By Geoff Thale and Teresa Garcia Castro

Washington Office on Latin America, (WOLA), February 26, 2019

Original Article: Cuba’s New Constitution

On February 24, Cubans went to the polls to vote on the ratification of a new constitution, one that makes significant changes to the country’s political, social, and economic order. This was the first time in 43 years that the Cuban people had the opportunity to express either support or opposition to a proposal that fundamentally restructures aspects of the Cuban economy and political system.

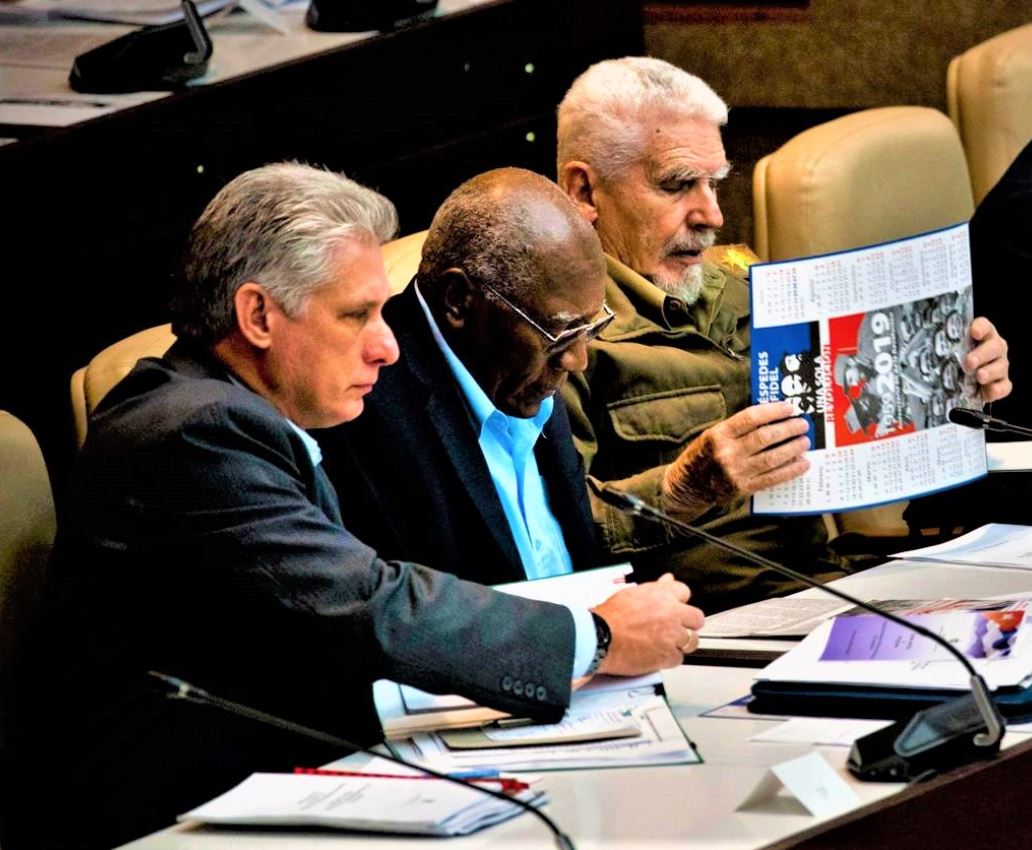

Cuba’s President Miguel Diaz-Canel, left, Cuban First Vice President Salvador Valdes Mesa, center and Cuban Vice President Ramiro Valdez, right.

Cuba’s President Miguel Diaz-Canel, left, Cuban First Vice President Salvador Valdes Mesa, center and Cuban Vice President Ramiro Valdez, right.

According to the Cuban electoral commission, voter turnout reached 84 percent (slightly higher than in Cuba’s last election cycle in April 2018), with 87 percent of the votes in favor. The size of the vote suggests that, whatever misgivings or frustrations Cubans had with the new Constitutional proposal, they saw it as a step in the right direction.

The new Cuban Constitution retains language that proclaims the Communist Party’s guiding role in Cuban society and socialism as being irreversible. At the same time, the document includes several major changes to Cuba’s traditional economic and political model.Additionally, the drafting process that yielded the final text that was approved in the February 24 referendum involved a citizen consultation process that was relatively inclusive and even resulted in changes to the final document, an important indication that the Cuban government’s gradual process of reform is continuing.

Overall, there was real and relatively open debate leading up to the referendum on the Cuban Constitution.

Cuba’s current constitution was drafted and approved by referendum in 1976. Since then, the government’s vision for the country’s economy has changed significantly, especially in the past decade. Reform guidelines announced in 2011, alongside a Communist Party document approved in 2016, make clear that Cuba is moving toward a mixed economy that includes both a private sector and state-run sector, a more significant role for foreign investment, and where the central planning role, though not eliminated, is diminished. A small private sector has already emerged in Cuba, and grown substantially in the last few years.

Overall, the past decade has seen Cuba’s Communist Party shift (at least in principle) toward a less heavy-handed approach to exercising influence over both Cuban society and the economy. In addition, expanded internet access has helped spread access to information and enabled greater and more open political debate.

