, the data also demonstrate, and many Cuban women agree, that measured against key objectives of gender equality – do women have access to higher-paying jobs; can they achieve a fair division of labor at work and home; are they acceding to positions of real power in the communist party or government– Cuba has a long way to go.

Now, as Cuba faces an economic crisis driven by fiscal, competitive, and demographic pressures, the government is trying to update its economic model. But, several actions – such as cutting budgets and controlling costs in its public health and education systems, and shrinking state employment rolls and moving workers into private sector jobs – could put Cuba’s gender equality achievements at considerable risk. Many Cuban women are reluctant to make the transition from the state jobs where they found work and received benefits to private sector employment, because they lack training, job security and benefits, and access to capital.

With ample global evidence that broadening rather than constraining participation by women increases economic growth, social wellbeing, and family formation, Cuba can improve its prospects for addressing the crisis by preserving, and indeed, expanding its commitment to gender equality. Cuban women also want to expand their roles, their power, and their ability to participate in the building of Cuba’s future.

CDA believes it would serve the national and humanitarian interests of the U.S. to help Cuban women achieve greater economic success as their nation undergoes a stressful adjustment to a new economic model, and the report offers recommendations for doing so.