COMPLETE DOCUMENT: Foro Cubano – Indicadores

Coordinador: Pavel Vidal Alejandro

ASCE: Cuba in Transition: Volume 25

Papers and Proceedings of the Twenty-Fifth Annual Meeting, July 30-August 1, 2015

All papers are hyperlinked to the ASCE Website and can be seen in PDF format.

Reflections on the State of the Cuban Economy Carlos Seiglie

¿Es la Economía o es la Política?: La Ilusoria Inversión de K. Marx Alexis Jardines

Los Grandes Retos del Deshielo Emilio Morales

Preparing for a Full Restoration of Economic Relations between Cuba and the United States Ernesto Hernández-Catá

Economic Consequences of Cuba-U.S. Reconciliation Luis R. Luis

El Sector Privado y el Turismo en Cuba Ante un Escenario de Relaciones con Estados Unidos José Luis Perelló Cabrera

The Logical Fallacy of the New U.S.-Cuba Policy and its Security Implications José Azel

Why Cuba is a State Sponsor of Terror Joseph M. Humire

The National Security Implications of the President’s New Cuba Policy Ana Quintana

Factores Atípicos de las Relaciones Internacionales Económicas de Cuba: El Rol de los Servicios Cubanos de Inteligencia Enrique García

Entrepreneurship in Post-Socialist Economies: Lessons for Cuba Mario A. González-Corzo

When Reforms Are Not: Recent Policy Development in Cuba and the Implications for the Future Enrique S. Pumar

Revisiting the Seven Threads in the Labyrinth of the Cuban Revolution Luis Martínez-Fernández

La Economía Política del Embargo o Bloqueo Interno Jorge A. Sanguinetty

Establishing Ground Rules for Political Risk Claims about Cuba José Gabilondo

Resolving U.S. Expropriation Claims Against Cuba: A Very Modest Proposal Matías F. Travieso-Díaz

U.S.-Cuba BIT: A Guarantee in Reestablishing Trade Relations Rolando Anillo, Esq.

Lessons from Cuba’s Party-Military Relations and a Tale of “Two Fronts Line” in North Korea Jung-chul Lee

Hybrid Economy in Cuba and North Korea: Key to the Longevity of Two Regimes and Difference Young-Ja Park

Historical Progress Of U.S.-Cuba Relationship: Implication for U.S.-North Korea Case Wootae Lee

Estimating Disguised Unemployment in Cuba Ernesto Hernández-Catá

Reliable Partners, Not Carpetbaggers Domingo Amuchástegui

Foreign Investment in Cuba’s “Updating” of Its Economic Model Jorge F. Pérez-López

Global Corporate Social Responsibility (GCSR) Standards With Cuban Characteristics: What Normalization Means for Transnational Enterprise Activity in Cuba Larry Catá Backer

Bienal de la Habana, 1984: Art Curators as State Researchers Paloma Checa-Gismero

Luchas y Éxitos de las Diásporas Cubana Lisa Clarke

A Framework for Assessing the Impact of U.S. Restrictions on Telecommunication Exports to Cuba Larry Press

Measures to Deal with an Aging Population: International Experiences and Lessons for Cuba Sergio Díaz-Briquets

Ernesto Hernández-Catá; January, 2014

The complete essay is here: STRUCTURE OF GDP, 2014. Hernandez-Cata

This paper presents estimates of Cuba’s gross domestic product (GDP) for the three principal sector of the economy: the government, the state enterprises, and the non-state sector. It estimates government GDP on the basis of fiscal data and derives non-state GDP from a combination of employment and productivity data. The article finds that the pronounced tendency for government output to increase faster than GDP was interrupted in 2010 and as the share of non-state production increased sharply. Nevertheless, the private share in the economy remains very low by international standards, and particularly in comparison to most countries in transition. The paper also derives estimates for gross national income. It finds that income is lower than GDP in the general government sector because of interest payments on Cuba’s external debt, while it exceeds production in the non-state sector owing to remittances from Cubans residing abroad.

