October 27, 2013 |

HAVANA TIMES — Antonio Castro, son of Fidel Castro and team doctor of the Cuban baseball squad, requested that the Cuban players who fled the island and became professionals in the US Major Leagues be allowed to play with the national team in international tournaments, reported dpa news on Sunday.

“We need to change on both sides, we have to do something realistic, we have to do something for our players … [The current policy is] not good for athletes, for families, for anyone. We lost those players but why can’t they return to play again with the national team,” asked Castro, in an interview on Cuban baseball today by ESPN.

“We have to strive to not lose them. Unless we change, we lose the players, we lose everything,” he added.

Up to 16 players who fled the island played this season in the Major Leagues, including the new idol of the Los Angeles Dodgers, Yasiel Puig.

Professional sports were abolished on the island in 1962, prohibiting Cuban athletes from working as professionals or joining foreign teams. Over the years it became routine for some athletes to skip out during trips abroad to try to build a future as professionals.

The sacrifice of having to leave their family is sometimes compensated with millions: This month Cuban first baseman José Dariel Abreu closed a record contract for a non-US player to play next season with the Chicago White Sox. He will earn US $68 million over six years.

Abreu defected from the island in August and obtained residency in Haiti, from where he began processing permits with the US Treasury Department in order to be a free agent and sign with the majors.

From Haiti he traveled to the Dominican Republic, where major league scouts were able to follow his progress as he trained.

Antonio Castro noted as an example the visit to Cuba this year by Jose Contreras, who defected and returned to the island after spending ten years playing in the United States. “I never expected to return to Cuba because many before me were not able to return, since the government considered us traitors,” he told ESPN.

Contreras escaped from the island in 2002 taking advantage of the presence of the national team in Monterrey, Mexico.

The return of the pitcher early this year was the first by an athlete who had abandoned a national team and came after the new Cuban immigration policy took effect on January 14, which allows for the return of athletes who left the country through irregular channels since the early ’90s and later as long as they had spent eight years abroad.

“Many want to go back and live here to teach children, is that bad? No, of course not. Contreras returned and is working for children to develop baseball. I love that idea,” Antonio Castro told the ESPN reporter in English during her recent visit to Cuba .

The island seems to be gradually lifting restrictions for high-level athletes that have existed for decades. The Cuban authorities, for example, announced on September 27 that they would allow their athletes to sign in the off season with teams in foreign leagues as long as they play in the Cuban leagues.

The reform seeks to “generate revenue” and “gradually increase wages,” explained the official daily Granma.

The measure is part of the process of market economic reforms being instituted by Raul Castro’s government.

In July, the Cuban Baseball Federation also announced that it had authorized the signing of active Cuban ballplayers with professional clubs abroad with the aim of “inserting Cuban baseball in the world.” Shortly after the authorities allowed the three players to sign with the Mexican professional team the Campeche Pirates.

“Cuba needs change, we are part of the world, we need to change,” Antonio Castro told ESPN.

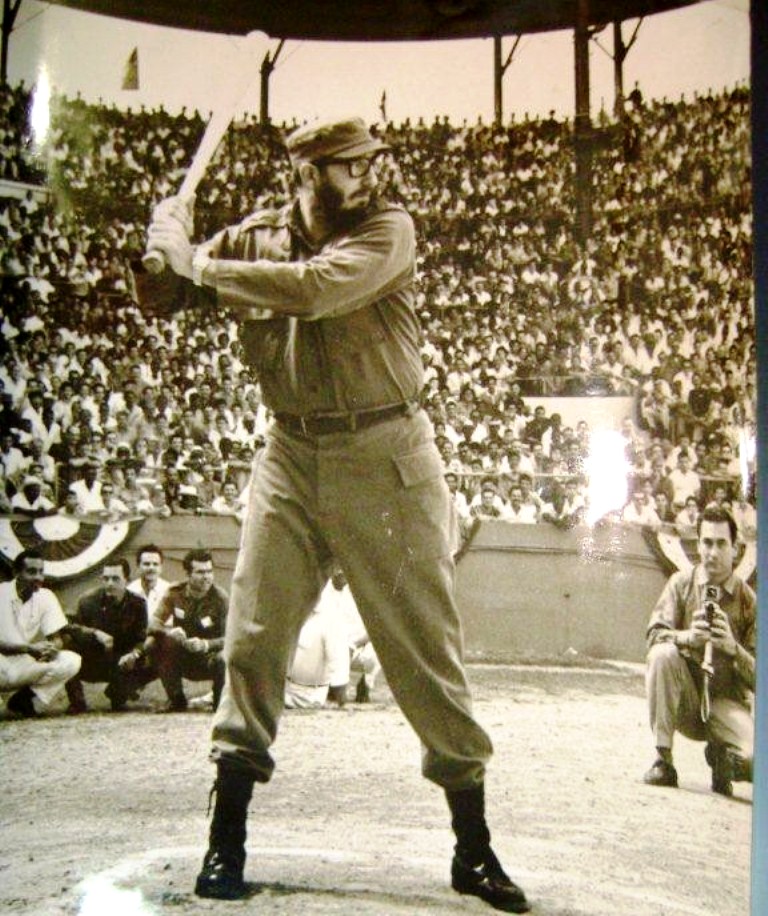

Antonio Castro’s Father in Earlier Times

Antonio Castro’s Father in Earlier Times