From the Inter-Americanj Dialogue’s “Latin America Adviser” comes some interesting comments on the feasibility of shifting half of Cuba’s economy as measured by GDP to the non-state sector. The analysts are undoubtedly correct in arguing that the conditions are not yet in placed to permit an expansion of the private sector so as to constitute 50% of the economy.

However, as a statement of intention, Hernández comment is interesting. This objective may provide the impetus for intensifying the reform process in order to permit the expansion of the non-state sector to occur.

The original is located here: Inter-American Dialogue, Latin America Adviser, May 11, 2012

Question:

Cuba wants to move nearly half of its economy to the “non-state” sector within the next five years, Communist Party official Lazo Hernández said last month in a speech in Havana. Currently, government-run businesses account for 95 percent of the island’s GDP, said Hernández. Is the plan to move almost half of the country’s economy to private businesses realistic? Can the country’s tiny private sector absorb such an effort? Would such a move strengthen Cuba’s economy?

Answers:

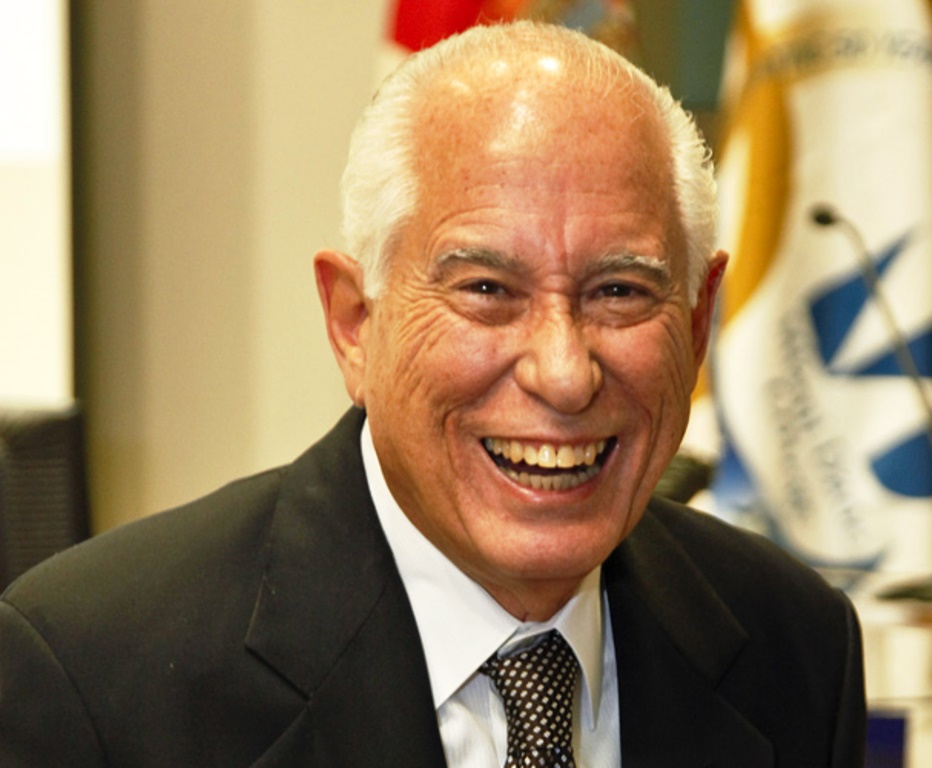

José Azel, senior scholar at the Institute for Cuban and Cuban- American Studies at the University of Miami:

“Lazo Hernández announced that the country is seeking to transform its economy by increasing the economic participation of the ‘non-state’ sector tenfold. To accomplish this, the government is relying on its Draft Guidelines for Economic and Social Policy. This document proposes to chart Cuba’s economic future and states paradoxically that ‘central planning and not the market will be supreme in the actualization of the economic model.’ The centerpiece of this plan revolves around firing as many as a million state employees (20 percent of the workforce) who could then solicit licenses to become self-employed as ‘cuentapropistas‘ in precisely 181 specified trades.

Moreover, the guidelines insist that prices will be set according to the dictates of central planning and the plan will insure that any new ‘non-state’ economic activities (apparently the term ‘private sector’ is not to be spoken) do not lead to the accumulation of wealth. To fully appreciate the economic surrealism of the Cuban ‘reforms,’ it is useful to examine a handful of the 181 trades and activities that are authorized for self-employment and which are foreseen as becoming 50 percent of the country’s economic activity. These include: trimming palm trees, cleaning spark plugs, refilling disposable cigarette lighters, mattress repair, wrapping buttons with fabric, umbrella repair and natural fruit peeling. This bizarre list of permitted private service sector activities will not drive the economic development of the country. Cuba’s GDP today is made up primarily by tourism, the services of doctors abroad, nickel and a handful of agricultural exports. Hernández’s stated goal seems mathematically impossible given a private sector permitted only in subsistence-level activities. An impediment to real reforms is simply that without inspired democratic leadership, the set of long-held Marxist economic assumptions will not be swapped for another set of economic beliefs. These are not reforms to unleash the market’s ‘invisible hand,’ but rather to reaffirm the Castros’ clinched fist.”

