Nacla May 20, 2019

Arturo Lopez Levy, Visiting Assistant Professor of International Relations, Gustavus Adolphus College, Minnesota.

Original Article: Why Trump’s Cuba Policy Is So Wrong

Nearly five years have passed since President Barack Obama restored diplomatic relations with Cuba and began relaxing the U.S. policy of unilateral sanctions. Now, the Trump Administration is doubling down on a failed strategy of hostility, reducing engagement with Cuba, and returning to the 1996 Helms-Burton law, one of the most repudiated pieces of “trade” legislation in the world. Trump’s decision to restore the grip of Cold War-era policy to the Strait of Florida caters not to the interests of the Cuban people, but to a small group of voters between Little Havana and Doral—the new Little Caracas—in South Florida.

On April 17, National Security Advisor John Bolton announced in a speech in Miami that the U.S. would be fully implementing Chapters III and IV of the 1996 Helms-Burton law—which allows U.S. citizens to file claims against Cuba’s trading and investment partners for properties nationalized following the revolution 60 years ago. Bolton salted his red-meat speech with new restrictions on U.S. non-family related travel and remittances sent to Cuba. Present in the audience were veterans of the defeated 2506 Brigade, a group of exiles who invaded Cuba in 1961 after receiving CIA training in Guatemala.

Reparations for Exiles Over Citizens in Need

Under Chapter III of the Helms law, American courts will be open to hear any claims for lost properties by Cubans who became American citizens before 1996 after January 1, 1959. The former Cuban economic and political elites seem poised to try to claim all of these properties—except the one for the responsibility of mismanaging a country to the point of revolution.

It is not the United States government’s responsibility or place to force the current or any future Cuban government to prioritize compensating Cuban right-wing exiles over demands for other reparationsThe implementation of this chapter has profound implications for Cuba’s national reconciliation and how Cubans may perceive Washington in the future. Cuban-Americans who lost their properties as result of revolutionary nationalizations were at the time Cuban nationals, living under Cuban jurisdiction and sovereignty. The logical venue for these Cubans to seek remedy for the alleged injustice committed against them is in Cuban courts. No matter what one thinks about the priorities for reparations for Cuban injustices, it is difficult to argue that U.S. courts are the proper place for solving these issues. It is not the United States government’s responsibility or place to force the current or any future Cuban government to prioritize compensating Cuban right-wing exiles over demands for other reparations, such as for slavery or any of the many other abuses committed in Cuban history before or after 1959. Such meddling in issues of exclusive Cuban sovereignty will not sit well in Cuban politics and will feed anti-American nationalist resentment. Whether Cubans would like to use their own resources to compensate wealthy exiles should not be an imposition of the United States government.

This isn’t the first time that U.S. policy has pressured a Latin American government to put appeasing exiles over its own governance. In post-revolutionary Nicaragua in 1994, Senator Jesse Helms imposed a hold on legislation for U.S. aid, with consequences for the government of Violeta Barrios de Chamorro. A significant portion of U.S. economic aid to Nicaragua for development purposes went to compensating anti-Sandinistas who had lost property or investments under the revolution rather than towards poverty alleviation efforts. Bolton’s support for tightening Helms-Burton to allow similar claims for Cuban exiles is similarly misguided.

Unilateral sanctions will not work in Cuba because other countries will not stop trading and investing if there is a profit to make. After 60 years of conflict and hard sanctions, the Cuban communist regime has survived, outmaneuvering every U.S. president who imposed or implemented sanctions since the Eisenhower era. Even though the U.S. is a much more powerful country than Cuba, it is still unable to impose its preferences on its weaker neighbor. Cuba has demonstrated time and time again that despite this asymmetric power, they are well-versed in strategies to delegitimize the U.S.’s position.

As Wayne Smith, the American diplomat who closed the U.S. embassy in Havana in 1961 and later returned to Cuba as Chief of the Special Interests Section (1978- 1982) once wrote: “Cuba seems to have the same effect on American administrations that the full moon once had on werewolves.” Bolton’s April 17 speech in Florida is simply the same howling. It only makes sense as a policy towards Florida, not towards Cuba.

