The Jacobin. October 12, 2016

https://www.jacobinmag.com/2016/10/alternative-cuba-socialism-left-opposition-worker-control/

By Samuel Farber

In July 2016, thanks to a 20 percent reduction in oil shipments from Venezuela, Cuba’s economy minister Marino Murillo announced a 6 percent cut in electricity and a 28 percent cut in fuel. Meanwhile, he ordered an immediate drop in public sector energy use, with consequent working-hour reductions for state employees, and warned of possible blackouts, raising the specter of the dark and hungry days of the Special Period of the nineties.

This turn of events delivered another blow to Raúl Castro’s attempts to establish a Cuban version of the Sino-Vietnamese model, which maintains a one-party state while opening the economy to private enterprise and the market.

In the political realm, this has meant a relaxation of state control over the citizenry. But this hasn’t been matched with democratization. For example, the 2012 emigration reform facilitated Cuban citizens’ movement in and out of the country, but did not recognize travel abroad as their right.

In the political realm, this has meant a relaxation of state control over the citizenry. But this hasn’t been matched with democratization. For example, the 2012 emigration reform facilitated Cuban citizens’ movement in and out of the country, but did not recognize travel abroad as their right.

In the economic realm, the government has implemented a modest and contradictory strategy. For example, the agricultural sector’s structural reforms provide land leases for a maximum of twenty years; the Chinese and Vietnamese governments, in contrast, established much longer and, in some cases, permanent contracts.

The government now allows self-employment in few occupations (a little over two hundred). Had it opened it up for the whole economy — reserving only those sectors regarded as high social priorities, like medicine — the reform would increase available products and services.

Complementary changes introduced to bolster these structural reforms — like the establishment of wholesale markets and commercial bank credits — have been inadequate and ended up negatively impacting the reform program. In addition, the bureaucratic and inefficient Acopio — the state agency with the monopoly power to buy most agricultural products at prices established by the government — has slowed agricultural production. As a result, harvested produce has spoiled while waiting to be processed at government plants.

The Castro regime’s half measures will, more likely than not, push Cuba closer to a form of state capitalism without democracy. But there is a feasible alternative for the country.

No Recovery

Until this new crisis, the Cuban economy had partially bounced back after the worst years of the Special Period, which devastated the country in the wake of the collapse of the Soviet bloc in the late eighties and early nineties.

The country hit bottom between 1992 and 1994, when extreme food shortages led to an outbreak of an optical neuropathy epidemic that affected some fifty thousand people. Since then, the Cuban economy has surpassed the GDP it achieved in 1989.

But other indicators — such as real wages and pensions, which in 2014 were still at 27 percent and 50 percent of their 1989 level, respectively — never came back. Meanwhile, social spending is still falling, and family consumption is expected to decline 2.8 percent in 2016 and 7.5 percent in 2017.

Although the hunger of the early nineties is gone, Cubans still struggle to find enough food. The much-praised development of organic and urban agriculture on the island represents a relatively small part of agricultural production. As Cuban economist C. Juan Triana Cordoví pointed out, declining domestic production has forced hotels to import vegetables, including yucca, the root-vegetable mainstay of the Cuban diet. The small progress in sustainable agriculture doesn’t make up for the fact that food production has never regained its 1989 level and that more than half of Cuba’s food supply comes from imports, at an annual cost of $2 billion.

Many of the revolution’s gains in education and health have also been lost. The teachers who fled the educational sector’s low pay haven’t been fully replaced, and private tutoring — often provided by public school teachers in their spare time — has grown exponentially. In addition, numerous school buildings, libraries, and laboratories are crumbling. Before the start of the current school year, 350 schools were closed after they were found to be in dangerous physical condition.

The same applies to many hospitals and other medical facilities, which now operate with skeleton crews: the government sends large numbers of general practitioners and specialists to Venezuela and other foreign countries in exchange for oil or hard currency.