The various estimates presented in this paper make it possible to reach a number of tentative conclusions.

ü The government share of GDP fell during the post-Soviet recession but then increased steadily all the way to 2009. The increase reflected the growth of current government expenditure; government investment—which accounts for the bulk of economy-wide capital formation—fell in percent of GDP. Total investment by all sectors also fell, to a very low level compared with the averages for other country groups and particularly for the emerging market and transition countries. The share of government spending declined from 2010 to 2011 following the financial crisis of 2008.

ü The share of the non-state sector GDP rose in the period 1993-1999 from a very low level in the Soviet-dominated period of the 1980’s. It changed little in the first decade of the XXIst century, but surged in 2011-2012 reflecting a transfer of employees form the state sector. Nevertheless, the non-state and private sector shares of the economy remains very small by international standards and notably by the standards of the countries in transition.

ü The relative importance of the state enterprises appears to have declined all the way from 1995 to 2009, but it has recovered somewhat since then.

ü National income in the government sector is lower than GDP because of interest payments on the external debt and, apparently, because of official transfers to foreigners.

ü By contrast, income in the non-state sector exceeds GDP by a growing margin, essentially because of dollar remittances from Cuban-Americans abroad. Thus, in that sector income from domestic production is being increasingly supplemented by income from abroad.

ü There is a statistically significant tendency for government current spending to crowd out the output of the state enterprises. Non-state output, on the other hand, appears to evolve mainly in response to official decisions to liberalize or to repress the non-state sector

Finally, there is a major problem whose resolution is beyond the scope of this article but which must at least be noted. The Cuban authorities assume that data for transactions denominated in foreign currency should be translated into local currency at the fixed exchange rate of one peso (CUP) per U.S. dollar. Under this convention (which is retained in this paper) dollar values are identical to peso values. Historically, however, the exchange value of the peso applicable to households and tourists has been much lower and it is currently CUP 24 per dollar. Clearly, the 1:1 exchange rate assumption introduces major distortions in the national accounts and in the balance of payments. For example, the peso value of exports of at least some goods and services (nickel, sugar and tourism among others) is grossly under estimated, while the dollar value of consumption is grossly over-estimated. In the income accounts, the dollar value of wages (mostly denominated in CUPs) is overestimated while the peso value of private remittances is under-estimated—although this is partly offset by an under-estimation of the peso value of interest payments abroad.

The task of disentangling all the elements of bias introduced by the use of a 1:1 conversion factor would be daunting. For the time being the corresponding distortions would have to be accepted, although they should be recognized. The good news is that the Cuban authorities are in the process of unifying the existing multiple exchange rate system, too slowly hélàs, but fairly surely. One important result of this change will be to the adoption of a single exchange rate for all transactions and all sectors, as well as for the purpose of statistical conversion.

The proceedings of the Association for the Study of the Cuban Economy’s 23rd Annual Meeting entitled “Reforming Cuba?” (August 1–3, 2013) is now available. The presentations have now been published by ASCE at http://www.ascecuba.org/.

The presentations are listed below and linked to their sources in the ASCE Web Site.

Panorama de las reformas económico-sociales y sus efectos en Cuba, Carmelo Mesa-Lago

Crítica a las reformas socioeconómicas raulistas, 2006–2013, Rolando H. Castañeda

Nuevo tratamiento jurídico-penal a empresarios extranjeros: ¿parte de las reformas en Cuba?, René Gómez Manzano

Reformas en Cuba: ¿La última utopía?, Emilio Morales

Potentials and Pitfalls of Cuba’s Move Toward Non-Agricultural Cooperatives, Archibald R. M. Ritter

Las reformas en Cuba: qué sigue, qué cambia, qué falta, Armando Chaguaceda and Marie Laure Geoffray

