Pavel Vidal

Profesor de la Universidad Javeriana Cali

Se requiere más tiempo para que se estabilicen los nuevos equilibrios y la economía reaccione con energía a los nuevas señales e incentivos. Con reformas estructurales complementarias se pueden acortar estos tiempos y potenciar la reacción.

March 04, 2021

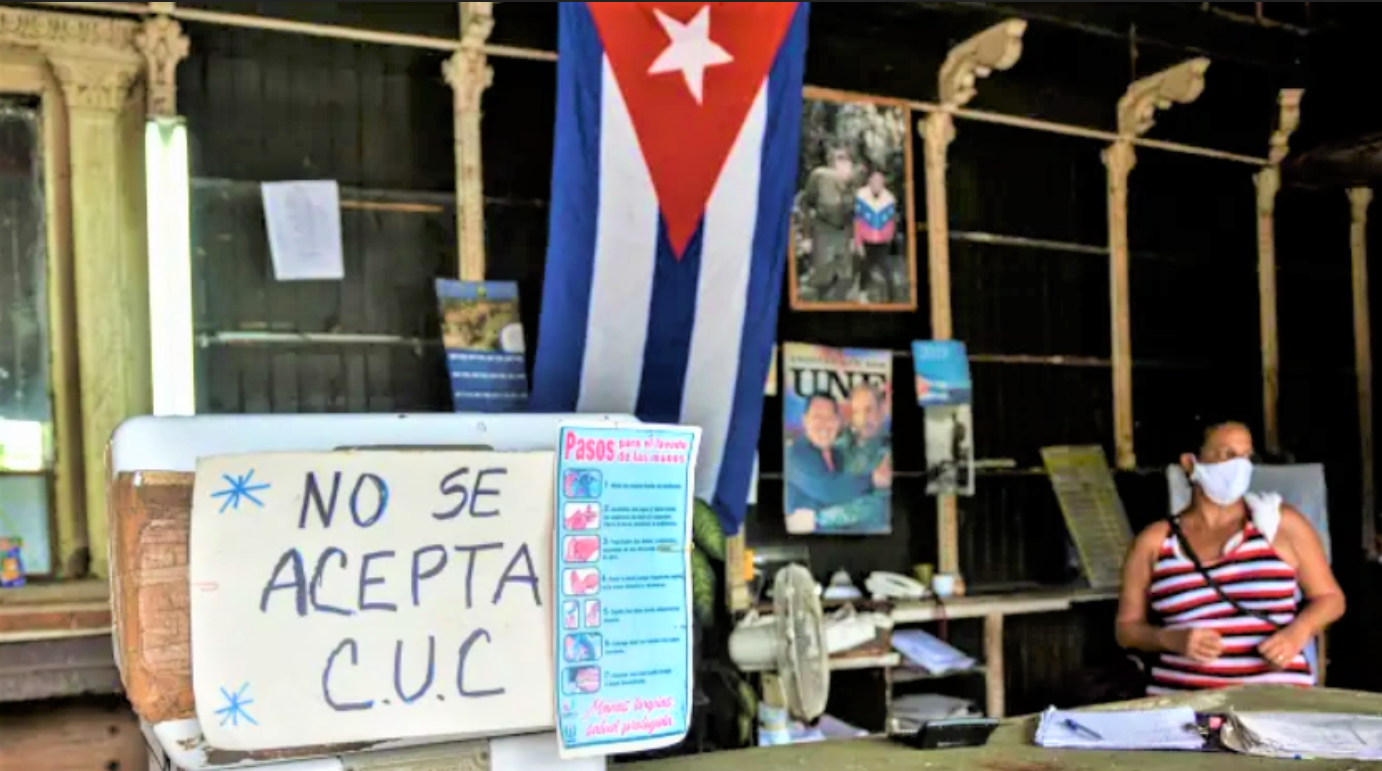

No debería sorprender el remezón que la devaluación del peso cubano y salida del CUC están provocando en

- los costos de producción,

- los precios mayoristas,

- el valor de la canasta básica,

- las tarifas eléctricas y los precios de los mercados agropecuarios,

- de trabajadores por cuenta propia y

- de todo tipo de transacciones en los mercados informales.

