By Arch Ritter October 7, 2013

On December 11, 2012, a battery of new laws and regulations on non-agricultural cooperatives was published in Cuba’s Gaceta Oficial, No. 53, including two Council of State Decree-Laws, two Ministerial Resolutions, one Council of Ministers Decree, and one Ministerial “Norma Específica de Contabilidad.” This legislation outlined the framework for the structure, functioning, governance and financial organization of the new cooperatives and provided the legal framework within which they were to operate.

This major institutional reform may revolutionize the structure and perhaps the functioning of the Cuban economy. It also may have political implications as the cooperatives are to be governed with a form of workers’ management. The legislation presented the cooperatives as “experimental,” and indicated that after some 200 were initially approved, the institutional form would be reappraised and modified. There is thus some uncertainty regarding the long-term character of the legislative framework governing the structure and functioning of the cooperatives.

The establishment of an apparently democratic form of workers’ ownership and control is interesting, surprising and perhaps paradoxical, since Cuba’s political system is characterized by a highly centralized one-party monopoly in which political participation is manipulated effectively from above. Elections in Cuba’s one-party system are a transparent charade and an insult to Cuban citizens.

COOPERATIVE GOVERNANCE

The new regime for non-agricultural cooperatives provides for ownership and management of the enterprise by its employees, with mainly independent control over the setting of prices, the purchase of inputs, decisions regarding what to produce, labor relations and the remuneration of members through wages and the distribution of coop profits.

The ultimate authority within any single cooperative will be its General Assembly which would include all its members. This body would be empowered to elect a president, a substitute and a secretary by secret ballot (Decree-Law 305, Article 18.1). The specific managerial structure of the enterprise is to be determined by the complexity and size of the cooperative and the number of members. Cooperatives with fewer than 20 members would elect an “Administrator.” Those with 20 to 60 members would elect an “Administrative Council.” Those with more than 60 members would elect a “Directive Committee” as well as an “Administrative Council.” The cooperative’s financial management will also depend on its size and complexity, and would be the responsibility of a single member for a very small cooperative enterprise or a financial committee for a large coop. The management structures and functioning are delineated in detail in Decree 309 of the Council of Ministers.

SOME ADVANTAGES OF COOPERATIVES

The new cooperative enterprise involves democracy in the work-place, a major improvement over both state enterprise and privately-owned enterprise, in the view of many observers.

Under the Cuba’s traditional state enterprise system, workers have been “order takers.” Their labor unions have served as conveyor belts for orders from the top to the workers at the bottom. Rather than defending the interests of their membership, the main purpose of Cuba’s unions has been to ensure that the interests of the nation – as determined by its political leadership – are implemented through the unions. In a private enterprise in most market economies, the worker is also an “order taker,” but may or may not have a strong labor union to defend his or her interests.

It is instructive to recall here that the governmental announcement of September 2010 presenting the proposal for the lay-off of some 500,000 workers in the public sector of the economy by March 2011– to be reabsorbed in the self-employment or micro-enterprise sector – was made in a “Pronunciamiento” from the head of the Central de Trabajadores de Cuba (CTC), Cuba’s official labor union confederation and published in Granma. It is hard to imagine the head of any other national union confederation making such a proposal on behalf of the relevant government.

On the other hand, within the cooperatives, the members should be in substantial control through the governing mechanisms that the legislation noted above creates. The system would in fact be a form of workers’ management of the sort that we have not seen since the days of Tito in Yugoslavia.

It perhaps should be noted that most so-called “capitalist…” or “mixed market economies” have significant cooperative sectors. For example, Brazil has 6,652 coops with 300,000 employees; Canada has 9,000 coops with around 150,000 employees; the United States has 30,000 coops employing over 2 million people; and France has 21,000 coops employing 3.5% of the labor force (International Cooperative Alliance.)