Cuba: ¿Hacia dónde van las “reformas”?, María C. Werlau

Resumen de las recomendaciones del panel sobre las medidas que debe adoptar Cuba para promover el crecimiento económico y nuevas oportunidades, Lorenzo L. Pérez

Immigration and Economics: Lessons for Policy, George J. Borjas

The Problem of Labor and the Construction of Socialism in Cuba: On Contradictions in the Reform of Cuba’s Regulations for Private Labor Cooperatives, Larry Catá Backer

Possible Electoral Systems in a Democratic Cuba, Daniel Buigas

The Legal Relations Between the U.S. and Cuba, Antonio R. Zamora

Cambios en la política migratoria del Gobierno cubano: ¿Nuevas reformas?, Laritza Diversent

The Venezuela Risks for PetroCaribe and Alba Countries, Gabriel Di Bella, Rafael Romeu and Andy Wolfe

Venezuela 2013: Situación y perspectivas socioeconómicas, ajustes insuficientes, Rolando H. Castañeda

Cuba: The Impact of Venezuela, Domingo Amuchástegui

Should the U.S. Lift the Cuban Embargo? Yes; It Already Has; and It Depends!, Roger R. Betancourt

Cuba External Debt and Finance in the Context of Limited Reforms, Luis R. Luis

Cuba, the Soviet Union, and Venezuela: A Tale of Dependence and Shock, Ernesto Hernández-Catá

Competitive Solidarity and the Political Economy of Invento, Roberto I. Armengol

The Fist of Lázaro is the Fist of His Generation: Lázaro Saavedra and New Cuban Art as Dissidence, Emily Snyder

La bipolaridad de la industria de la música cubana: La concepción del bien común y el aprovechamiento del mercado global, Jesse Friedman

Biohydrogen as an Alternative Energy Source for Cuba, Melissa Barona, Margarita Giraldo and Seth Marini

Cuba’s Prospects for a Military Oligarchy, Daniel I. Pedreira

Revolutions and their Aftermaths: Part One — Argentina’s Perón and Venezuela’s Chávez, Gary H. Maybarduk

Cuba’s Economic Policies: Growth, Development or Subsistence?, Jorge A. Sanguinetty

Cuba and Venezuela: Revolution and Reform, Silvia Pedraza and Carlos A. Romero Mercado

Mercado inmobiliario en Cuba: Una apertura a medias, Emilio Morales and Joseph Scarpaci

Estonia’s Post-Soviet Agricultural Reforms: Lessons for Cuba, Mario A. González-Corzo

Cuba Today: Walking New Roads? Roberto Veiga González

From Collision to Covenant: Challenges Faced by Cuba’s Future Leaders, Lenier González Mederos

Proyecto “DLíderes”, José Luis Leyva Cruz

Notes for the Cuban Transition, Antonio Rodiles and Alexis Jardines

Economistas y politólogos, blogueros y sociólogos: ¿Y quién habla de recursos naturales? Yociel Marrero Báez

Cambio cultural y actualización económica en Cuba: internet como espacio contencioso, Soren Triff

From Nada to Nauta: Internet Access and Cyber-Activism in A Changing Cuba, Ted A. Henken and Sjamme van de Voort

Technology Domestication, Cultural Public Sphere, and Popular Music in Contemporary Cuba, Nora Gámez Torres

Internet and Society in Cuba, Emily Parker

Poverty and the Effects on Aversive Social Control, Enrique S. Pumar

Cuba’s Long Tradition of Health Care Policies: Implications for Cuba and Other Nations, Rodolfo J. Stusser

A Century of Cuban Demographic Interactions and What They May Portend for the Future, Sergio Díaz-Briquets

The Rebirth of the Cuban Paladar: Is the Third Time the Charm? Ted A. Henken

Trabajo por cuenta propia en Cuba hoy: trabas y oportunidades, Karina Gálvez Chiú

Remesas de conocimiento, Juan Antonio Blanco

Diaspora Tourism: Performance and Impact of Nonresident Nationals on Cuba’s Tourism Sector, María Dolores Espino

The Path Taken by the Pharmaceutical Association of Cuba in Exile, Juan Luis Aguiar Muxella and Luis Ernesto Mejer Sarrá

The Association for the Study of the Cuban Economy established a Blog some months ago. It promises to be the locus of timely and serious economic analyses and commentaries on the Cuban economy.

