Original Essay Here: 19 November 2012. BY BRIAN LATELL. The Miami Herald

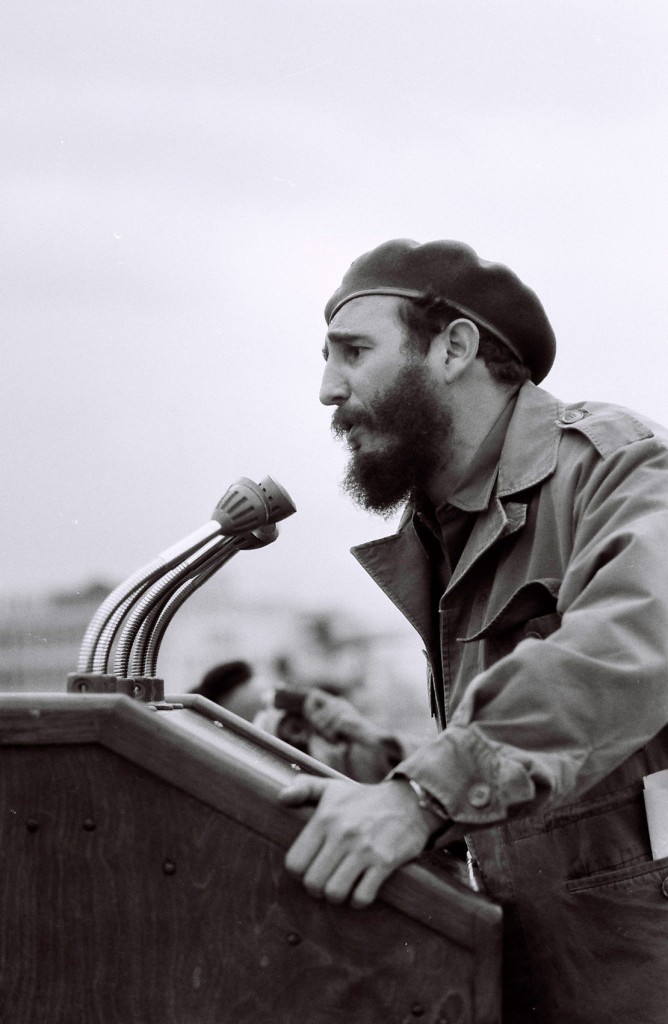

He spoke on the public record more than any political figure in history. It is a strange and dubious distinction to be sure. But during 48 years in power Fidel Castro elevated public discourse into a form of narcissistic excess unlikely ever to be exceeded.

He holds the record for the longest speech ever delivered at the United Nations. In September 1960 he droned on for four and a half hours, excoriating Richard Nixon and John F. Kennedy then in the final weeks of their presidential campaigns. Kennedy got the worst of it; he was, Castro seethed, “an illiterate, ignorant millionaire.”

Five- and six-hour orations were standard fare during the early years of Castro’s revolution, with him often appearing in public places before vast crowds or in broadcast studios several times in a single week. His longest known speech lasted an astonishing 12 hours.

Always in uniform, he spoke in dozens of foreign locales — in a Viet Cong-controlled area of South Vietnam, in the Stalinist North Korean capital, and earlier, on a few American university campuses — as well as nearly everywhere on the island when a small crowd could be gathered.

Anti-American tirades, harsh revolutionary incantations, and surprising policy announcements were standard content. Yet Castro will not be remembered for any single galvanizing performance or memorable passage that is uniquely his own. Unlike many great orators he hoped to emulate, nothing he ever said in public has endured as a defining rhetorical legacy.