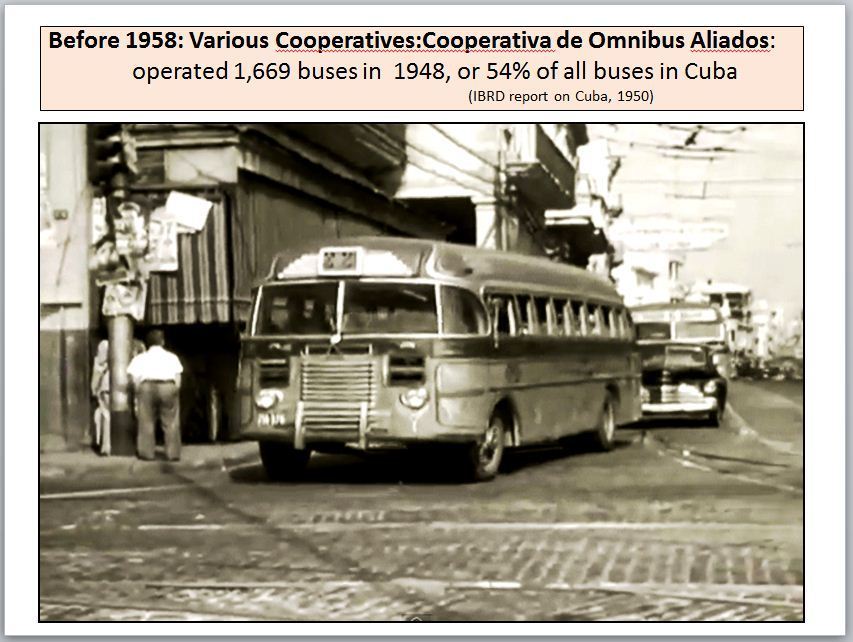

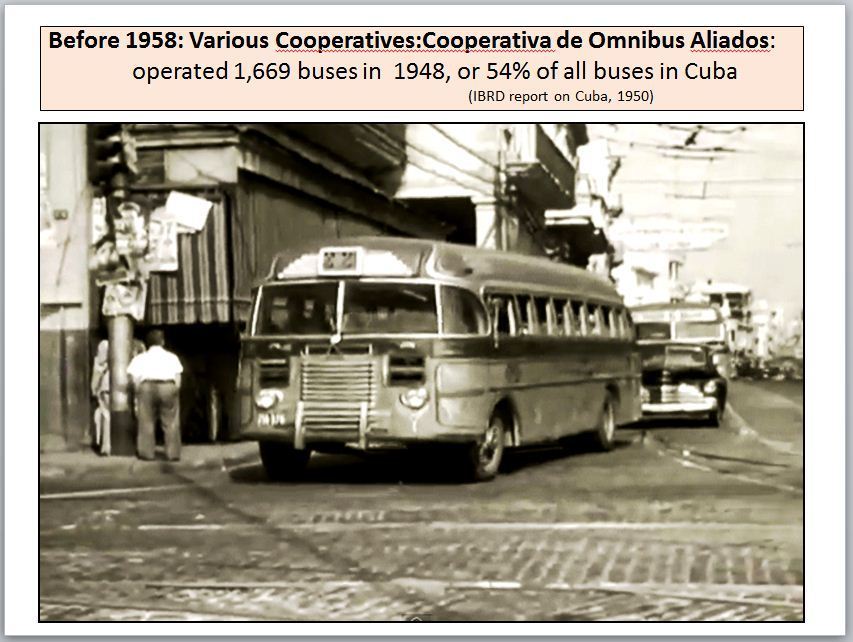

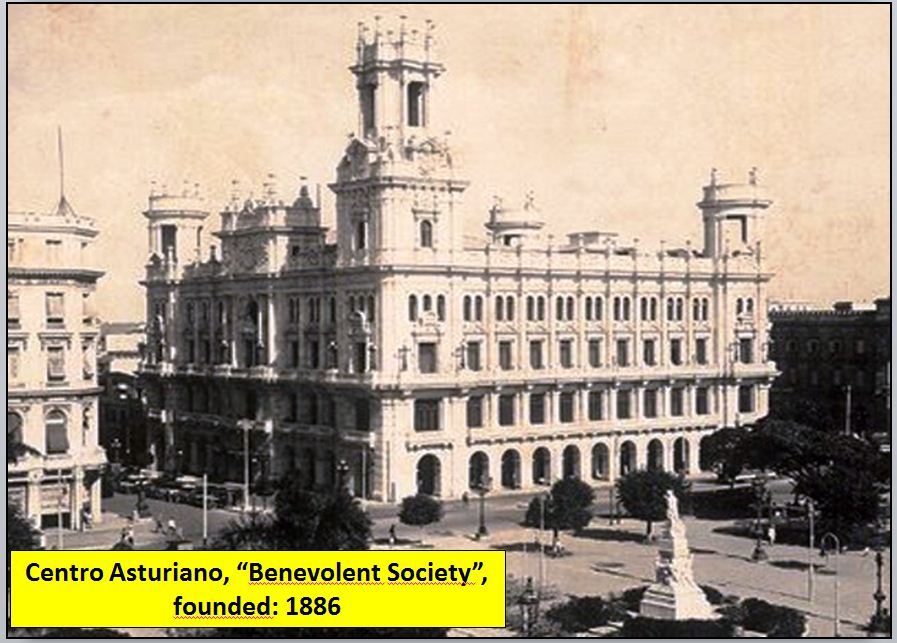

Moreover, Cuba had a significant cooperative sector before 1959, including some major “Benevolent Societies” and the Cooperativa de OmnibusAliados.

Democratic control of economic enterprises is an end in itself, but it also strengthens worker commitment to a shared endeavor thereby improving the intensity, dedication and effectiveness of workers’ efforts.

Thus, greater democracy in the work place should result in improved productivity. If Cuban cooperatives are genuinely democratic, they may function more efficiently and effectively than both state enterprise and privately-owned enterprise.

WILL THE COOPERATIVES BE DEMOCRATIC?

Will Cuba’s non-agricultural cooperatives in fact be authentically democratic? So far, it is too soon to say as the first cooperatives began operation only in July 2013. As noted earlier, the governing legislation will be modified in the light of the operational experience of the first cooperatives.

Governance may be a continuing problem for cooperative enterprises. The “transactions costs” of participatory management may be significant. Personal animosities, ideological or political differences, participatory failures, and/or managerial mistakes can all serve to weaken the decision-making process and to generate dysfunction. Of course this also happens with private enterprises as well as state enterprises

