The proceedings of the Association for the Study of the Cuban Economy’s 23rd Annual Meeting entitled “Reforming Cuba?” (August 1–3, 2013) is now available. The presentations have now been published by ASCE at http://www.ascecuba.org/.

The presentations are listed below and linked to their sources in the ASCE Web Site.

Panorama de las reformas económico-sociales y sus efectos en Cuba, Carmelo Mesa-Lago

Crítica a las reformas socioeconómicas raulistas, 2006–2013, Rolando H. Castañeda

Nuevo tratamiento jurídico-penal a empresarios extranjeros: ¿parte de las reformas en Cuba?, René Gómez Manzano

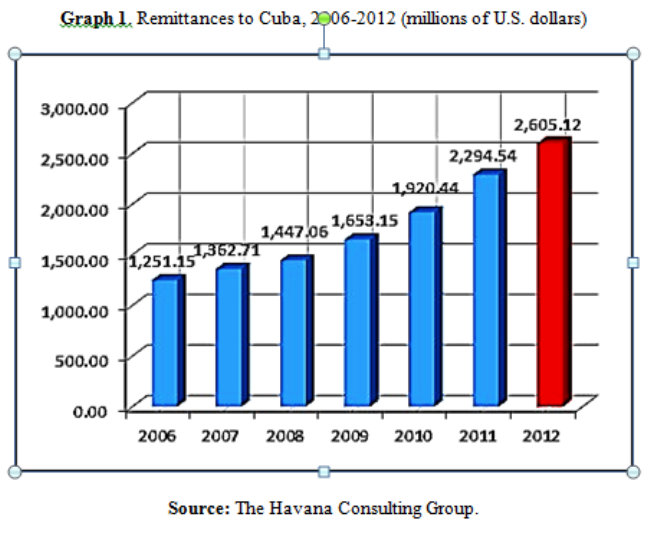

Reformas en Cuba: ¿La última utopía?, Emilio Morales

Potentials and Pitfalls of Cuba’s Move Toward Non-Agricultural Cooperatives, Archibald R. M. Ritter

Las reformas en Cuba: qué sigue, qué cambia, qué falta, Armando Chaguaceda and Marie Laure Geoffray

Cuba: ¿Hacia dónde van las “reformas”?, María C. Werlau

Resumen de las recomendaciones del panel sobre las medidas que debe adoptar Cuba para promover el crecimiento económico y nuevas oportunidades, Lorenzo L. Pérez

Immigration and Economics: Lessons for Policy, George J. Borjas

The Problem of Labor and the Construction of Socialism in Cuba: On Contradictions in the Reform of Cuba’s Regulations for Private Labor Cooperatives, Larry Catá Backer

Possible Electoral Systems in a Democratic Cuba, Daniel Buigas

The Legal Relations Between the U.S. and Cuba, Antonio R. Zamora

Cambios en la política migratoria del Gobierno cubano: ¿Nuevas reformas?, Laritza Diversent

The Venezuela Risks for PetroCaribe and Alba Countries, Gabriel Di Bella, Rafael Romeu and Andy Wolfe

Venezuela 2013: Situación y perspectivas socioeconómicas, ajustes insuficientes, Rolando H. Castañeda

Cuba: The Impact of Venezuela, Domingo Amuchástegui

Should the U.S. Lift the Cuban Embargo? Yes; It Already Has; and It Depends!, Roger R. Betancourt

Cuba External Debt and Finance in the Context of Limited Reforms, Luis R. Luis

Cuba, the Soviet Union, and Venezuela: A Tale of Dependence and Shock, Ernesto Hernández-Catá

Competitive Solidarity and the Political Economy of Invento, Roberto I. Armengol

The Fist of Lázaro is the Fist of His Generation: Lázaro Saavedra and New Cuban Art as Dissidence, Emily Snyder

La bipolaridad de la industria de la música cubana: La concepción del bien común y el aprovechamiento del mercado global, Jesse Friedman

Biohydrogen as an Alternative Energy Source for Cuba, Melissa Barona, Margarita Giraldo and Seth Marini

Cuba’s Prospects for a Military Oligarchy, Daniel I. Pedreira

Revolutions and their Aftermaths: Part One — Argentina’s Perón and Venezuela’s Chávez, Gary H. Maybarduk

Cuba’s Economic Policies: Growth, Development or Subsistence?, Jorge A. Sanguinetty

Cuba and Venezuela: Revolution and Reform, Silvia Pedraza and Carlos A. Romero Mercado

Mercado inmobiliario en Cuba: Una apertura a medias, Emilio Morales and Joseph Scarpaci

Estonia’s Post-Soviet Agricultural Reforms: Lessons for Cuba, Mario A. González-Corzo

Cuba Today: Walking New Roads? Roberto Veiga González

From Collision to Covenant: Challenges Faced by Cuba’s Future Leaders, Lenier González Mederos

Proyecto “DLíderes”, José Luis Leyva Cruz

Notes for the Cuban Transition, Antonio Rodiles and Alexis Jardines

Economistas y politólogos, blogueros y sociólogos: ¿Y quién habla de recursos naturales? Yociel Marrero Báez

Cambio cultural y actualización económica en Cuba: internet como espacio contencioso, Soren Triff

From Nada to Nauta: Internet Access and Cyber-Activism in A Changing Cuba, Ted A. Henken and Sjamme van de Voort

Technology Domestication, Cultural Public Sphere, and Popular Music in Contemporary Cuba, Nora Gámez Torres

Internet and Society in Cuba, Emily Parker

Poverty and the Effects on Aversive Social Control, Enrique S. Pumar

Cuba’s Long Tradition of Health Care Policies: Implications for Cuba and Other Nations, Rodolfo J. Stusser

A Century of Cuban Demographic Interactions and What They May Portend for the Future, Sergio Díaz-Briquets

The Rebirth of the Cuban Paladar: Is the Third Time the Charm? Ted A. Henken

Trabajo por cuenta propia en Cuba hoy: trabas y oportunidades, Karina Gálvez Chiú

Remesas de conocimiento, Juan Antonio Blanco

Diaspora Tourism: Performance and Impact of Nonresident Nationals on Cuba’s Tourism Sector, María Dolores Espino

The Path Taken by the Pharmaceutical Association of Cuba in Exile, Juan Luis Aguiar Muxella and Luis Ernesto Mejer Sarrá