The regime’s contradictory reforms will likely pass with the historic generation of leaders. Second-generation bureaucratic officials are likely to fully commit to the Sino-Vietnamese model, perhaps tilting somewhat toward Russia’s capitalism, which combines massive oligarchic theft of state property with a nominal “democracy” that would give US Congress the political cover it needs to repeal the 1996 Helms-Burton law and remove the island’s economic blockade.

Besides winning the United States’s enthusiasm, this new generation of leaders will enlist foreign capital and at least a sector of Cuban American capital by reassuring them that the government will maintain total control over the state, the mass media, and the mass organizations — including state-controlled unions — to guarantee their new capitalist investors, foreign and Cuban, peace, law, and order.

Yet there are other economic models that are being talked about inside and outside the government, although in a rather discreet fashion due, in great part, to the political system that does not allow a full and candid exploration of ideas.

Free and Rational

Mainstream critics have for some time been arguing for the establishment of a free-market economy, which they present as the only “rational” alternative to the bureaucratic economic management of Communist Party rule.

This group covers a wide spectrum, ranging from a hard free-market stance to a more social-democratic welfare state perspective. In this latter grouping, moderate critics overlap with sections of the island’s academic economists, including members of the Center for the Study of the Cuban Economy at the University of Havana.

Yet hardly any of these critics have openly addressed the question of what to do with the most important part of the Cuban economy, the larger state-owned enterprises. Instead, they focus on establishing private PYMEs — the Spanish language acronym for small and medium size enterprises — although they haven’t clarified what “medium” actually means.

They have also supported the government’s move toward replacing the universal rationing system with one that subsidizes categories of people instead of products. Today, all Cubans, regardless of income, can receive a number of products at low, subsidized prices. The new system would only provide these products to the poorest and most disadvantaged, thereby rationalizing agricultural markets and reducing the government’s budget. The government’s recent reduction of the number of products distributed by this system marks the first step in this means-tested direction.

Finally, they imply that the state monopoly of foreign trade should end, and Cubans should be free to import all they can afford from abroad.

Tito in Cuba

Like all of the regime’s opponents, the nascent critical left — mostly composed of anarchist and social-democratic currents — has had to operate under close state monitoring and repression. These left-wing formations resist reductions to state benefits and — unprecedented in the Cuban left’s history — call for a worker-managed economy.

Interestingly, they never mention democratic planning or coordination among economic sectors. As a result, their version of worker self-management would create an economy of self-sufficient firms in competition with each other. This resembles the system implemented in Tito’s Yugoslavia from the 1950s until the 1970s.

This market socialism was locally self-managed, but regionally and nationally controlled by the League of Communists. It did increase worker input, decision-making, and productivity at the local level but, because of its competitive and unplanned nature, also created unemployment, sharp trade cycles, pay inequality, and notable regional disparities that favored the northern republics.

The workers’ powerlessness to decide on anything beyond what happened in their workplaces encouraged parochialism, isolating them from broader, national economic decisions. Workers felt no reason to support investment in other enterprises, particularly those located far away.

In the last analysis, as Catherine Samary points out in Yugoslavia Dismembered, Yugoslavian self-management could not confront either the bureaucratic plan or the market. The 1970s was the last decade of growth. Eventually a $20 billion debt led to the International Monetary Fund’s intervention.

The Yugoslav model is a fraught one to emulate in Cuban, then. Further making any kind of worker control unlikely, none of the government’s left-wing opponents have explained how it might be implemented in the absence of a workers’ movement or how it might operate if workers aren’t motivated to fight for those goals.

There are other voices on the critical left that reject any concession to private enterprise and capital on the grounds that capitalist enterprise by definition contradicts socialism. But they have been unable to answer the critical question of how a socialist and democratic Cuba could emerge from poverty and economic stagnation without concessions of any kind.

What is Possible

A growing number of Cubans on and off the island, see socialism — whether democratic or authoritarian — as an impossibility. A diminishing number of Cubans still regard it as either desirable or likely. Certainly, the island’s current economic conditions — combined with extraordinarily powerful international capital — make it hard to imagine a fully fledged form of socialism.

