By Sarah Rainsford; BBC News, Havana

Havana risks seeing its historic city centre reduced to ‘a void’

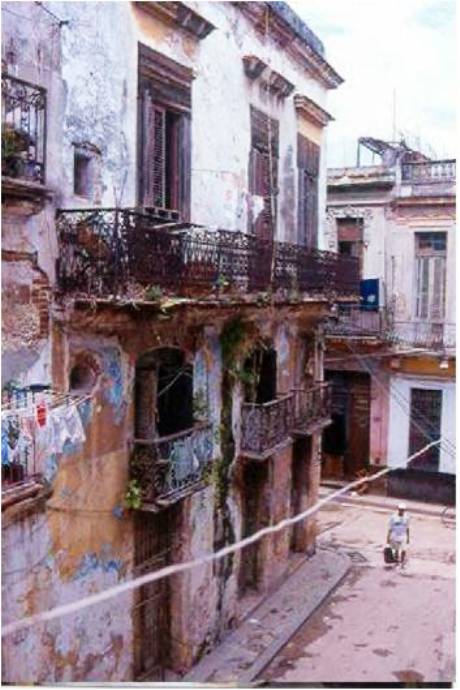

Havana is beguiling from a distance, especially its old colonial buildings bathed in tropical sunshine. But up close this city is crumbling. Number 69 on the Malecon, the city’s long seafront, looks particularly perilous. The apartment block has gaping holes where chunks of brick and plaster have fallen away. Bare metal rods protrude where balconies used to be.

“Look how badly these columns have deteriorated,” says Olga Torriente, pointing to thick cracks in the external wall of her flat, up on the top floor.

She pulls her bed into the centre of the room in a storm, afraid the whole wall could come crashing down. Big chunks have already fallen off this building on the Malecon Some of Olga’s neighbours – those judged priority cases – have been rehoused. Others joined a “microbrigada”, or construction team, almost three years ago to help build a replacement apartment block for themselves. But there is still no completion date, and no alternative.

“How long will we have to wait? We need to get out,” says Ms Torriente. “People ask me if I’m not afraid to live here. Of course I’m afraid, but this is my house so where can I go?”

Like Ms Torriente, most Cubans own the house they live in – one of the principles of the revolution. But many have lacked the funds to maintain them.

Adding to Cuba’s difficulties, some 200,000 families across the island were left homeless by devastating hurricanes in 2008.

“Buildings are crumbling because they’re old. Then there’s the salt spray, humidity, termites, hurricanes and overcrowding. There are many kinds of problems and sometimes altogether,” explains former city architect Mario Coyula.

Seven out of every 10 houses need major repairs, according to official statistics. Some 7% of housing in Havana has formally been declared uninhabitable. The province around the capital needs some 300,000 more properties. The shortage has forced expanding families to build lofts and new partitions within their homes, putting weakened structures under additional strain.

“It’s difficult, because neither the government nor the people have the money to care for the buildings. In a way, we inherited a city we are not able to keep,” Mr Coyula says, referring to Havana’s once grand colonial-era architecture in particular.

But the government is now trying to stop the rot – literally. For decades, Cuba subsidised all construction materials, but production slumped when state budgets became strained. Finding materials was difficult and an expensive black market emerged. There were also tight restrictions on building work.

Now, Cuba has shifted tack. It is allowing builders yards to sell materials at market prices, while offering state funds to help those home owners in most need. Hurricane victims are a priority but anyone on a low income and in what is considered “vulnerable” housing can apply.

“We used to subsidise materials now we’re subsidising the individual,” says Marbelis Velazquez, from Havana’s provincial housing office. “Not everyone is in the same situation, economically and the state clearly has to help those most in need,” she says.

The new grants range from 5,000 Cuban pesos ($208) for minor repairs to a maximum 80,000 pesos ($3,333) to build a 25 sq metre room from scratch.

In Cerro, one of central Havana’s most run-down districts, the Padro family is hoping their own petition will be accepted. Nadia Padro’s parents built a basic wooden and brick shack in their garden when living there with six siblings and assorted partners and grandchildren became too crowded. There is a kitchen, with water and electricity. But the roof leaks when it rains and Nadia and her husband have to squeeze into one bed at night alongside their two young children. “A government grant would really improve things,” Nadia says, explaining that they want to build a separate room for their daughters. Neither she nor her husband has a steady job and could never afford the work on their own.

The government plans to fund the grants with the sales tax it collects from state-owned building yards. It has already increased production and after years of bare forecourts, the yards are filling up with materials for sale.

“Before you had to hunt for things through friends or contacts,” Hernan Mayor explains, as he loads roofing material onto the back of his bike at The Wonder builders yard. He has been saving money to build a small extension to his house. “The materials are all here legally now, which is better. If things were a bit cheaper, it would be perfect. But at least they’re available now,” he says.

Nadia Padro is hoping to get a government grant to build another room in her shack New regulations have also made it much faster – and simpler – to get a licence for new building work. And, for the first time, bank credit is becoming available.

So Cuba is creeping into action over its housing stock. But the delay has already cost dearly. In Havana alone, it is said that three houses collapse either partially or completely every single day.

As for the city’s heritage, beyond the carefully restored “hub” of Old Havana, much of that may already have been lost for good. “It’s impossible to preserve all the buildings, I know many will go,” says s architect Mario Coyula. “If nothing changes, Havana may end like a circle…with a void in the middle where the city used to be.”

Pingback: Aktuelles aus der Wirtschaft in Kuba | Cuba heute