Harvard Business Review, August 17, 2015

Original Article Here: What You Might Not Know  On the front page of a Cuban newspaper recently there was an item about a two-story home in the old city of Havana that crumbled—and that in the course of its collapse, killed four people. This is a harsh glimpse the physical reality facing many of the buildings across Havana and elsewhere in the country. But it’s also a metaphor for much of the Cuban economy. Cuba is, in many ways, an economy stuck in time and at risk of further unraveling.

On the front page of a Cuban newspaper recently there was an item about a two-story home in the old city of Havana that crumbled—and that in the course of its collapse, killed four people. This is a harsh glimpse the physical reality facing many of the buildings across Havana and elsewhere in the country. But it’s also a metaphor for much of the Cuban economy. Cuba is, in many ways, an economy stuck in time and at risk of further unraveling.

Cuba’s economy got a jolt in December 2014, when U.S.-Cuban ties were restored. The U.S. embassy in Havana has reopened. Some travel is easing. Pope Francis will visit in September. So on the surface, it might appear to be full steam ahead for business and beyond.

But in order to understand where Cuba may go, we need to understand where its economy, its people, its governance, and its marketplace have been. Cuba’s growth domestic product per capita in 2015 is approximately what it was in 1985. The short version of Cuba’s recent economic history is that it peaked in the last quarter of 1984 and began a slow slide during the second half of the 80s. It then suffered a catastrophic plunge in the first four years of the 1990s. To the extent that we can estimate, a third of the economy disappeared during this time and a slow recovery followed. There was a spike in the 2000s when Venezuela began to provide petroleum at deeply discounted market prices, and that peaked just before the 2008-09 financial crisis. After 2009, the Cuban economy really didn’t recover. For the most part it has remained at the alleged 2% growth rate, but given the unreliability of statistics from Cuba, it’s likely a lot closer to zero. That’s grim.

Cuba’s population, now shy of 11.2 million, is shrinking and rapidly aging. Cuba has been below the demographic replacement age since 1978. This is not a good scenario for productivity and economic growth. For that, you need people who are in the prime of the workforce. That’s not the Cuban demographic story. Cuba is closing primary schools and opening homes for the elderly, closing pediatric wards and opening geriatric wards. That’s a burden for growth, but also creates business activity and opportunity: Cuba suddenly needs to build retirement communities. Cuba projects a population of 10.8 million in 2030. It is about to go from around two million people over the age of 60 to 3.25 million in 2030.

But it isn’t all bleak. Cuban life expectancy is approximately what you would expect in North America and Western Europe. That means levels of education are good. It means there is access to basic, quality healthcare. It doesn’t mean that you can have a banquet every day, but that basic nutritional needs are met. There are opportunities for sports. These are the kinds of things that contribute to well-being and that require lots of effective institutional arrangements.

When you put all these pieces together around education and health care, it’s clear that Cuba is likely a champion of investment in the development of human capital—but for the last 50 years it has an extremely low economic return on this investment. If you invest in human capital, whether in your company or in your country, sooner or later it will pay off if you have the right set of incentives. In other words, you need the right organizational design so that all these well -trained, well-educated people will be able to do their work. That’s what Cuba doesn’t have.

But it does have a colossally well-trained work force. It is probably the best, most well-trained workforce at the cheapest labor-market price that any international investor could find anywhere in the world. You could find such first-rate people in Singapore, but they wouldn’t be cheap.

This is true despite the country’s very poor infrastructure. In Cuba, there are seven computers per 100 people — one of the lowest ratios in the Americas. Internet access in Cuba is very expensive. Consider that the median monthly salary in Cuba, when converted into dollars, is a bit below $20 a month. Then think about what you pay for a service like Netflix. For many Cubans even at a discount, half your monthly income would go to Netflix.

So how does Cuba make money? Its current principal source of revenue is the export of healthcare services by means of sending physicians, nurses, and healthcare technicians to countries like Venezuela and Brazil—an item that it has yet to record in its published official statistics.