This view derives from a specific application of the general Marxist theory that rejects the possibility of socialism in one country, particularly when that country is economically underdeveloped and exists in a capitalist world currently unthreatened by socialist revolutions.

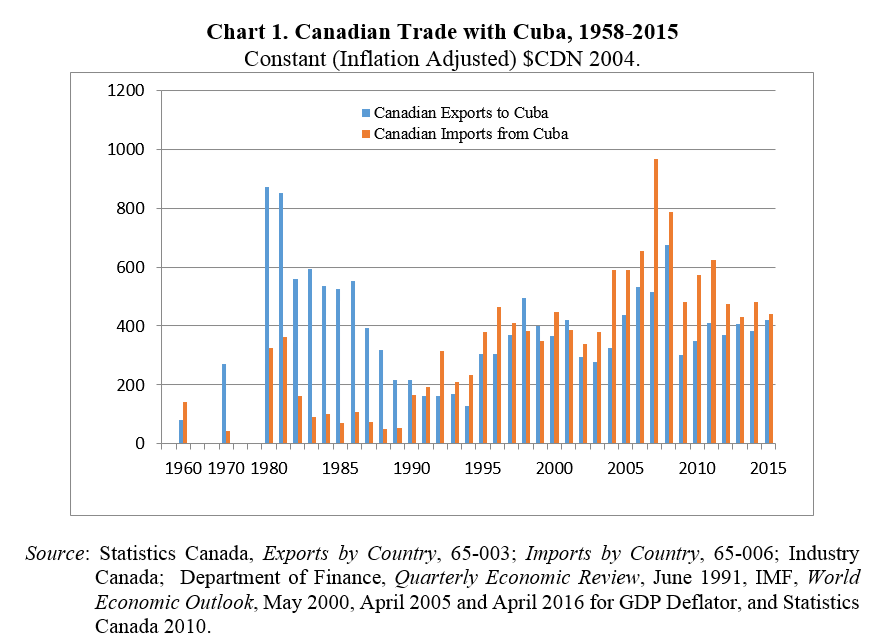

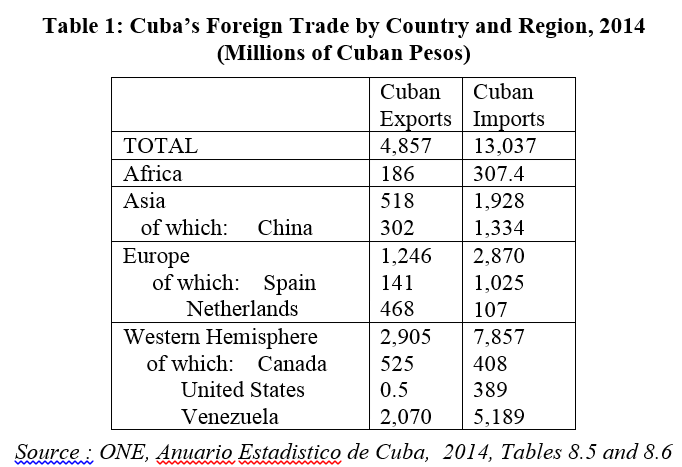

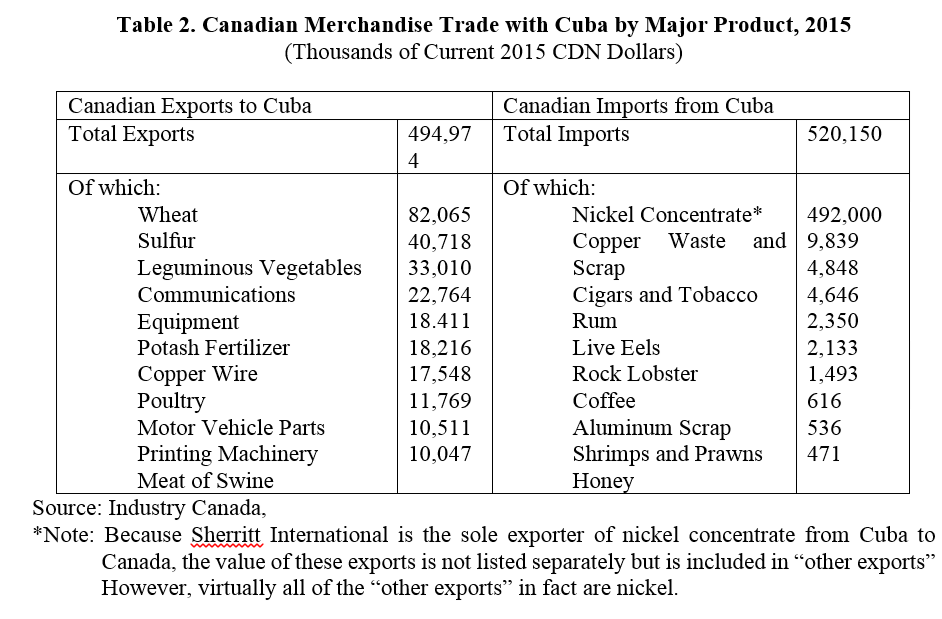

Besides having to face the hostility of its imperial northern neighbor, autarkic “socialist” economic development won’t fit for Cuba because the country still depends on oil imports. Further, its reliance on tourism and medical service, nickel and, to a lesser degree, pharmaceutical product exports and the dramatically shrunken sugar industry underline the foreign-trade character of Cuba’s economy. The island’s considerable integration into the capitalist world market prevents the establishment of a full socialist democracy.

This does not mean, however, that Cuba should abandon socialism. Instead, critics must think in terms of a transitional economy, a holding operation that can realistically be implemented until an international situation more favorable to socialism develops.

Classical Marxist political economy provides a model for what that possible holding pattern could be. This theory recognizes the greater role that individual, family, and small-scale production and distribution play in less-developed economies like Cuba.

In Socialism: Utopian and Scientific, Friedrich Engels distinguishes between modern capitalism — where production is a social act, but the social product is appropriated and controlled by individual capitalists — and socialism — where both production and its appropriation are socialized. Following this distinction, the productive property requiring collective work becomes the proper object of socialization, leaving aside individual and family production as well as personal property.

A transitional economy in Cuba would therefore allow for small, productive private property. This accommodation derives from a fundamental Marxist analysis of capitalism, not an opportunistic adaptation to liberal, free-market politics.

In Cuba, as in many other less developed countries, a transitional economy would subordinate a private sector of small enterprises ruled by market mechanisms under a commanding state sector that administers the island’s big industry — pharmaceuticals, tourism, minerals, and banks — through workers’ control and democratically coordinated and planned in a democratic polity. The government would strive, through its knowledge of market conditions and adequate economic forecasts, towards harmonizing the state and self-employed economy according to a definite plan.

Economic Obstacles

But we must first honestly assess the Cuban economy, which, even before a reduction in Venezuelan oil shipments provoked the current crisis, had been in a marked state of deterioration.

For one thing, its all-encompassing public sector is floundering. As the Cuban economist Pedro Monreal reminded us, the government has openly admitted that 58 percent of state enterprises function “deficiently or badly.”

Also, the island’s economic growth has been generally low, a situation that will only be aggravated by the current crisis. Cuban economist Pavel Vidal Alejandro estimates that Cuba’s GDP will not grow in 2016 and will likely shrink by almost 3 percent in 2017. This would mark the first year of negative growth in the last quarter century.