Secondly, the new cooperatives must go through a complex approval process before they can come into existence. They must be approved initially by the municipal “Organs of Popular Power,” then by the “Permanent Commission for Implementation and Development of the Guidelines,” and ultimately by the Council of Ministers. Will this be a reasonably automatic process or will political controls be exerted to determine which cooperatives can come into existence? One can imagine efforts at the highest political levels to approve favored cooperatives or cooperatives in particular areas of the economy and thereby to shape the evolution of the sector in accordance with preconceived official ideas, as opposed to letting the sector evolve spontaneously and naturally. With such controls on the approval process, the emergence of the cooperative sector could be deformed and stunted.

On the other hand, conceivably the approval process will be less controlling and permit all feasible proposals to be attempted. The Chief of the Management Model Sectionof the “Permanent Commission” assured journalists that this process would be “open” (Juventud Rebelde, 2012). But in the same article, he stated that some cooperatives would be established “according to the interests of the state” (Ibid). If this is the case, the principle of voluntary membership could be jeopardized. Cooperatives established in this manner would resemble those in agriculture that were imposed from above, with negative consequences in terms of both worker commitment and the effectiveness of the incentive system in the cooperative.

Thirdly, what will be the role of the Communist Party in the new cooperatives? If the control of the general assemblies of medium and large-sized cooperatives is captured by nuclei from the Party, not only would workers’ democracy be subverted, but incentives to work seriously would likely be diminished. Will the Party keep out of cooperative enterprise management?