Lorenzo Perez, member of the Association for the Study of the Cuban Economy and former deputy director of the Middle East and Central Asia Department at the IMF:

“An expansion of Cuba’s private sector will certainly strengthen the economy. The realism of moving half of the economy to the private sector over a five-year period will depend on the measures taken to attain this goal. While positive steps have been taken in recent months, the measures up to now have been too timid or contradictory to attain this goal. A significant expansion of the private sector would require the opening of most sectors of the economy to private initiatives, respect for private property and the rule of law, freedom for markets to operate and the establishment of a sustainable macroeconomic framework. The activities opened to the private sector are too few (some 200 activities) and continue to limit most private professional activities, thereby negating possible benefits from the country’s well-educated labor force. Insufficient institutional arrangements have been adopted to establish clear property rights and promote the creation of private companies. For example, land distributed to farmers has only been leased, while the creation of companies with unlimited capacity to hire labor is not envisaged. Markets are not operating freely; a substantial amount of food production has to be sold to the state at fixed prices, the private sector cannot carry out most foreign trade activities and a heavy tax burden discourages private investment and hiring. A sustainable macroeconomic framework does not exist with public finances and the balance of payments depends on politically motivated financial relations with Venezuela. No effective measures have been taken to restructure the external debt with most industrialized countries, including negotiations with the United States to settle political differences. As a result, Cuba continues to be isolated from the international economy and organizations.”

Carmelo Mesa-Lago, distinguished professor emeritus of economics and Latin American studies at the University of Pittsburgh:

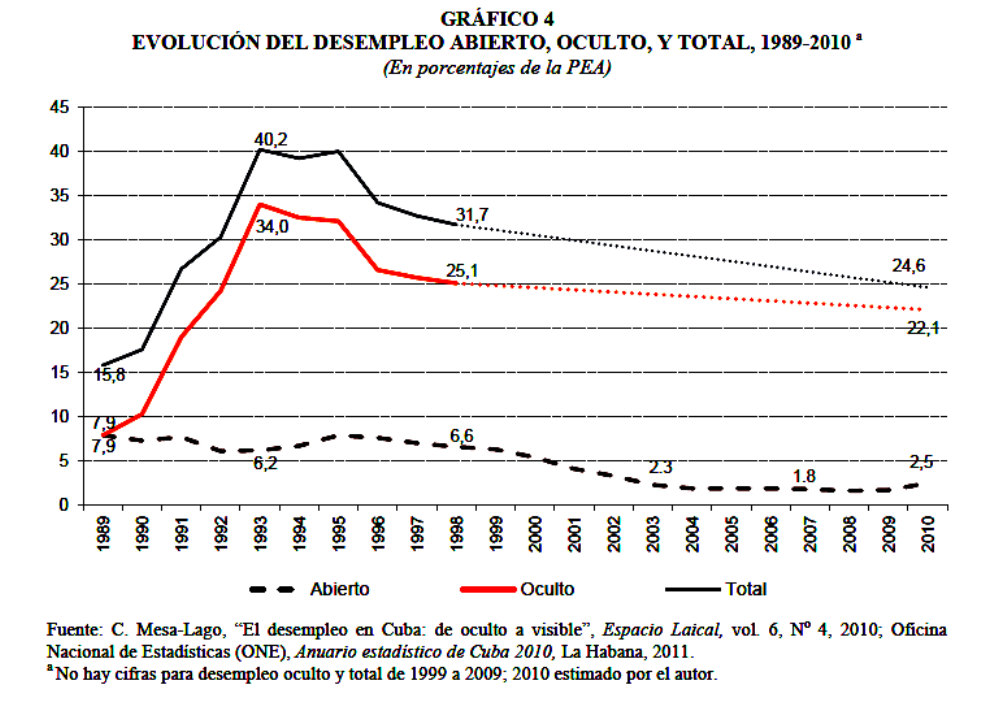

“The plan to generate half of GDP from the non-state sector requires that 1.8 million workers are transferred from the state sector by 2014, tantamount to 35 percent of the labor force. In 2006-2010, the non-state sector shrank. Under Raúl’s reforms, the government dismissed only 140,000 unneeded state workers in 2011 (14 percent of the target). In that year, there were 357,000 self-employed people (7 percent of the labor force) out of which 209,600 were new and only 17 percent had been unemployed. In addition, from 2009 to 2011, 147,000 agricultural producers were granted usufruct contracts in unused state land (2.9 percent of the labor force), but much less in 2011 alone. Finally 1,500 cooperatives in production and services were created in 2011; the number of members has not been released but assuming 4 members per coop there would be 6,000 (0.1 percent). In summary, perhaps 300,000 jobs in the non-state sector were created in 2011 (5.8 percent of the labor force), which means that 1.5 million non-state jobs must be created in the next three years to reach the 1.8 million target, at an annual average of 500,000. That is impossible at last year’s growth rate. Thus, the structural reforms must be accelerated and deepened, for example, through significant tax cuts in the non-state sector, an expansion of self-employment to university graduates and the elimination of bureaucratic impediments. If this were the case and the targets of state worker dismissals and non-state job creation were met, then the economy would probably be strengthened. The state would save a lot on wages and the private sector, which has proven to be more efficient than the state sector, should increase production and productivity. But a lot of ‘ifs’ must materialize.”

Uva de Aragón, associate director of the Cuban Research Institute at Florida International University:

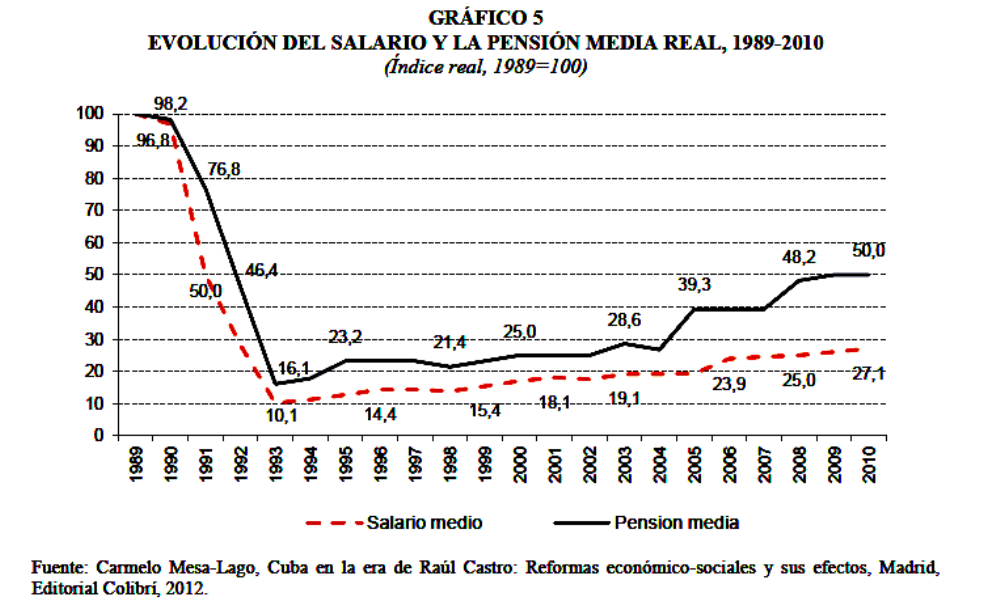

“It isn’t an easy goal, but it could be attainable if there is: 1) a change of mentality and acceptance that actors in the nonstate economic sector have a right to profits, and that the creation of a middle class would be healthy for the country; 2) a transparent legal framework; 3) a tax code based on profits, with a moratorium of at least two years for new businesses; 4) expansion of the areas in which the non-estate sector can grow; 5) reduction and eventual elimination of bureaucratic red tape; 6) access to tools and raw materials, in a timely manner and at reduced costs; 7) sustainable markets, which will require among other things higher salaries and pensions for remaining state employees and retirees, respectively; 8) significant advance in technology; 9) training of Cubans in businesses practices; 10) restructuring of monetary policies (the disparity between salaries in Cuban pesos and cost of products in convertible pesos cannot be maintained) and 11) capital. Where will the capital come from? Can a climate of stability be created to entice foreign investors? Will they allow Cubans in the diaspora to invest, even if only as partners with their relatives and friends? As changes take place, can the state continue to provide a safety net—education, healthcare, social services— for most Cubans? The changes needed are so deep they cannot be done too quickly; but a slow pace is as dangerous. Will Cuba find the needed steady rhythm to transform itself? I personally hope it does.”

José Azel, Uva de Aragon, Carmelo Mesa-Lago and Lorenzo Peréz

José Azel, Uva de Aragon, Carmelo Mesa-Lago and Lorenzo Peréz