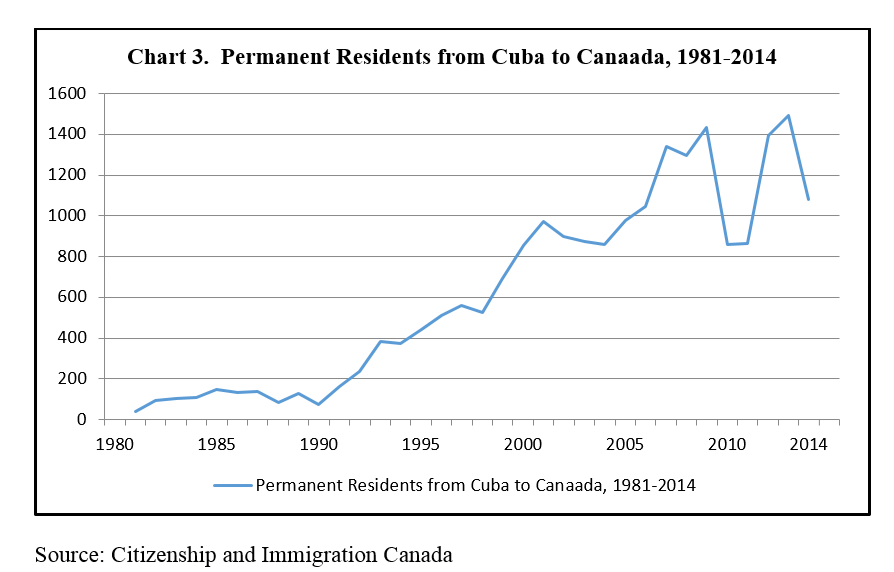

Important voices in the left opposition have argued against economic growth for ecological and other reasons. But improving most Cubans’ material conditions is a condition of a successful democratization. The alternative — continual stagnation and declining living standards — will encourage massive emigration. This represents a tragedy in itself, but would also undermine potential democratic and progressive — let alone socialist — opposition movements.

Alarmingly, the rate of new investment, necessary to replenish the existent capital stock, has become among the lowest in Latin America, dropping below 12 percent of GDP. Government forecasts indicate that investments will fall 17 percent in 2016 and 20 percent in 2017. This will result in a rate of gross capital formation slightly over 10 percent, barely half the rate of investment considered necessary for economic development

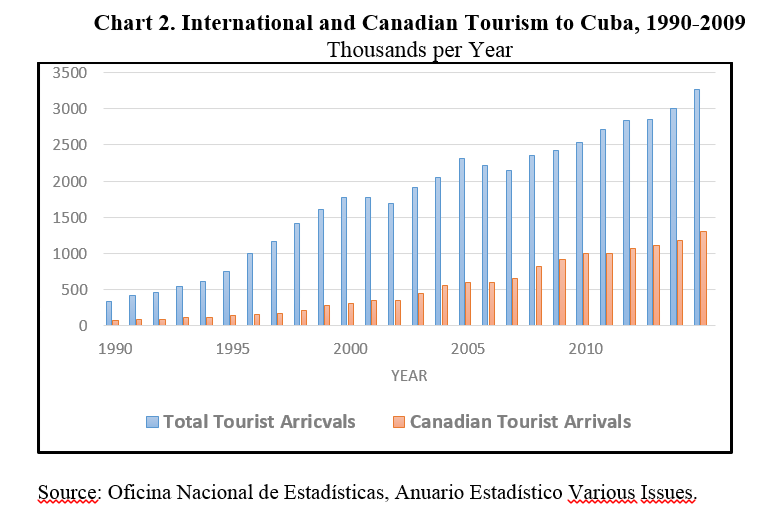

The deterioration of Cuba’s capital stock makes it impossible to maintain the current economic output and living standards, much less to expand them. As a result, the substantial increase in tourism — from 3 million visitors in 2014 to 3.5 million in 2015, and a projected 3.7 million by the end of 2016, sparked by the resumption of US-Cuba relations in December 2014 — has strained Cuba’s tourist capacity to its limit.

Further, President Obama’s elimination of restrictions on the remittances sent to the island by Cuban Americans has significantly worsened food and beverage shortages. Supply cannot meet the increase in demand.

The Cuban economy’s productivity also lags. Agricultural yields — with the exception of potatoes — are well below the rest of Latin America. In industry, biotechnology is the only sector that enjoys high productivity relative to the region.