No debería ser motivo de asombro, aunque sí de mucho análisis, que esté cambiando radicalmente la realidad financiera de empresas estatales, cooperativas, negocios privados y hogares. Se trata de una devaluación de 24 veces de la tasa de cambio oficial y de alrededor de 10 veces de la tasa de cambio promedio en la economía,[1] una de las mayores en la historia de tipos de cambio múltiples en América Latina.

Durante mucho tiempo los economistas explicamos que la unificación monetaria constituiría un choque financiero inmediato con múltiples beneficios, pero que en su mayoría se materializarían gradualmente en el mediano y largo plazo. Nunca se ocultó que era un trago amargo para el sistema productivo, pero que había que tomarlo porque es imposible desarrollar una economía con dos monedas nacionales y múltiples tipos de cambio.

Con estas distorsiones monetarias llevábamos casi tres décadas completas midiendo mal los hechos económicos, sobrevalorando o subvalorando costos de producción, salarios, retornos y riesgos financieros, deudas y activos financieros, minimizando el valor de muchas buenas decisiones económicas y ocultando el costo de un montón de malas decisiones y reformas pospuestas. No todo lo que hicimos antes de 2021 estuvo mal calculado, pero sí una gran parte.

La unificación monetaria representa un choque financiero que produce cambios en los precios relativos a una velocidad mucho mayor que la capacidad de respuesta promedio del sistema productivo. Durante un tiempo las unidades económicas quedan atrapadas en el medio, gran parte de lo que venían haciendo ya no tiene sentido económico, pero todavía no logran entender todo lo nuevo que deben hacer, y cuando comienzan a comprenderlo no tienen la forma de reaccionar en la proporción que necesitan. En correspondencia, las políticas económicas necesitarían trabajar en dos aspectos fundamentales para mermar el impacto de corto plazo del choque financiero: minimizar la incertidumbre y aumentar la capacidad de reacción de las unidades económicas.

El éxito de la reforma monetaria no está garantizado por el solo hecho que la unificación de las monedas y las tasas de cambio oficiales eliminan distorsiones.

En estos dos frentes hay muchas cosas que el propio diseño inicial de la “tarea ordenamiento” ya tiene incorporado, y hay muchas otras que se podrían añadir. El diálogo permanente de las autoridades económicas con los empresarios estatales, agricultores, emprendedores privados, empresarios extranjeros y gobiernos locales será una fuente de información fundamental para corregir y negociar lo que no se previó. Para aumentar la capacidad de respuesta son varias las reformas estructurales que se deben ir acometiendo. En este caso hay recomendaciones elaboradas por economistas como Pedro Monreal, Ileana Díaz, Mauricio de Miranda, Carmelo Mesa-Lago, Omar Everleny, Oscar Fernández, Juan Triana y Ricardo Torres, entre otros.

Es importante subrayar que el éxito de la reforma monetaria no está garantizado por el solo hecho que la unificación de las monedas y las tasas de cambio oficiales eliminan distorsiones. La política económica no puede achantarse y esperar a que se vayan materializando los beneficios de mediano y largo plazo. Tampoco puede caer en la complacencia de publicitar algunos de los beneficios puntuales que se pueden apreciar en el corto plazo, tales como más personas buscando trabajos formales o determinados ahorros en el consumo de los hogares. Son buenas señales y constituyen los primeros ejemplos de lo que se puede lograr con un cambio en los incentivos económicos, pero distan mucho del cambio estructural y el salto de eficiencia que podría derivarse de la “tarea ordenamiento”, que evidencie que valió la pena asumir el riesgo de devaluar 10 veces la moneda en un solo día.