Under Chapters III and IV of the Helms law, right wing Cuban-Americans are trying to internationalize the U.S. embargo against Cuba at all costs. They have brought legal claims against U.S., Canadian, and European Union citizens and companies. Trump’s catering to these interests by returning to this logic is detrimental to U.S. interests in Cuba and Latin America—and to Cuba itself—for a number of reasons.

Cuba in Transition

First, this decision ignores Cuba’s current moment. Most Cubans are eagerly looking to their first post-Castro president, Miguel Díaz-Canel, to address the critical challenges of reforming the country, especially its economy. While the new president has maintained a clear distance from the most audacious reforms, he is aware that the Cuban Communist Party’s rule is not sustainable without a wider opening of the economy to private business and foreign investment, or improving relations with reform-oriented civil society and diaspora groups. At this critical moment, Trump’s aggressiveness will distract the Cuban public debate from Cuba’s internal situation and create an opportunity for the Communist Party to rally the population and its various elites—old and new, pro-market or pro-state-owned corporations, pro or against regulation—behind the patriotic flag.

The more the Trump administration tries to asphyxiate Cuba, the harder the Cuban government will impose political discipline in its ranks and within Cuban civil society. In contrast, in the wake of Obama’s rapprochement, a wide spectrum of autonomous publications emerged. Although this expansion of the public sphere does not amount to democratization and did not result from U.S. policy, a friendly international environment may have played a constructive role in influencing their development.

Patriotic segments of civil society such as the Catholic Church, the majority of intellectuals, LGBTQ activists, and other groups will condemn U.S. policy towards Cuba. Those who do not close ranks with the government against foreign aggression will appear aligned with what Cuban national hero and poet Jose Martí called “the scrambled and brutal north.” Not a good position to be in Cuban politics, isolated with just one foot out of prison.

Sanctions for Sanctions Sake

Most of Trump’s Latin America team do not understand how political asymmetry works in international affairs. Hard power is tremendously important in state-to-state relations, particularly in war. But in many cases, the stronger cannot impose its preferences on the weaker side. Small countries have agency and well-known repertoires of asymmetric strategies that erode and deteriorate the stronger country’s position, without achieving domination.

Relations between the world’s major powers are indeed very important. But sustainable leadership relies also on constructive relationships with small countries. Wasting political, economic, and social capital on mismanaged and unnecessary conflicts not only alienates allies but also pushes neutral and potential non-aligned countries into the arms of rival great powers. Leadership, different from domination, is about attracting others to operate and think within one’s own agenda. That is the role of effective diplomacy.