If authentic democracy were to emerge within the cooperatives, would this have a spread effect into the political system? Conceivably. But Cuba’s agricultural cooperatives have had little or no democratizing effects on the political system – although these cooperatives have not been genuinely democratic either. The “UBPCs” or Unidades Básicas de Producción Cooperativa were in reality state enterprises. This was acknowleged by the government of Cuba when it instituted a series of reforms in the management of the UBPCs aimed at converting them into more genuine cooperatives. (Granma, 2012)

Possible democratic spread effects from the cooperatives to the political system do not seem to be of concern for the government of Raúl Castro.

CONCLUSION

If this initiative to establish non-agricultural cooperatives is implemented broadly in the Cuban economy, it could constitute a change and perhaps an improvement of historic dimension. With much of the state sector of the economy converted to cooperative institutional forms, Cuba could become a country of “cooperative socialism,” with a state sector, a cooperative sector, a joint foreign/state enterprise sector, and a micro-enterprise sector. This would be quite different from the highly centralized and state-owned system to which Cuba aspired for half a century. Cuba’s economic system would also continue to be unique in the world and to be of consuming interest to observers, analysts and those looking for alternatives on the left to the world’s prevailing “mixed market economies

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Decree 309, Council of Ministers. Gaceta Oficial de la República de Cuba, Número 53. 11 de diciembre de 2012.

Decree-Law 305. “De las cooperativas no agropecuarias.” Gaceta Oficial de la República de Cuba, Número 53. 11 de diciembre de 2012.

Granma. September 11 and 14, 2012.

International Cooperative Alliance. WebSite: www.ica.coop (accessed January 15, 2013).

Juventud Rebelde. 18 de diciembre de 2012. “Debate sobre la nueva ley de cooperativismo : Se buscan socios.” http://www.cubainformacion.tv/index.php/economia/47243–cuba-extiende-las-cooperativas-a-a-la-traduccion-la-informatica-y-la-contabilidad. Accessed January 16, 2013.

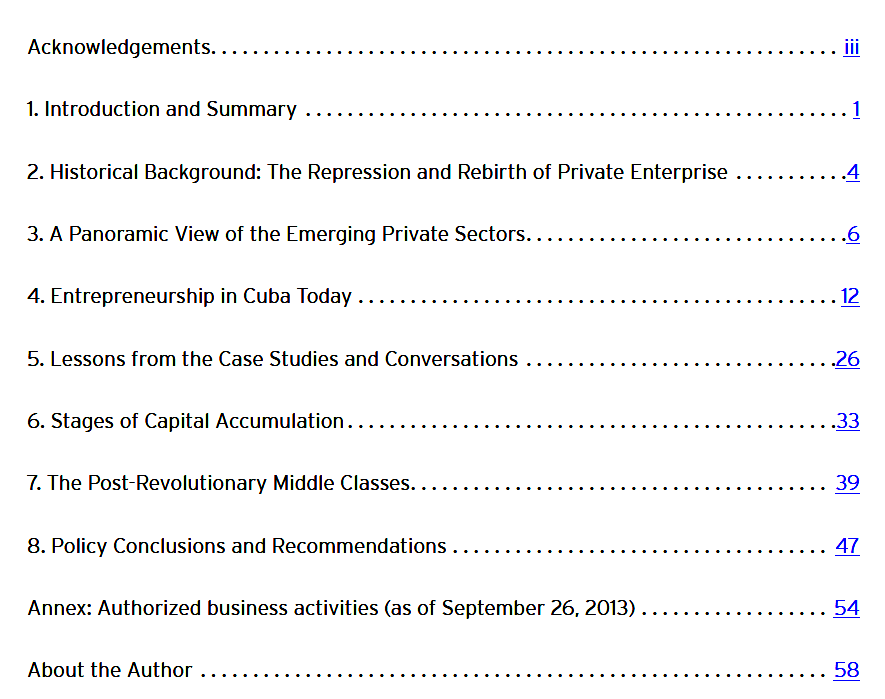

John Paul Rathbone; also author of . “The Sugar King of Havana: The Rise and Fall of Julio Lobo, Cuba’s Last Tycoon”

John Paul Rathbone; also author of . “The Sugar King of Havana: The Rise and Fall of Julio Lobo, Cuba’s Last Tycoon”