By Ann Louise Bardach

Politico Magazine, June 10 2016

Original Article: BACKLASH IN CUBA

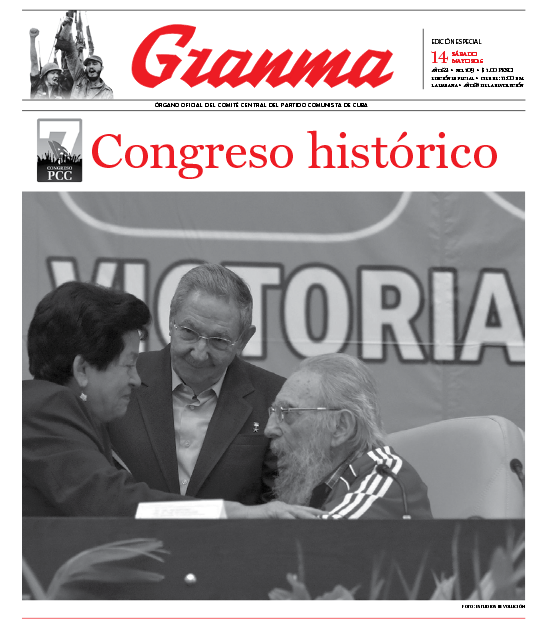

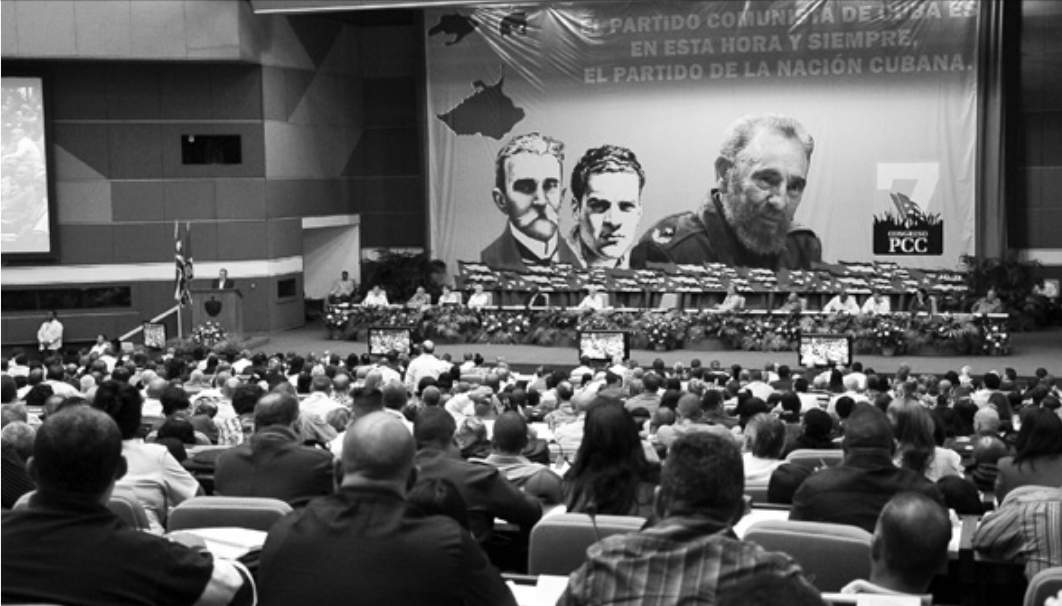

HAVANA—These days Fidel Castro doesn’t often leave his comfortable home in Siboney, a leafy suburb west of this city. But on April 19, the 89-year-old Cuban leader emerged, aides at his side, wearing a royal blue Adidas sports jacket over a blue plaid shirt, and was driven two miles to the immense Palacio de Convenciones. Inside he was greeted by a thousand members of the Communist Party, the ruling body that has been Cuba’s sole political party for half a century. They were wrapping up their four-day conference, generally held twice a decade.

Fidel is ailing and officially retired, having incrementally handed the reins of power to his brother Raul over the past decade. But he remains a history buff, a news junkie, and a man keenly concerned with his legacy. And he was not pleased with what he had been hearing.

President Barack Obama had spent three high-profile days in Havana at the invitation of Raul. And the visit, to Fidel’s dismay, had been an immense public success, generating as much excitement and buzz on the island as the arrival of The Rolling Stones for a free concert a few days later. While state media treated Obama with cautious distance, there was no mistaking the thrill of ordinary Cubans as the president toured local sights, watched a baseball game, and drove through Havana with his family and entourage. They dubbed the president Santo Obama. “He’s more popular than the Pope!” one exultant habanera told me.

President Barack Obama had spent three high-profile days in Havana at the invitation of Raul. And the visit, to Fidel’s dismay, had been an immense public success, generating as much excitement and buzz on the island as the arrival of The Rolling Stones for a free concert a few days later. While state media treated Obama with cautious distance, there was no mistaking the thrill of ordinary Cubans as the president toured local sights, watched a baseball game, and drove through Havana with his family and entourage. They dubbed the president Santo Obama. “He’s more popular than the Pope!” one exultant habanera told me.

