Would the island nation’s sports regime retain autonomy or become a sports colony?

By:Morgan Campbell Staff Reporter,

Toronto Star, Published on Thu Dec 18 2014

Original article here: Baseball

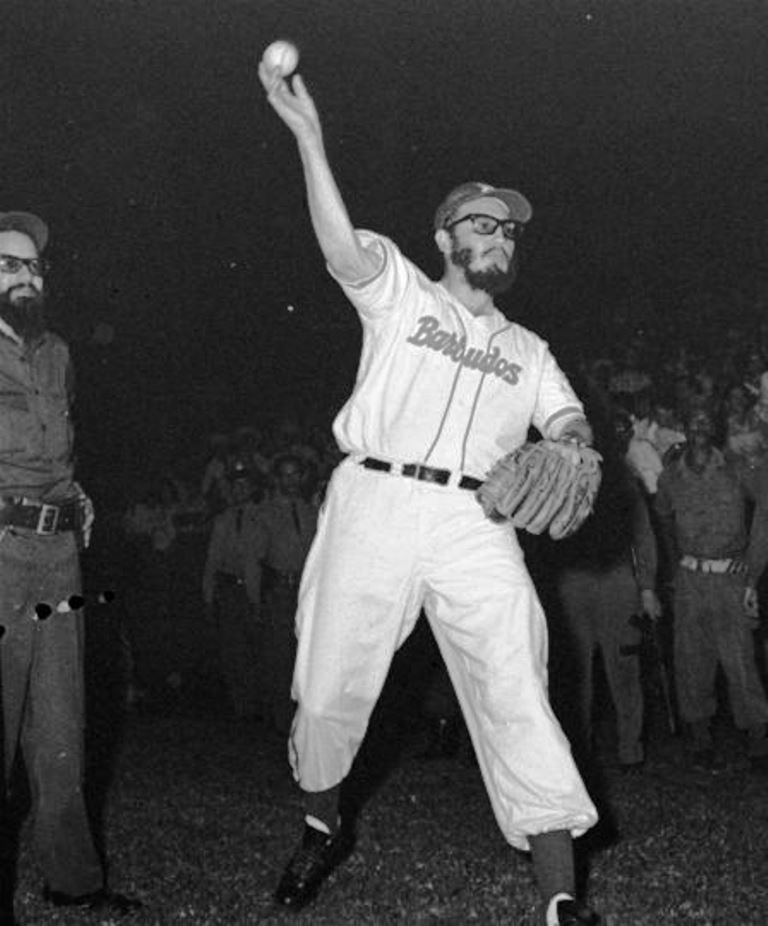

The Associated Press file photo; In 1959, a rebel solider from Fidel Castro’s army holds the bat of Detroit catcher Charley Lau, who was playing ball in the Cuban winter league in Havana.

The Associated Press file photo; In 1959, a rebel solider from Fidel Castro’s army holds the bat of Detroit catcher Charley Lau, who was playing ball in the Cuban winter league in Havana.

Thursday afternoon in Miami, Gilberto Suarez was convicted for his role a human trafficking operation that smuggled baseball sensation Yasiel Puig out of Cuba in 2012. Puig had agreed to pay Suarez 20 per cent of his future earnings, but the price went up when the Mexican drug cartel working with Suarez also demanded a cut.

Suarez now faces up to a decade in prison, while Puig is headed into the third season of a $42 million (U.S.) contract with the Los Angeles Dodgers.

And the underground economy that prompts drug gangs to spirit star athletes out of Cuba — where pro sports have been illegal since 1961 — will crumble if the ends a five-decade embargo of the island.

But beyond shutting human traffickers out of pro baseball, Wednesday’s announcement that the U.S. and Cuba would move to normalize relations signals a massive shift in Cuba’s role in the global sports-industrial complex.

Cuba’s sports system has spent the last half-century focused on Olympic success. But as a return to professional athletics becomes possible, it’s not clear if Cuba will profit from participating in free-market sports or become colonized by wealthy U.S. outfits seeking discount talent.

The issue is especially pressing for Major League Baseball, where 25 Cuban-born players made rosters in 2014. That Cuba trails only the Dominican Republic and Venezuela as a source of foreign players, highlighting the depth of talent there. Major League teams aren’t authorized to scout Cuba, and players have to leave the country before they’re eligible to sign contracts.

Baseball industry experts say Major League Baseball needs to reach a detailed agreement with Cuban baseball officials on how to scout and sign players. An unfettered free market would favour big-spending teams like the Yankees, while a draft for Cuban players would help small-market teams keep pace.