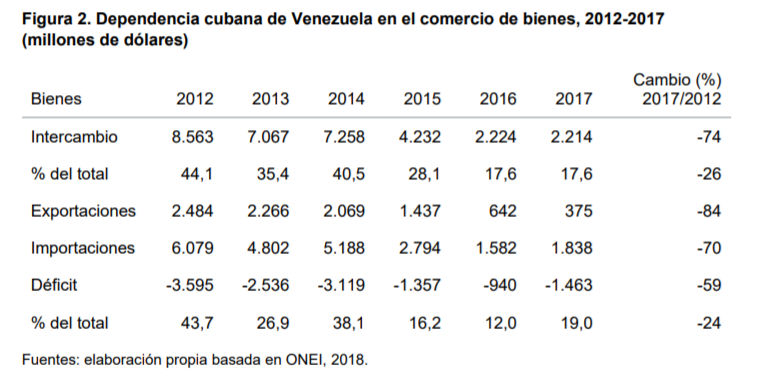

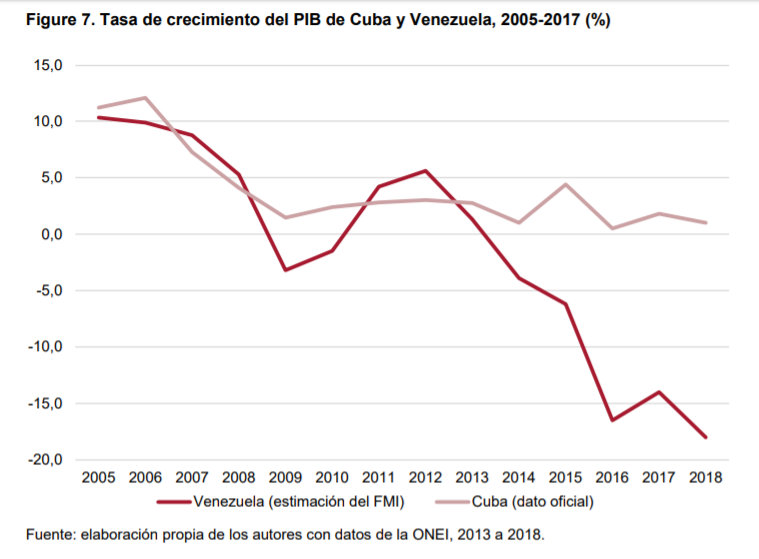

Trump’s return to sanctions will neither empower any relevant actor in Cuba’s politics nor change the Cuban government’s behavior. Cubans of almost every political persuasion will see Vice President Pence’s announcement that the United States will sanction oil shipments from Venezuela to Cuba as sanctions for the sake of sanctions—a means to create scarcity, desperation, and chaos in the island. Obviously, the Cuban people will suffer if Venezuela is forced to reduce the amount shipped daily to Cuba by some 20,000 to 50,000 barrels. But such sanctions will not peel off Cuba from the Bolivarian Alliance and would in fact encourage more security cooperation with Maduro and strengthen Havana’s alignment with Moscow and Beijing.

Trump’s new sanctions against Cuba replicate the same problems that the embargo has represented since the 1970s. First, the United States is alone geopolitically in its desire to double down on the Cuban embargo. Second, because the sanctions cater to domestic interests, Bolton’s speech repeated unrealistic expectations about imposing American diktat to third countries and provoking the fall of Maduro in Venezuela, Ortega in Nicaragua, and Díaz-Canel in Cuba. Third, limiting travel to the island and capping remittances will mainly harm Cuba’s emerging private sector, providing new incentives for mass migration to the United States. Cubans who are anticipating a sharp economic downturn are traveling to Mexico and Central America and headed north to the U.S. border.

The announcement of sanctions may spark catharsis in some segments of the Cuban and Venezuelan diasporas in South Florida, but history has proven that foreign policy for retribution therapy at the service of traumatized exile groups is not very effective.The announcement of sanctions may spark catharsis in some segments of the Cuban and Venezuelan diasporas in South Florida, but history has proven that foreign policy for retribution therapy at the service of traumatized exile groups is not very effective. A policy towards Cuba should be, well, a policy towards Cuba. For those passive opponents of communism within the Cuban government coalition, it is doubtful that these sanctions will create a wedge between development-oriented nationalists and control-oriented communists. In terms of those Cubans who openly oppose communism, the sanctions will not diminish their isolation from most Cubans, but will certainly increase their internal divisions over how to interact with the United States.

Consequences for Business and International Law

Reinforcing sanctions and threatening litigation over property claims will also make companies wary of doing business in Cuba. This could include the U.S. companies that began to explore business possibilities with Cuba at the end of the Obama administration, and farmers who sought an opening to a substantive market.

Mixing U.S. legitimate compensation claims on properties that were U.S.-owned at the time of nationalization with claims by Cuban citizens who lost their properties and became U.S. citizens later makes a difficult problem intractable. Cuba will never agree to pay for acts that were taken under its jurisdiction after 1959 between parties that were Cubans in Cuban territory. Even the Eisenhower government recognized the Cuban government’s prerogative to nationalize some properties that had been owned by corrupt members of the Batista regime.

When Congress first debated the Helms-Burton Bill in the late ‘90s, the U.S. State Department warned legislators that the sanctions would provoke clashes with other U.S. allies doing business in Cuba, for example in international institutions, such as the WTO. Under Helms-Burton regulations, the United States has sanctioned French, German, and Canadian companies for participating in commerce and investment transactions with Cuba that are plainly legal in their own countries and under international law. Economists and experts have warned repeatedly that the abuse of sanctions by the United States using the primacy of the dollar creates incentives for other actors to seek mechanisms to protect themselves from this financial vulnerability.

Indeed, after the announcement on the application of Chapters III and IV, European commissioners for Foreign Relations and Trade, Federica Mogherini and Cecilia Maelstrom, announced the EU’s intention to take the United States to the legal panel of the World Trade Organization (WTO). The EU and Canada also released a statement affirming that they “consider the extraterritorial application of unilateral Cuba-related measures contrary to international law. We are determined to work together to protect the interests of our companies in the context of the WTO and by banning the enforcement or recognition of foreign judgments based on Title III, both in the EU and Canada. Our respective laws allow any US claims to be followed by counter-claims in European and Canadian courts, so the US decision to allow suits against foreign companies can only lead to an unnecessary spiral of legal actions.”