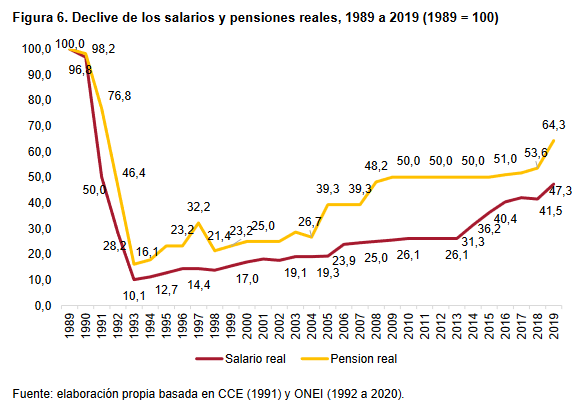

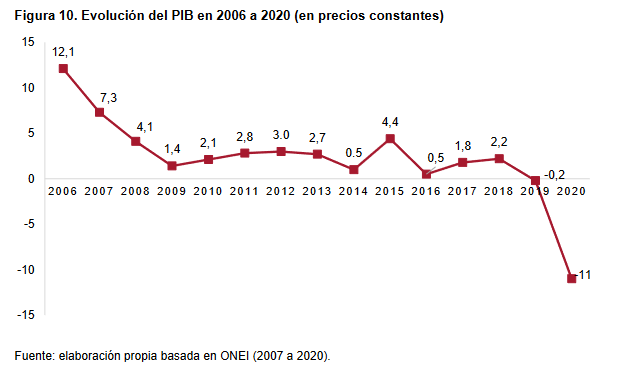

El gobierno tampoco debería prometer y forzar unos beneficios irrealizables de corto plazo, especialmente en lo que tiene que ver con el aumento del poder adquisitivo de los salarios y las pensiones. Las proyecciones contrafactuales siempre son muy especulativas, pero podría decirse que en un escenario hipotético sin pandemia y sin una caída del 11% del PIB, tal vez sí se hubiese podido lograr algún aumento de los salarios y pensiones reales a partir de la redistribución de riqueza e ingresos y de un cambio en la estructura del gasto público. Esta era el escenario de la reforma monetaria en el papel, pero la realidad de 2020 y 2021 ya sabemos que es otra muy diferente.

Pretender que este aumento nominal de ingresos se vaya a traducir en mejoras reales en el contexto actual no es realista.

Entiendo que la manera en que el equipo económico técnico logró “vender” políticamente la “tarea ordenamiento” fue combinando la devaluación de la tasa de cambio con el aumento de salarios y pensiones. Sin embargo, pretender que este aumento nominal de ingresos se vaya a traducir en mejoras reales en el contexto actual no es realista, genera falsas expectativas y promueve incentivos perversos en los entes reguladores y políticos. En un reciente panel en la Asociación de Estudios Cubanos (ASCE) presenté una estimación que apunta a una probable caída de alrededor del 15% del salario promedio real en el sector estatal en 2021. De lograrse en el complejo escenario económico y financiero actual, esto debería apreciarse como un gran logro.[2]

Para esclarecer mi posición, creo que fue acertado combinar ambas acciones de política económica, incluso (y especialmente) en el escenario de 2021. El aumento nominal de salarios y pensiones permite proteger a un grupo grande de hogares de los costos sociales de la devaluación. Pero es diferente presentar el aumento salarial y de pensiones como una protección, a prometer un incremento de los ingresos reales en medio de un ajuste tremendo de la tasa de cambio y de los precios relativos, en una economía que ha visto reducida prácticamente a cero una de sus principales fuentes de ingresos externos por la caída internacional del turismo.

