By Mark Frank, Havana — Reuters, Globe and Mail, May 15, 2013

Canadian and British executives of three foreign businesses shut in 2011 by Cuban authorities, ostensibly for corrupt practices, have been charged after more than a year in custody and are expected to go on trial soon, sources close to the cases told Reuters.

The arrests, part of a broad government campaign to stamp out corruption, sent shock-waves through Cuba’s small foreign business community where the companies were among the most visible players.

Until then, expulsions rather than imprisonment had been the norm for those accused of corrupt practices.

The charges against the executives involve various economic crimes and operating beyond the limits of their business licenses on the communist-run island, according to the sources, who asked to remain anonymous and who include a close relative of one of the defendants. Some of the foreigners are alleged to have paid bribes to officials in exchange for business opportunities.

Dozens of Cuban state purchasers and officials, including deputy ministers, already have been arrested and convicted in the investigation into the Cuban imports business that ensued.

Cuba has mounted a crackdown on corruption in recent years as part of a gradual reform process to open up the state-run economy to greater private sector activity. Under Cuban law, trials must begin within a month of charges being filed, though small delays are common and postponement can be sought by the defendants’ lawyers.

“There is definitely movement and the trials could begin soon,” a Western diplomat said.

The crackdown began in July 2011 with the closure of Canadian trading firm Tri-Star Caribbean and the arrest of its chief executive, Sarkis Yacoubian.

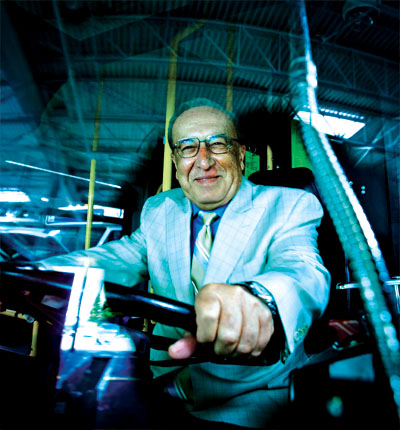

In September 2011, one of the most important Western trading firms in Cuba, Canada-based Tokmakjian Group, was also shut and its head, Cy Tokmakjian, taken into custody.

In October 2011, police closed the Havana offices of the British investment and trading firm Coral Capital Group Ltd and arrested chief executive Amado Fakhre, a Lebanese-born British citizen. Coral Capital’s chief operating officer, British citizen Stephen Purvis, was arrested in April 2012.

All four men are being held in La Condesa, a prison for foreigners just outside Havana, after being questioned for months in other locations.

A number of other foreigners and Cubans who worked for the companies remain free but cannot leave the island because they are considered witnesses in the cases.

Cuban officials and lawyers for the defendants could not be reached for comment.

The legal limbo of the foreign executives has put a strain on Cuba’s relations with their home countries, where the legal process protects suspects from lengthy incarceration without charges, diplomats told Reuters.

Cuba says the cases are being handled within the letter of Cuban law. Attorney General Dario Delgado told Reuters late last year that the investigation had proved complex and lengthy.

“These cases, which involve economic crimes, are very complicated. They do not involve, for example, traffic violations or a murder,” he said.

Comptroller General Gladys Bejerano has said the length of investigations depended on the behavior of those involved.

“When there is fraud, tricks and violations … false documents, false accounting … there is no transparency and the process becomes more complicated because a case must be documented with evidence before going to trial,” she said.

Transparency International, considered the world’s leading anti-graft watchdog, last rated Cuba 58 out of 178 countries in terms of tackling corruption, ahead of all but eight of 33 nations in Latin America and the Caribbean.

Soon after taking over for his ailing brother Fidel in 2008, President Raul Castro established the comptroller general’s office with a seat on the ruling Council of State, even as he began implementing market-oriented economic reforms.

The measure marked the start of the anti-corruption campaign. Since then, high-level graft has been uncovered in several key areas, from the cigar, nickel and communications industries, to food processing and civil aviation.

Rodrigo Malmierca, the minister of foreign commerce, last week delivered a report to the cabinet highlighting “irregularities” in foreign joint venture companies, according to state-run media.

Malmierca blamed “the lack of rigor, control and exigency” of the deals “as well as the conduct and attitudes of the officials implicated,” the reports said.

Castro has been less successful, however, in tackling low salaries and lack of transparency, which contribute to the problem, according to foreign diplomats and businessmen.

There is no open bidding in Cuba’s import-export sector and state purchasers who handle multimillion-dollar contracts earn anywhere from $50 to $100 per month.