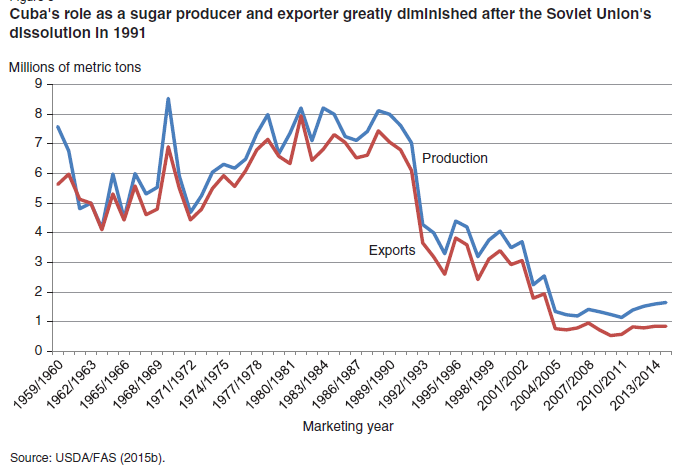

Cuba’s main resource to engage in the world is no longer sugar cane. It has tourism—beach and sun and one of the communist world’s last Jurassic political systems—but the real asset is the brains of its people. It could be an ideal location for healthcare organizations, but also for those in applied sciences, biotechnology, and pharmaceuticals. We know two things about biotech in Cuba. One is that the quality of applied science seems to be first rate. And secondly, the business model for Cuban biotechnology has been laughably bad. They know how to make new products. They don’t know how to market them effectively. That’s a solvable problem, yet they haven’t been able to do it, and so a partnership with a European or a Canadian or a U.S. pharmaceutical company could be a great asset in the future.

Have the doors opened to U.S. company investment? Well, no. The power to authorize U.S. business investment in Cuba still rests with the U.S. Treasury Department Office of Foreign Assets control (OFAC)—and the fact is this agency’s documentation contains the exact same formulation that it had before December 17. Economic transactions, trade, and investment with Cuba remain prohibited unless they are specifically authorized by OFAC. The Government of Cuba must also authorize each and every foreign investment from any country, and it has yet to authorize one from the United States.

A lot of people get hung up on the issue of travel between the U.S. and Cuba. JetBlue recently launched direct commercial flights from New York. But there have been charter flights from Miami to Cuba since the late 1970s. OFAC has made particular determinations authorizing different airlines as charter flights for many years for various travel programs to Cuba, especially for cultural, educational, and religious groups. There has been a U.S. embargo on economic transactions with Cuba since 1960. There are still restrictions on American tourist travel. Going to the beach is something that the neither the President of the United States nor OFAC can authorize. It requires an act of U.S. Congress. Congress decided in 2000 that it wanted to prohibit beach tourism and it didn’t want the president to have any discretion whatsoever on this point. Now, while more people will be allowed to visit, they still can’t go to the beach.

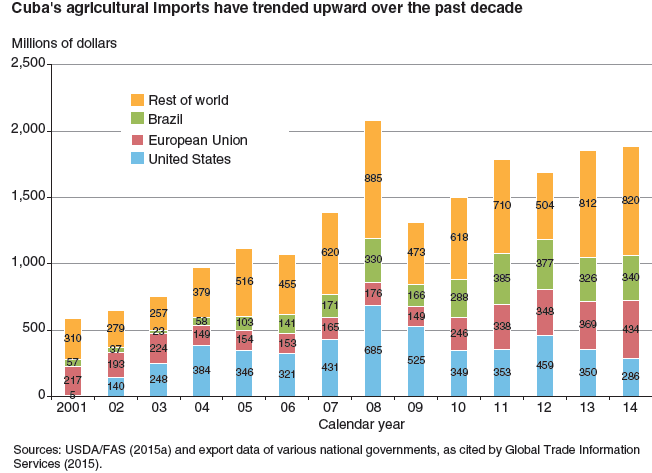

On the exports side, President George W. Bush authorized U.S. agricultural exports to Cuba in late 2001 under presidential discretion, which exceeded $5 billion between 2002 and 2014. But, oddly, U.S. agricultural exports to Cuba declined by over one-third (if you compare January-June 2014 to the same months in 2015) since the President Obama’s announcement. The boom in U.S.-Cuba trade has yet to materialize. Cuba does have a private sector, which it calls it the “non-state sector.” It includes mixed enterprises (foreign firms and state enterprises) and a “self-employment sector.” In a population just shy of 11.2 million, there are over 500,000 people who have self-employment licenses, according to President Raúl Castro’s report to Cuba’s National Assembly in July 2015. The rule of thumb among Cuban scholars who study this is for any one license there are on average four lawfully-hired employees. That would amount to over two million people in the self-employment sector.

One reason why the average number of employees is four is because, once you reach five or more employees, your tax rate goes up. The Cuban government’s tax collection system is primitive. There is no personal income tax in Cuba. There is no corporate tax in Cuba. There is no value added tax in Cuba. There is no sales tax in Cuba. But there is a tax on the number of your employees. This tax system discourages economic and job growth.