Rising productivity isn’t just a profit-driven capitalist scheme. An economy that prioritizes reducing backbreaking labor, improving living standards, and maximizing leisure time can only do so if it also prioritizes making more with the existing workforce.

Che Guevara advocated what in effect was the “sweating of labor.” But better organization, technology, and — most importantly — worker control would have the same effect.

Control, in itself, represents a powerful motivator. The current low productivity comes from a bureaucratic system that systematically creates disorganization and chaos and does not provide workers either with political incentives — allowing them to have a say and control over what they do — or with material incentives — typical of the developed capitalist world — to motivate them. Guevara’s moral incentives failed: they were a method to get workers to take responsibility without power and to work harder without control or pay.

Ecological Obstacles

Much of the island’s left opposition to economic growth is grounded in environmental considerations. Cuba now confronts many serious ecological problems, including the increasing number of breakages and leaks in the old and poorly serviced water pipes all over the island. This has led to a massive loss of water, which often spills into streets and empty lots, and to the frequently inappropriate storage that many residents have been forced to resort to in response to the lack of water. Consequently, the Aedes Aegypti mosquito, which transmits the dreaded Dengue illness, has proliferated.

Moreover, the growing number of pigs, poultry, and house-grown crops — part of the much-vaunted, but very problematic, urban agriculture movement — has combined with deteriorating garbage collection services to considerably increase the risk of urban health crises.

The recent government claims to have held off the Zika epidemic and almost eliminated the Dengue fever must be met with skepticism as long as these and other conditions that propitiate the spread of diseases remain.

Anti-growth sentiment among Cuban left-wing oppositionists was reinforced when, on a recent visit to Havana, the economist Jeffrey Sachs recommended that “the Cuban people don’t progress into the twentieth century.” As the left-wing journalist Fernando Ravsberg explained, Sachs argued that Cubans should not forget sustainability and concentrate on the development of organic agriculture, sowed without tractors and grown without using chemical fertilizers or pesticides.

If Ravsberg’s account is correct, Sachs’s argument fails to weigh the relative costs and benefits of environmentally conscious measures. Small and economical tractors, like those the Cuban government is planning to produce in association with US capital, do still consume oil. But oil’s negative environmental effects do not compare to the cost of human- and animal-powered agriculture. The latter model produces less food while requiring massive energy inputs from workers and animals.

Cuba’s history already proves this: the forced abandonment of motorized agricultural vehicles at the beginning of the Special Period constituted, in net terms, a huge setback for the Cuban people.

Also in the nineties, urban transport was demotorized, and many city residents turned to bicycles. They were later abandoned — not because Cubans abstractly preferred the infrequent and overcrowded buses or the expensive urban collective taxis (only a small proportion of Cubans own automobiles), but because bicycles don’t let workers arrive on time from distant working-class suburbs nor do they protect riders from tropical rains and winds from June until November.

The Chinese government has encouraged individual car ownership, which has contributed to the country’s overwhelming urban pollution. This should serve as a warning sign for Cuba to aim for the adoption of an effective mass transit system as an alternative environmental policy.

Finally, at a minimum, Cuba needs to improve on the 5 percent of its electricity derived from renewable sources, which is a quarter of the Latin American average.

The Politics of a Socialist Alternative

The move toward a socialist society does not only require a program, but also a politics. This requires using principled strategic and tactical considerations to engage with the government’s and various oppositionist currents’ proposals.

In doing so, Cuban socialists might find areas of overlap with the liberal Catholic and social-democratic critics. Those include proposals that would promote agricultural production and productivity, such as codifying individual farmers’ usufruct rights, eliminating the compulsory sale of agricultural produce to the government at prices dictated by the Acopio, and creating wholesale markets for small firms and individual producers.

In the field of urban employment, these proposals include forming cooperatives based on the initiative of interested workers, rather than on government diktats trying to dispose of so-called lemons — unprofitable enterprises or businesses that are difficult to administer on a centralized basis, like small restaurants.