The location of the Blog is http://www.ascecuba.org/blog/

.

The Table of Contents as of January 6 2013 was as follows. Each article is linked to the original location on the ASCE Blog.

.

Cuba’s External Debt Problem: Daunting Yet Surmountable by Luis R. Luis

The external debt of Cuba is not excessively large relative to GDP, though this is distorted by an overvalued currency and the reliance on non-cash services exports. Recent bilateral restructurings are easing the debt burden but are insufficient to lift creditworthiness and restore access to international financial markets. [More]

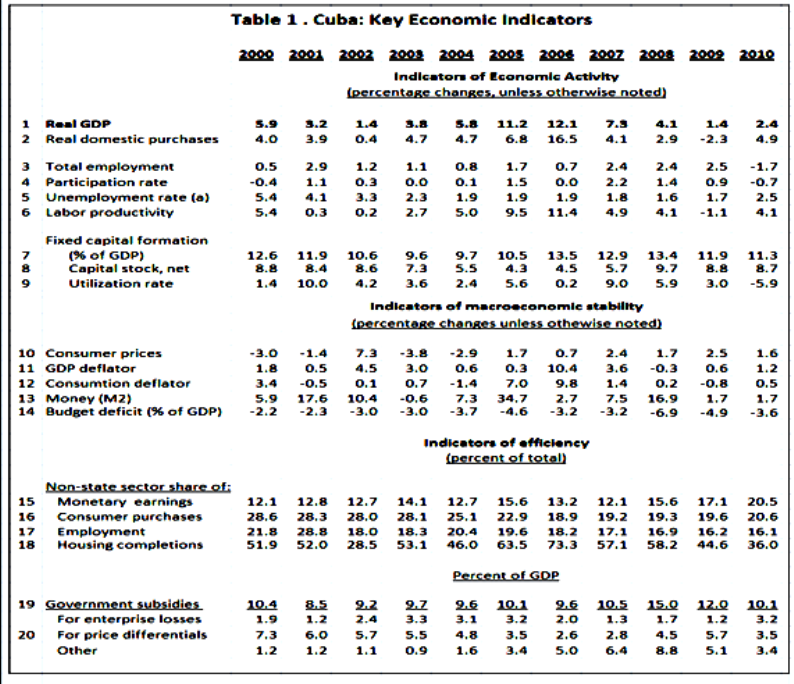

Controls, Subsidies and the Behavior of Cuba’s GDP Price Deflator by Ernesto Hernández-Catá

In this paper a model of overall price behavior for the Cuban economy is estimated. The model, despite limitations, explains reasonably well the path of the GDP deflator. Importantly, the model sheds light on the interaction between unit labor costs, consumption subsidies and the behavior of prices in the economy. [More]

A Triumph of Intelligence: Cuba Moves Towards Exchange Rate Unification by Ernesto Hernández-Catá

The movement towards a unified exchange rate is positive, though a gradualist approach presents some dangers, argues Ernesto Hernandez-Cata in this post. [More]

La Senda de Cuba para Aumentar la Productividad by Rolando Castaneda

Este artículo de Rolando Castañeda señala la necesidad de estimular la actividad privada propiamente dicha para alcanzar mayor productividad y empleo como han demostrado un gran número de economías en transición. [More]

Another Cuban Statistical Mystery by Ernesto Hernández-Catá

Ernesto Hernandez-Cata estimates the net value of Cuban donations abroad. [More]

La Estructura Institucional del Producto Interno Bruto en Cuba by Ernesto Hernández-Catá