Trump’s officials like Secretary of State Pompeo and National Security Advisor Bolton are indulging themselves in a 19th-century geopolitical time-warp, pontificating about the Monroe Doctrine while creating conflicts with Ottawa and Mexico City, and disregarding its allies’ positions on Cuba policy. Meanwhile, Russia and China are deploying a 21st century approach to Cuba and Latin America. Every area in which trade and investment in Cuba appears to be profitable is an open space for Russian and China’s technology and data-driven impulses.

Unleashing the illegal extraterritoriality of Helms-Burton law now will only add to the allies’ resentment of and skepticism against the U.S.’ capability to act as a leader beyond the short-term pressures of its domestic politics. It also provides ammunition to rival powers to denounce U.S. double standards. Why should Russia or China or Iran obey international law or UN resolutions if the United States so flagrantly violates them?

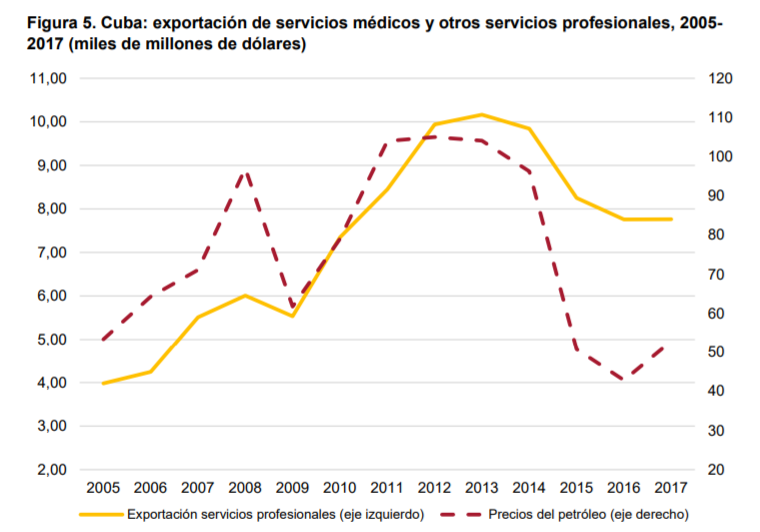

Plus, Trump’s sanctions will hamper also multilateral cooperation with Cuba such as the medical collaboration established by the Obama administration against the Ebola pandemics in West Africa in 2013 and 2014. An environment of hostility does not help foster any kind of constructive cooperation.

Non-Family Travel Ban

Finally, Bolton’s announcements in Miami included a ban on non-family travel to Cuba and a limit on family remittances, the amount of money sent by Cuban Americans to their relatives in the island. Limiting Cuban-American remittances is a prime example of double standards, where the United States dictate that the Cuban government curtails its involvement in the personal lives of citizens while trying to regulate how Cubans living in the United States spend the money they earn. U.S. taxpayers’ money will be spent on monitoring and persecuting people who only want to spend what belongs to them and travel to Cuba.

Trump’s prohibition of non-family travel to Cuba also privileges Cuban-Americans over other American citizens, including Cuban-descendant U.S. citizens, who fall into a second-class citizen category when it comes to travel rights. Cuban American legislators who cannot convince their constituencies to not travel to Cuba have pushed a compromise on the Trump administration that would bar other U.S. citizens from going to Cuba, while avoiding the backlash they will get in Miami if the government repeats former President Bush’s mistakes of limiting Cuban Americans’ travel to Cuba. More than 300,000 Cuban Americans travel to Cuba each year and will continue doing so.

It is ironic that average Cubans who live under a communist one-party regime, which Washington has deemed “a closed society,” have been allowed by their government to travel to the United States without limitation since October 2013, while U.S. citizens living under a liberal democracy are barred from traveling freely to Cuba. Most Cubans would like to change many dimensions of their country but not with a U.S. run transition but with their own timing, priorities, and sovereignty. The United States’ best contribution to Cuban democratization is to respect Cuba’s and other countries’ sovereignty and practice the freedoms it preaches.