At the same time, this new left will need to counter other proposals from those same groups. For example, they call for legalization of all forms of self-employment, including occupations that should be run on behalf of the public interest, like education and medicine.

The Left can respond to the call for free importation by arguing that a democratically run state should allocate foreign exchange on a strict priority basis, with social criteria that favor the most economically deprived sectors of the population and the purchase of capital goods that would most support the country’s economic development. Otherwise, affluent Cubans might waste the country’s relatively scarce foreign exchange on frivolous imports, such as expensive vehicles or luxurious furniture and household effects.

Socialists should also resist the dominant view — held by both critics and an increasing number of government economists — that the government should subsidize people, not products, that it should replace its universal subsidies with a system that provides for only the neediest citizens.

To be sure, those universal subsidies unnecessarily benefit wealthier Cubans. However, the critics of this program never mention their proposal’s downside, which is that it undermines social solidarity. International experience has shown that income-tested programs for the poor produce stigmatization and, as a result, lose political legitimacy over time, thus threatening their long-term funding and viability.

One answer to this problem would be the introduction of a sliding scale where everybody benefits in inverse proportion to their income. This would recognize differential need while maintaining maximum political support.

Socialists in the Marxist tradition understand that subsidies must be selective: if, under current conditions, everything was provided free of charge or sold below production costs, an economy would collapse in short order. Moreover, a relatively underdeveloped economy like Cuba’s has a much smaller surplus to leverage for free and subsidized goods.

But keeping the idea of universal subsidies alive leaves the road open for their future expansion as the Cuban economy becomes more productive and wealthier.

Liberal critics and the government itself support foreign investment as a means to deal with the Cuban economy’s undercapitalization. Many on the Left have opposed it, seeing it as the Trojan horse of capitalism and foreign domination. However, a policy of controlled and selective foreign capitalist investment is indispensable in the absence of a domestic developed-goods industry. These imports could bring in new machinery and renew transportation and utility infrastructure.

New investments from abroad can also have significant employment and multiplier effects that trigger the development of entirely new industries that complement and further develop the established ones.

Further, the impact of foreign investment on wages and working conditions could be negotiated by independent unions, which, among other things, should prioritize the immediate abolition of the Cuban government’s practice of collecting salaries owed to Cuban workers from foreign investors and then turning over to their citizens only a small fraction of the money collected. The government claims that they do this to finance social spending and other government operations. But the same goal could be achieved through a transparent and equitable tax system rather than through the government monopoly of the sale and control of labor.

It is true that worker-controlled production and powerful unions may deter foreign investment. However, an honest public administration and tax system as well as the existence of natural and human resources not reproducible elsewhere can also serve as a draw that supersedes those disadvantages.

Right-wing critics and oppositionists play down — if not ignore entirely — the crucially important issue of Cuba’s growing inequality. For the Left this presents a unique opportunity to push for independent unions, which, along with a progressive tax system, could be a more effective policy than the current one, in which the proliferation of bureaucratic rules harasses small firms and the self-employed.

This is not to do away with regulation entirely; it is necessary in occupational safety, health, pensions, and union rights. If these rules were administered — under worker control and supervision — by professional organizations rather than by a central bureaucracy, they would surely benefit workers, not owners. But to do so will require distinguishing between rules designed to protect the interests of the workers and those that protect the interests of bureaucrats.

Engaging with the specific proposals put forward by both the undemocratic government and by the pro-capitalist opposition sector, the Left will have the opportunity to formulate specific demands and to mobilize people to fight for them. This would build a movement — or at least a clear organizational pole — in spite of government repression and popular skepticism.

Cuba’s present regime will not permit the existence of other legal political parties, independent unions, or a free mass media. Of course, these elements constitute precisely the political setting that would facilitate the kind of transitional social and political system outlined here.

Nevertheless, the left opposition must talk about an alternative model that openly acknowledges both the possibilities and the difficulties involved in building a socialist democracy. This empowers people, rather than making them feel that nothing can be done to push the country in an anticapitalist, radically democratic, and socialist direction. But there is an alternative.