Este trabajo presenta estimaciones de la estructura del PIB cubano para el gobierno, empresas del estado y el sector no estatal e ilustra la relativamente baja contribución del sector privado a la economía. [More]

The members of ASCE are deeply saddened by the news of the passing after a long illness of Oscar Espinosa Chepe in Madrid on September 23.[More]

Convertible Pesos: How Strong is the Central Bank of Cuba? by Luis R. Luis

In this post Luis R. Luis analyzes implications of the lack of full dollar backing for the convertible Cuban peso (CUC), one of the two national currencies circulating in Cuba. [More]

Government Support to Enterprises in Cuba by Ernesto Hernández-Catá

This post looks at state support to Cuban enterprises and uncovers that net transfers are again rising. The reasons for this are not always clear but Ernesto Hernandez-Cata offers a plausible explanation. [More]

A Political Economy Approach to the Cuban Embargo by Roger Betancourt

Roger Betancourt analyzes the evolution of the Cuban embargo and shows that some parts have already been lifted. Verifiable human rights guarantees may provide a way to elicit political support in the US for action to change trade and financial elements of the embargo. [More]

Cinco mitos sobre el sistema cambiario cubano by Ernesto Hernández-Catá

Ernesto Hernández-Catá comenta sobre el sistema de cambios múltiples vigente en Cuba. [More]

La dualidad monetaria en Cuba: Comentario sobre el artículo de Roberto Orro by Joaquin P. Pujol

Joaquín P. Pujol comenta en esta nota sobre la dualidad monetaria en Cuba. [More]

Unificación monetaria en Cuba: ¿quimera o realidad? by Roberto Orro

En este artículo Roberto Orro describe el complejo sistema monetario y cambiario de Cuba y sugiere que la unificacion monetaria no está a la vista. [More]

Consumption v. Investment: Another Duality of the Cuban Economy by Roberto Orro

Roberto Orro argues in this article that the Cuban economy experienced two distinct periods where either investment or consumption prevailed. This behavior was influenced by external factors among them the assistance derived from the Soviet Union as contrasted to that coming presently from Venezuela. [More]

Gauging Cuba’s Economic Reforms by Luis R. Luis

In this post Luis R. Luis gauges the progress of Cuba’s recent economic reforms using Transition Indicators developed by the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD). [More]

On the Economic Impact of Post-Soviet and Post-Venezuelan Assistance to Cuba by Ernesto Hernández-Catá

The end of Venezuelan aid to Cuba will have a sizable negative impact on the economy though very likely of lesser magnitude than the withdrawal of Soviet assistance in the 1990’s concludes Ernesto Hernandez-Cata in this article. [More]

The Significant Assistance of Venezuela to Cuba: How Long Will it Last? by Rolando Castaneda

Rolando H. Castaneda argues that the high levels of Venezuelan aid to Cuba are unsustainable and constitute a heavy burden for both countries even for Cuba in the medium-term as the assistance allows the postponement of essential economic reforms. [More]

Cuba: The Mass Privatization of Employment Started in 2011 by Ernesto Hernández-Catá

In this post Ernesto Hernandez-Cata analyzes Cuban labor market data, identifying large sectoral changes in employment that signal the beginning of large scale privatization of employment in the island. [More]

How Large is Venezuelan Assistance to Cuba? by Ernesto Hernández-Catá

In this article Ernesto Hernandez-Cata explores Cuban official statistics to show that Venezuelan subsidies rival or exceed those flowing from the former Soviet Union during the 1980s. This raises questions of sustainability and severe adjustment for both countries. [More]

Cuba Ill-Prepared for Venezuelan Shock by Luis R. Luis

Cuba’s weak international accounts and liquidity and lack of access to financial markets place the country in a difficult position to withstand a potential cut in Venezuelan aid argues Luis R. Luis. The failure of reforms to boost farm output and merchandise exports make the economy highly dependent on Venezuelan aid and remittances from Cubans living abroad. [More]

