FOREIGN POLICY at BROOKINGS

The full document can be found here:Richard E. Feinberg, Cuba’s New Economy and the International Response, Brookings, November 2011

“Reaching Out: Cuba’s New Economy and the International Response,” a new report by Brookings Nonresident Senior Fellow Richard Feinberg, urges the international development community to reach out to Cuba to promote its economic renewal. The report offers a detailed pathway for a gradual, systematic rapprochement between Cuba and the international financial institutions (International Monetary Fund, World Bank,

and Inter-American Development Bank). In the first such survey, it also provides an overview of the existing foreign assistance programs sponsored by capitalist nations in Cuba.

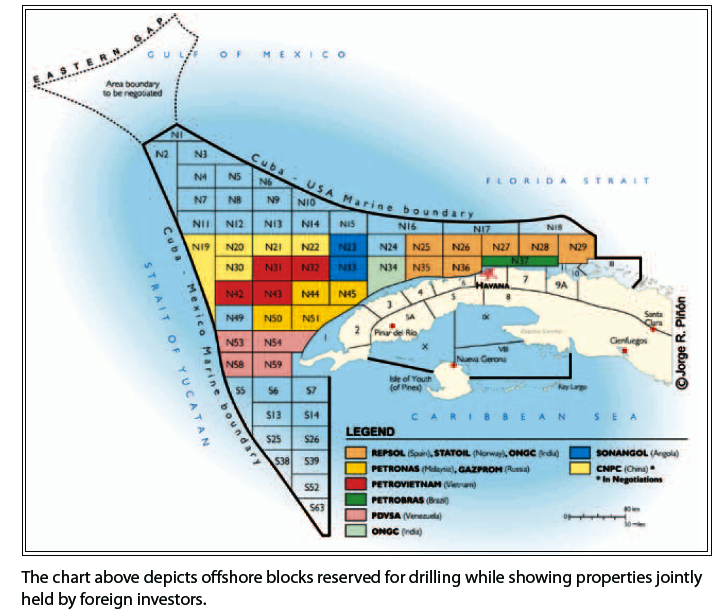

The study further analyzes the reform process occurring in Cuba today and describes Cuba’s strategy of engaging with the dynamic emerging market economies, largely

overlooked by U.S. analysts. The report finds that since the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Cuba has reached out to Europe and Canada, and most dramatically and successfully to the emerging market economies of China, Brazil, and Venezuela. Far from isolated by U.S. sanctions, the Cuban economy has become deeply integrated into global trading and investment markets.

Feinberg asserts that the international financial institutions (IFIs) house a wealth of accumulated knowledge and financial resources that fit well with the needs of a

reform-minded Cuba seeking greater economic efficiency and competitiveness. As

evident in their successful relations with Vietnam and Nicaragua, the IFIs –

having reformed their own terms of engagement – can perform effectively in

proud, strong states allergic to external interference. The study reviews the foreign assistance programs of donors such as the European Union, Spain, and Canada and concludes that development cooperation can achieve results in Cuba, improve the lives of beneficiaries, empower independent small producers, and promote decentralized decision-making to local communities.

Based on these research findings, Feinberg offers these specific policy recommendations:

· The international development community should support Cuba’s incipient economic reform process and bolster the struggling reformist factions within Cuba.

· The U.S. government should recognize that in Cuba today the opportunity is in economic reform, legitimized by the regime and openly debated by the Cuban public. Promoting economic reform is the most realistic option for advancing political pluralism in Cuba.

· The IFIs should complete their historical goal of full universality and bring Cuba in from the cold. The gradual warming of IFI-Cuba relations should begin with the provision of policy advice and technical training – prior to full membership.

· The US should not stand in the way of Cuba’s gradual re-admission to the IMF/World Bank. There is no better way to encourage progressive market-oriented reforms in Cuba.

According to Feinberg, the U.S. and international community can do more to help strengthen reform factions on the island. Feinberg concludes that inside Cuba, the forces of progressive change and the forces of bureaucratic inertia and resistance are locked in a fierce struggle. The United States should join with the international development community to bolster Cuba’s forces in favor of forward-looking economic reform.