The Cuban government has a list of occupations that are authorized by name; everything else is prohibited or reserved for state-run enterprises. Authorized occupations include plumbers or electricians. These are skilled workers, but the list rarely includes those who studied at the university. Thus in a country that has invested so much in the development of a human capital, it says in effect: if you attended university, then you’re going to work for the state. Let’s say you go to the medical school at the University of Havana. Healthcare is a state sector, it’s not private activity. So what if you decide you want to make more money? You might realize that the one useful skill gained from your time at medical school is learning English. So, you quit as a physician and become a maid at a tourist hotel. You earn more money because your most marketable asset turns out to be that you can communicate in English. This is a tragedy for the individual and for the society. It turns incentives about acquiring skills upside down. You do have people with university training in the private sector, but often not working in the profession for which they trained. There are some exceptions—for example you could be a tutor in the private sector, but you cannot be a classroom teacher. You can, in the private sector, teach foreign languages, but you cannot teach mathematics. Thus the private sector is tiny.

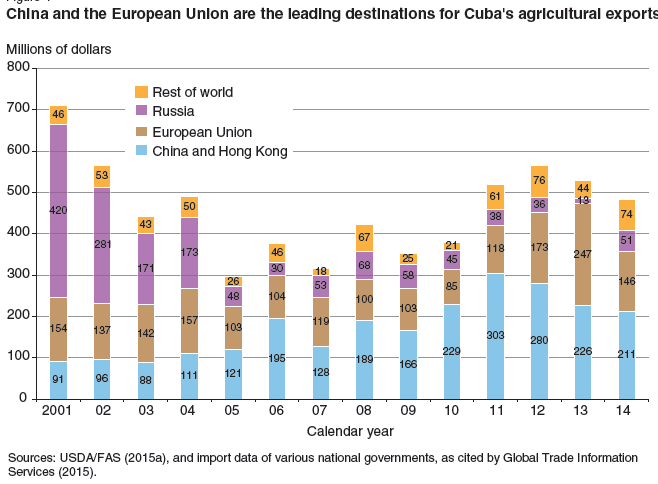

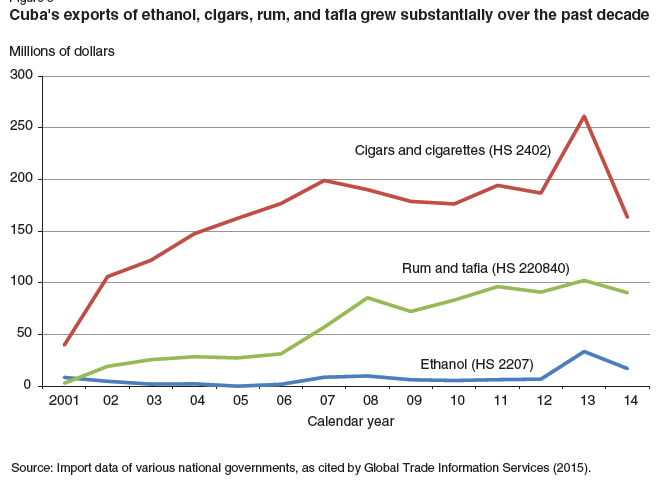

There is also foreign investment, although not a lot. The 2014 foreign investment law finally authorized wholly owned foreign enterprises, but thus far without exception they are all joint ventures with the government. Cuba’s trade reveals its international partners. In 2013 in U.S. dollar-equivalents, Cuba exported $343 million to China and imported $1.5 billion from it. In contrast, it exported $81 million to, and imported $614 million, from Brazil. Cuba exported $2.3 billion to, and imported $4.8 billion from, Venezuela, its top partner.

But China matters in one decisive way. The Chinese government strongly advocates that the Cuban government should reform its economy to achieve a faster, wider market opening. That’s not the way you might have guessed China would be advocating, hut in fact China’s role in Cuba is to try to persuade the Cuban government to emulate its own market opening.

The extraordinary competence of Cuba’s political leaders is sometimes easy to miss. They’re colossally impressive in the management of politics. They’ve remained in power. Who would have known that all communist regimes in Europe would collapse, but that only Cuba and four East Asian regimes would survive?

Cuba has a really, really well-educated and cheap workforce, as well as substantial evidence of entrepreneurial potential. If its political leaders can manage to lift constraints on investment, create the right incentives, and reform its tax code, the country could really boom. But that’s a lot of change to expect for the insular government of an island nation that’s otherwise stuck in time.

Jorge I. Dominguez is the Antonio Madero Professor for the Study of Mexico at Harvard University. He is the lead editor of a special issue on the Cuban economy for the journal Cuban Studies (2016).

Jorge I. Dominguez is the Antonio Madero Professor for the Study of Mexico at Harvard University. He is the lead editor of a special issue on the Cuban economy for the journal Cuban Studies (2016).