Recently there have been several estimates of Venezuelan economic assistance to Cuba—for example by Lopez (2012) and Mesa-Lago (2013). My latest estimates suggest that payments from Venezuela increased rapidly during the first decade of the XXI century and peaked at almost 19% of Cuba’s GDP) in 2009. They declined over the following two years but remained quite large: I estimate Venezuelan assistance in 2011 (the last year for which the required data are available) at just over $7 billion, or 11 % of Cuba’s GDP. These numbers are large, and they have invited comparisons with Soviet assistance to Cuba in the late 1980s. It has been implied that the adverse effect on Cuba’s real GDP of ending Venezuelan aid would be similar in size to the devastating impact of the elimination of Soviet aid in 1990. This is almost certainly wrong.

The analysis presented in this paper indicates that a complete cancellation of Venezuelan assistance to Cuba would cause considerably less damage than the elimination of Soviet assistance in the early 1990s, with the fall in real GDP estimated at somewhere between 7% and 10%, compared to 38% after the breakdown of Cuban/Soviet relations. Moreover, if the Cuban government were to avoid the policies of subsidization and inflationary finance pursued in the post-Soviet period, the post-Venezuelan contraction would be at the lower end of the range or approximately 7%.

This is still a lot, however. To be sure, the danger of a sudden elimination of aid inflows has diminished considerably since the Venezuelan election of April 2013. Nevertheless, the prospect of a more gradual reduction in aid remains likely given Venezuela’s economic difficulties. In that case, the effect would be a reduction in the growth of the Cuban economy spread over several years, rather than a sudden contraction of output. Furthermore, current efforts to obtain financing at non-market terms from other countries, like Algeria, Angola and Brazil, would, if successful, diminish the magnitude of the shock. But it would perpetuate dependence and delay the needed adjustment.

The only way to diminish the pain of reduced income and consumption would be a decisive effort to expand Cuba’s productive capacity by intensifying the reform process. The list of required actions is familiar to all: liberalize prices, unify the exchange rate system, dismantle exchange and trade controls, stop the bureaucratic interference with non-state agricultural producers, continue efforts to downsize employment in the state sector, and increase substantially the list of activities opened to the private sector, including (why not?) doctors, nurses, teachers and athletes. Private clinics and schools would pop up, consultancy services would flourish, and the baseball winter leagues would come back to life.

Karl Marx (1852) credited Hegel with the idea that history repeats itself twice. Unfortunately for him, he added: “the first time as a tragedy, the second time as a farce”. This is not necessarily true. Often the second time is also a tragedy, as when the West gave Eastern Europe to Stalin at Yalta, less than a decade after giving it to Hitler in Munich. And why couldn’t the second time be an epiphany? Cuba’s rulers now have a historic opportunity to allow people to improve their own standard of living, and to stop wasting resources to keep the faded and sinister red banner afloat. Without a doubt, history will absolve them if they take that chance. And then, perhaps, Cuba will be allowed to replace its politically inspired dependence on doubtful friends with free, mutually beneficial trade with all nations.

Ernesto Hernandez-Cata was born in Marianao, Havana, Cuba in 1942. He holds a License from the Graduate Institute of International Studies in Geneva, Switzerland; and a Ph.D. in economics from Yale University. For about 30 years through, Ernesto Hernandez-Cata worked for the International Monetary Fund where he held a number of senior positions. When he retired from the I.M.F. in July 2003 he was Associate Director of the African Department and Chairman of the Investment Committee of the Staff Retirement Plan. Previously he had served in the Division of International Finance of the Federal Reserve Board. From 2002 to 2007 Mr. Hernandez-Cata taught economic development and growth at the Paul Nitze School of Advanced International Studies of the University of Johns Hopkins. Previously he had taught macroeconomics and monetary policy at The American University.