In the face of these ongoing changes, the government launched a process to revise and update the 1976 Cuban Constitution. Some people had hoped that the final text would incorporate more radical changes in the Cuban model, and were disappointed. Indeed, some rumored changes did not appear in the final version that was voted on, while other proposed reforms appear to have been postponed to later debates about implementing legislation in the National Assembly.

Still, Cuba’s new constitution includes some noteworthy overhauls.The document does the following:

- Recognizes private property and promotes foreign investment as fundamental to the development of the economy.

- Limits the term of the president—who is selected by the National Assembly, as in parliamentary systems—to two consecutive five-year terms, and requires that the president be under sixty when s/he is elected. (This is a dramatic change from the era in which aging revolutionaries monopolized key government positions, and were repeatedly approved in their positions.)

- Restores the pre-1976 position of Prime Minister, an official selected by the president who leads government ministries on a day-to-day basis.

- Forbids discrimination based on sexual orientation.

- Guarantees women’s sexual and reproductive rights and protects women from gender violence.

- Establishes the presumption of innocence in criminal proceedings and the right to habeas corpus.

- Strengthens the authority of local governments.

- Allows holding dual citizenship.

These changes, and others, will have to be implemented through legislation and regulation. That process is likely to be both gradual and complicated. However, the changes in the new Cuban Constitution are undeniably significant, both reflecting and advancing the process of economic reform, strengthening citizen protections, and making the political process more transparent. While not as transformative as some had hoped, they should not be dismissed as meaningless or cosmetic.

THE CONSTITUTIONAL PROCESS

The process by which the new constitution and referendum came about is also noteworthy, given the degree of citizen participation involved and the government’s response to some of the feedback it received.

Constitutional reform had been under discussion since 2013, but it wasn’t until June 2018 that a drafting commission (made up of senior government and Communist Party officials, the heads of several Cuban National Assembly committees, and academic and technical advisors) began to work on this issue seriously. The government, the National Assembly, and the Communist Party all engaged in ongoing internal debates about the draft constitution, reflecting a larger national conversation among political elites about the pace and depth of political and economic reform in Cuba

Despite Cuba’s image as a state that has suppressed religious freedom, prevented organized political campaigns, and been unwilling to listen to citizens’ views, the government responded.

The first draft of the constitution was approved by the National Assembly in July 2018. For a subsequent three-month period, Cubans were invited to suggest changes to the proposed draft. According to official numbers, more than 8 million people participated in nearly 112,000 debates in workplaces, schools, and community centers, and suggested a large number of proposed modifications to the constitution draft.

This participatory process was also significant in that, for the first time, Cuban expats were allowed to submit proposed changes to the constitution draft. However, other than diplomats, Cubans abroad were not allowed to vote in the referendum unless they returned to the island to cast their ballots.

Overall, the consultation process constituted a significant exercise in citizen participation. While officials were not required to make changes based on citizen feedback, there were some cases in which they did.

The most well-known example of this was the same-sex marriage provision: a draft of the constitution originally included language that defined marriage as a consensual union between two people, without specifying genders. This attracted significant pushback from evangelical churches and some sectors of the Cuban Catholic Church, who organized a campaign to get the provision withdrawn. Many Cubans supported this campaign and made their objections known by disseminating posters, stickers, and t-shirts, threatening to vote “no” in a constitutional referendum. Around 179,000 people signed a petition, backed by evangelical churches, calling on the government to withdraw the provision.

The new constitution and the constitutional drafting process mark important steps forward in the economy, the political system, and the decision-making process in Cuba…

Despite Cuba’s image as a state that has suppressed religious freedom, prevented organized political campaigns, and been unwilling to listen to citizens’ views, the government responded. The commission in charge of processing citizen feedback eventually withdrew the proposed language. The just-approved constitution now contains no language on marriage; the issue will likely be revisited in a debate over the Cuban Family Code sometimes in the next two years.

Meanwhile, the government launched a campaign to encourage “yes” votes with posters, advertising, and the use of social media. On the other hand, opposition forces also painted “no” signs, printed up T-shirts, and staged Twitter protests. While there were reports that some proponents of the “no” vote were harassed, overall, there was real and relatively open debate leading up to the referendum on the Cuban Constitution.

WHAT HAPPENS NEXT

Overall, the new constitution and the constitutional drafting process mark important steps forward in the economy, the political system, and the decision-making process in Cuba, and should be understood as signs of change in the thinking of the political leadership and in the population as a whole.

Indeed, the referendum comes at a complicated moment for Cuba. Economic growth has stalled in the past year, and is projected to be no more than1.5 percent in 2019. Austerity measures initiated in 2016 will continue this year, including cuts in energy and fuel to state companies and reduced imports of consumer goods. The government will struggle to maintain its investment in the social safety net, including free healthcare, education and other services

Meanwhile, the Trump administration is threatening additional economic sanctions on the island, which could make foreign investment riskier. These sanctions will damage Cuba’s already fragile economy, and hurt everyday Cubans. In addition, they are likely to discourage the process of economic reforms and will have a negative impact on the growing private sector. A more constructive approach, and one that would encourage rather than discourage internal reform, would be to return to normalizing U.S.-Cuban relations. Ultimately, recognizing that important if gradual changes are underway in Cuba—as the new constitution illustrates— is in the interests of both the Cuban people and the United States.