Es este mismo panel en ASCE expuse una proyección de inflación que ubica la tasa más probable para este año alrededor de 500%. Cerca del 300% de la inflación se debería al efecto traspaso, es decir, al impacto de la devaluación de la tasa de cambio sobre los precios. El otro 200% se explicaría principalmente por el exceso de demanda, es decir, el aumento de salario por encima de la productividad. Y es importante anotar que en este escenario ya se reconoce el esfuerzo del gobierno para intervenir administrativamente y controlar el efecto traspaso, tomando en consideración los límites que ha colocado el Ministerio de Finanzas a los precios mayoristas empresariales y los subsidios que se mantienen. En este escenario de inflación de 500% se asume que con estas regulaciones el gobierno podría llevar el traspaso al valor medio que se observa en las economías en desarrollo, según las estimaciones del Banco Mundial.[3] De hecho, si no se considera el efecto de estas regulaciones del Ministerio de Finanzas, la inflación superaría los 900% y el salario real caería un 50%.

Bajo estos cálculos, tanto el objetivo oficial de aumento de los precios promedios en solo 1,4 veces, como el objetivo de aumento del poder adquisitivo de salarios y pensiones parecen inalcanzables este año. Estimular a los entes reguladores y políticos a reprimir la inflación más allá de lo que es posible va a provocar más daño que beneficio, y puede llevar a destruir los mismos resortes que se necesita para la recuperación. Una vez más podemos recordar el fracaso en obtener los 10 millones de la zafra de 1970 y el desgaste que representó concentrar los esfuerzos en un objetivo inalcanzable.

Se puede reconocer la necesidad de regular …los precios de las empresas estatales y de otros mercados donde primen estructuras monopólicas, pero es un error imponer precios donde existen mercados que pueden cumplir esta función sin intervención estatal.

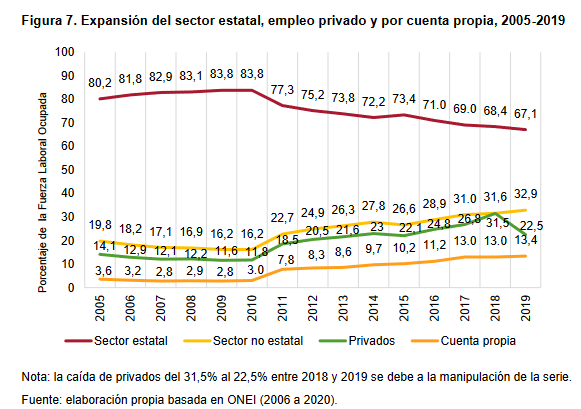

En una economía más descentralizada, con un número mayor de actores económicos y mercados más abiertos y competitivos, la mayor parte de las correcciones de precios relativos podrían confiarse a las interacciones y contrapesos del sistema productivo, pero dada la estructura monopólica y cerrada de donde parte el ajuste monetario cubano, la negociación y la corrección sistemática de los controles de precios es la única vía para compensar parcialmente la rigidez e ineficiencia inherente a la fijación centralizada de los precios. Se puede reconocer la necesidad de regular mediante medidas administrativas los precios de las empresas estatales y de otros mercados donde primen estructuras monopólicas, pero es un error imponer precios donde existen mercados que pueden cumplir esta función sin intervención estatal.

El éxito de la “tarea ordenamiento” no puede medirse a partir de los indicadores de 2021. La tasa de cambio y los precios se han movido en una mejor dirección, pero con una alta velocidad y en un complejo contexto. Se requiere más tiempo para que se estabilicen los nuevos equilibrios y la economía reaccione con energía a los nuevas señales e incentivos. Con reformas estructurales complementarias se pueden acortar estos tiempos y potenciar la reacción.

[1] Tomando en cuenta que la población y el sector privado operaban desde antes con la tasa 24 pesos por dólar, y que en 2021 el mercado paralelo refleja una tasa de 50 pesos por dólar.

[2] Ver panel junto con Ricardo Torres y Carmelo Mesa-Lago en la Asociación de Estudios Cubanos (ASCE) el 16 de febrero de 2021

[3] Banco Mundial: “Special Topic. Exchange Rate Pass-Through and Inflation Trends in Developing Countries” Global Economic Prospects, junio de 2014.