Ernesto Hernández-Catá has agreed to have his recent essay “The Growth of the Cuban Economy in the First Decade of the XXI Century: Is it Sustainable?” posted on this Web Site. It was written for presentation at the forthcoming 22nd annual meeting of the Association for the Study of the Cuban Economy in Miami in August 2012. The full study is available here: Ernesto Hernandez-Cata, “The Growth of the Cuban Economy in the First Decade of the XXI Century”.

Income and production increased rapidly in Cuba during the first decade of the XXI century. Growth was fueled by a surge in government spending and a boom in services exports and investment—all of them made possible by rapidly increasing in payments received from Venezuela. The expansion in both domestic and foreign demand during the decade did not visibly result in higher inflation or in a massive deterioration of the country’s external position, partly because potential output also increased rapidly reflecting the strong performance of investment. (In this connection, it is a good thing that part of the Venezuelan money was used to finance capital formation rather than consumption.) However, capacity utilization also increased markedly, and the gap between actual and potential GDP must have dwindled considerably, leaving little room for supply to respond to additional demand pressures.

While there was no explosion in the current account of the balance of payments for most of the decade, severe pressures did emerge in 2008 and the authorities had to restrict imports, ration foreign exchange, and take measures that damaged the nation’s reputation in world financial markets. The Central Bank also intervened on a large scale to keep the exchange value of the Cuban peso fixed—a policy that cannot continue forever.

The large size of Cuba’s dependence on Venezuelan aid makes the country hostage to fortune. A sudden interruption in such aid would trigger a deep recession and put the balance of payments in a critical position. Therefore the structural measures that were taken or announced in 2009 and 2010 should now be extended and pursued much more aggressively. This will not be easy. But as Russia’s former Finance Minister Boris Fedorov once said, dependence on foreign largesse is a luxury that a free country cannot afford.[i]

Ernesto Hernandez-Cata was born in Havana, Cuba in 1942. He holds a License from the Graduate Institute of International Studies in Geneva, Switzerland; and a Ph.D. in economics from Yale University. For about 30 years through, Mr. Hernandez-Cata worked for the International Monetary Fund where he held a number of senior positions, including: Deputy Director of Research and coordinator of the World Economic Outlook; chief negotiator with the Russian Federation; and Deputy Director of the Western Hemisphere Department, concentrating on relations with the United States and Canada. When he retired from the I.M.F. in July 2003 he was Associate Director of the African Department\, where he dealt with Ethiopia, Guinea, Sierra Leone and the Democratic Republic of Congo, among other countries. He was also Chairman of the Investment Committee of the IMF’s Staff Retirement Plan. Previously he had served in the Division of International Finance of the Federal Reserve Board. From 2002 to2007 he taught economic development and growth at the Paul Nitze School of Advanced International Studies of the University of Johns Hopkins. Previously he had taught macroeconomics and monetary policy at The American University.

Ernesto Hernandez-Cata was born in Havana, Cuba in 1942. He holds a License from the Graduate Institute of International Studies in Geneva, Switzerland; and a Ph.D. in economics from Yale University. For about 30 years through, Mr. Hernandez-Cata worked for the International Monetary Fund where he held a number of senior positions, including: Deputy Director of Research and coordinator of the World Economic Outlook; chief negotiator with the Russian Federation; and Deputy Director of the Western Hemisphere Department, concentrating on relations with the United States and Canada. When he retired from the I.M.F. in July 2003 he was Associate Director of the African Department\, where he dealt with Ethiopia, Guinea, Sierra Leone and the Democratic Republic of Congo, among other countries. He was also Chairman of the Investment Committee of the IMF’s Staff Retirement Plan. Previously he had served in the Division of International Finance of the Federal Reserve Board. From 2002 to2007 he taught economic development and growth at the Paul Nitze School of Advanced International Studies of the University of Johns Hopkins. Previously he had taught macroeconomics and monetary policy at The American University.