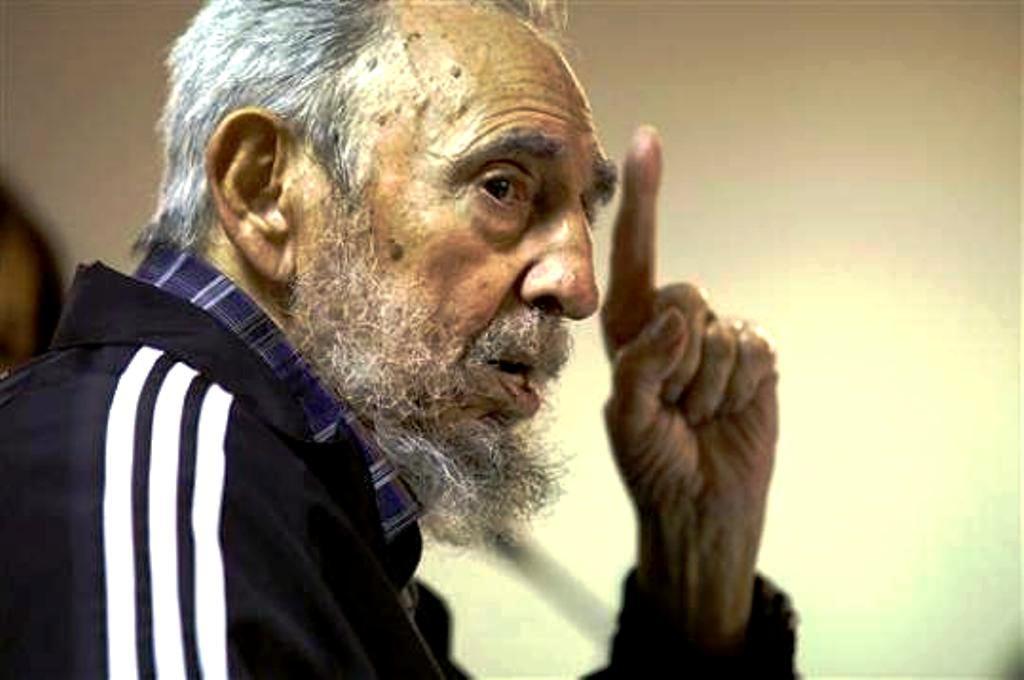

By the time he delivered his last two official speeches —in eastern Cuba on July 26, 2006, before requiring emergency surgery a few days later — he had deteriorated into a frail, scarcely coherent caricature of his earlier self. The strident voice that had uttered uncounted billions of public words fell silent except for a few halting and pitiful appearances on Cuban television.

Yet within a few months after provisionally retiring from the presidency, he resorted to a new form of public communication. Signed “reflections” that he penned, dictated, or directed staff members to compose for him began appearing prominently in the state media. The first of these editorials — a ponderous rumination about global food and water shortages — appeared in March 2007.

Another 450 followed, all of them oddly disembodied and reflecting a distinctly different and diminished Castro. In his semi-retirement he pontificated about lofty and esoteric subjects, almost always international in scope, while continuing to attack American “imperialism.”

Characteristically, he was unpredictable. Raúl Castro, his successor, was hardly ever mentioned by name and never complimented or congratulated. On occasion in fact, he was the subject of veiled criticism for the economic changes he implemented. Few other Cuban leaders were named either. That was in contrast, however, to the numerous accolades heaped by Fidel on Venezuelan president and Cuban benefactor Hugo Chávez.

Yet in his new role, the author Fidel was once roused — or induced — to intervene openly in a delicate internal political dispute. In March 2009 two of the regime’s highest ranking leaders were sacked by Raúl Castro. Foreign minister Felipe Pérez Roque and vice president Carlos Lage were ambitious protégés of the retired Fidel, both thought to be top contenders for eventual power.

So, when Fidel flamboyantly condemned them in a published reflection — they had been seduced “by the honey of power” he wrote — their fates were sealed. Raúl’s position was strengthened as a result and Fidel’s lingering influence highlighted. Reading the tea leaves of what Fidel wrote, and did not, was for more than five years an obligatory task for students of Cuba’s revolution.

When the regime recently announced that Fidel had issued his last reflection it was at least in part for reasons of health. But his absence for the first time in nearly 60 years from the revolution’s revealed dialogue suggests that his successors have crossed an historic Rubicon. Raúl now has a freer hand to advance needed economic reforms, and possibly even to seek improved relations with the United States.

Thus far he has only cautiously departed from the sacred Fidelista policies of the past, constrained by hard liners devoted to his brother and by corruption and bureaucratic intransigence. But as Raúl speaks of eliminating the regime’s history of “paternalism, egalitarianism, and idealism” he means Fidel’s dogmatic policies that now seem likely to be more systematically discarded. After six years at the helm, with his hand-picked team of military and civilian leaders at his side, General Castro can feel more secure.

So, silenced and sidelined for the second time, Fidel will likely now be unable to decisively influence the course of Cuba’s failed revolution. With no fanfare, he will drift into the dark recesses of history.

Brian Latell is senior research associate, Cuba Studies, University of Miami and author of Castro’s Secrets: The CIA and Cuba’s Intelligence Machine.

After almost half a century, out of the game, 2012

After almost half a century, out of the game, 2012