Neither system necessarily benefits Cuba’s sports infrastructure.

“It’s (similar to) colonialism, and this is precisely what the Cuban government will want to avoid,” says Adrian Burgos, professor of Latino Studies and sport history at the University of Illinois. “There’s a lot of state resources invested in developing those players . . . It’s easy to say ‘We’re Major League Baseball and this is how it’s going to happen,’ but Cuba has its own baseball tradition.”

MLB faced a similar situation in the late 1940s and early 1950s, when the toppling of the colour barrier opened up a previously untapped talent source. Big league teams signed African-American stars like Jackie Robinson and Larry Doby, but weren’t obligated to compensate the Negro League teams that developed them.

Integration enabled MLB’s current cultural diversity, but a decade-long drain of star power crippled Negro League teams financially, leading to their eventual collapse.

If Cuba wants to guarantee its 16-team domestic league remains viable, Toronto-based sports lawyer Arturo Marcano says it should emulate the Japanese league, which requires MLB teams pay a posting fee before negotiating with a player.

“The Japanese model would allow them to have some control over players, which is something really important for them,” says Marcano, who also writes a baseball column at ESPNDeportes. “The Cuban government will welcome the income they get from signing players, regardless of the system they adopt.”

Baseball wouldn’t be the only sports business facing changes.

In 1976, Cuban superheavyweight boxing legend Teofilo Stevenson won his second Olympic gold medal and entertained intense speculation that he would defect from Cuba for a big money showdown with Muhammad Ali. But Stevenson wouldn’t leave Cuba for capitalism. “What is $1 million compared to the love of eight million Cubans?” he’s often quoted as saying.

But for the past two decades, top Cuban boxers have trickled out of the country to fight professionally, and right now four Cuban fighters hold pro world titles.

When Cuban Guillermo Rigondeaux dismantled Nonito Donaire in April 2013, he figured that the win over an established star would propel him into boxing’s economic elite, where eight-figure paydays are the norm.

But no high-profile fights have materialized, and many observers blame the free market. As a Cuban exile, he doesn’t have a built-in U.S. fan base, while his cerebral fighting style isn’t exciting enough to attract casual viewers.

Rigondeaux’ manager, Gary Hyde, fumes over the idea that Cuban boxers are bad for business, and sees a huge opportunity if the U.S. and Cuba can normalize relations. Staging a title bout in Cuba, he says, will disprove the notion that Cuban fighters can’t attract customers.

“They reason they haven’t a fan base is because there are 11 million people in Cuba and they can’t get out to see” Cuban fighters compete), says Hyde. “Put those fighters in a baseball stadium in Cuba and I guarantee that stadium would be full . . . But I obviously wouldn’t be charging $2,000 for ringside seats.”

Wednesday’s announcement from the White House spurred similar speculation among baseball observers, who floated the idea that MLB could eventually expand to Havana.

Big league teams have set up shop in the Caribbean before.

From 1954 to 1960, the Havana Sugar Kings served as the Cincinnati Reds’ top farm team, and in 2003 the Montreal Expos played 22 home games in Puerto Rico. “Latin America is a market (where) MLB wants to have fans,” Burgos says. “It’s so much closer than Japan.”

Carleton University economist Archibald Ritter says Havana’s Pan American Stadium could host big-league baseball, but cautions that a franchise also needs deep-pocketed ownership, corporate support and a fan base with time and money. That’s where Havana would struggle.

Ritter, a research professor who studies the Cuban economy, says the best ownership option would involve the government collaborating with a foreign corporation, but that Cuba would also need to solve its currency dilemma. Last year, the country moved to phase out the “convertible peso,” a currency equal in value to the U.S. dollar — about 20 times the value of the standard Cuban peso aimed at tourists and tourism-industry workers. Most Cubans are paid in standard pesos and many work off-the-books jobs to hustle convertible ones.

Ensuring Cubans have the purchasing power to attend commercial sports events would mean settling on a single, strong currency. In 2010, Cuba’s per capita GDP was $10,200, according to the CIA World Factbook. That figure is about a quarter of Canada’s per-capita GDP but still strong enough to enable a team to sell low-cost tickets.

“The players would have to be paid something close to what they would get in the U.S., so it would have to be a convertible currency,” Ritter says. “If enough Cubans could pay a reasonable cost — not an American cost — to pay a game, then I think it could become possible . . . If a ticket were $15 or $20, Cubans would go. They could afford it.”