If the first state visit by a sitting president in 90 years struck Fidel as an unseemly and undeserved victory lap, there was troubling news as well from the Southern Hemisphere as well. Two of the island’s staunchest allies were fighting for their political lives. Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff was nearing impeachment; Argentina’s former president, Cristina Kirchner, was about to be indicted. Indeed, the entire left-wing coalition of Latin America, methodically cultivated by Fidel for decades, was unraveling. The death of Cuba’s Midas-like patron, Hugo Chavez of Venezuela, had birthed a feeble successor who is unlikely to survive the next year; Ecuador’s leftist president was bowing out, while Castro champion Evo Morales of Bolivia had lost a referendum for another presidential term. Peru and Uruguay had lost their center-left leaders. If not a political tidal wave, a domino effect of sorts was shifting the Southern Hemisphere from left to right.

Fidel Castro, Cuba’s Maximum Leader, understood that something had to be done.

Cuba’s Party Congress sets the economic and political agenda of the island, and many, on and off the island, had anticipated that this year’s conclave would further crack the door open to more reform. As the U.S. and Cuba have navigated their rapprochement, their progress has continuously been buffeted by the alternating agendas of the two brothers: Fidel, the intransigent revolutionary, and Raul, the cautious reformer. Obama hoped that a state visit before the Congress would give a boost to Raul’s reform-minded approach, however modest.

Cubans, too, had their eye on the meeting, and many of them expected that the Party would at least start to retire its octo- and nonagenarian ruling elite, the historicos who came up with Fidel and Raul and have been governing the island since. Raul himself had fueled those hopes by urging an age limit of 70 for senior Party officials.

It did not happen that way. Instead the Party’s elders, with the blessing of Fidel, spent the first three days of the Congress issuing a series of retrograde edicts and re-establishing their hegemony. Rejecting the retirements of the old guard, they went on to quash reforms intended to rescue the country’s moribund economy.

For a finale, Fidel addressed the Congress for the first time since 1997. The date of his appearance, April 19, was not coincidental. It fell on the 55th anniversary of the doomed U.S.-sponsored Bay of Pigs invasion, when Fidel’s army vanquished the CIA’s ill-conceived coup, captured thousands of U.S.-backed rebels, and utterly humiliated the world’s greatest superpower.

The days when Fidel routinely gave furious six-hour orations in olive-drab military garb are long gone. Now with hair white as the sands of Varadero Beach, he did not attempt to stand on his feet. Instead, he was helped to a chair at the center of the dais. “This may be one of the last times I speak in this room,” Fidel somberly told the throng.

Although Fidel spoke with a gravelly rasp, those looking to hear conciliatory words were quickly disabused of that hope. “The ideas of Cuban Communists will remain as proof on this planet,” he insisted, and their achievements “will endure.” And to that end, the firebrand Fidel exhorted those present —charged with setting Cuba’s agenda through 2030—“to fight without truce.”

“Soon, I’ll be 90 years old. Soon I’ll be like all the others,” Castro intoned as if giving his own eulogy. “The time will come for all of us.”

Then the old lion, albeit with a patchy beard and a thinning mane, roared again, one last time: “We must tell our brothers in Latin America—and the world,” he declaimed, “that the Cuban people will be victorious!”

In the closed, hermetic world of Cuban politics, Fidel’s speech marked a pivot in what has arguably been the country’s most remarkable three months since the Missile Crisis of 1962. The ceaseless whiplash includes a ballyhooed U.S. presidential visit, a Party Congress slamming the door on reform, a Fidel valedictory finale, and a series of fresh dramas in the long-running saga of the Brothers Castro.

On June 3, Raul turned 85, to be followed by Fidel’s 90th birthday on August 13, a pair of personal milestones that have the brothers keen to cement their legacies. “The Castros are robust and long-lived,” boasted Raul on his big day; he also chatted with Russia’s Vladimir Putin, who called offering birthday wishes.

As the brinkmanship between the two Castros plays out, it’s likely to shape the course of U.S.-Cuban relations for the next generation. In that respect, it was possible to see the Congress as an episode in the long-running drama between two brothers to whom appearances matter deeply. Raul, the internationalist, got to produce the Obama Show. Fidel, the nationalist, won the right to orchestrate the Party Congress and to deliver his response to President Obama’s proposal of accelerated reform and cooperation with the U.S.

And Fidel’s message was unmistakable: Over my dead body.

This was hardly the step forward the White House had hoped for when it orchestrated its historic, if hastily planned, state visit in March. For Obama, Cuba was his “Nixon in China” moment, a legacy move to close the last chapter of the Cold War in our hemisphere.

It could not have contrasted more clearly with the previous U.S. presidential visit. In 1928, the Republican Calvin Coolidge sailed into Havana Harbor on a battleship. Obama, on the other hand, delivered his first words to the Cuban people before he even debarked from Air Force One. They came, cool, breezy and direct, in the form of a tweet. “¿Que bolá Cuba?” he tweeted, using the island slang for “what’s happening?” “Just touched down here, looking forward to meeting and hearing directly from the Cuban people.”

Cuban officialdom adopted a noticeably stiffer tone. Despite Obama being the single most important head of state to visit since 1959, Raul Castro—who has personally greeted more than one pope and innumerable national leaders upon their arrival—did not appear at the airport to welcome him. Instead, when the First Family touched down amid an insistent gray rain, they were met by Foreign Minister Bruno Rodriguez, who greeted the president on the tarmac with a cordial handshake.

The government-run media gave a similarly cool treatment. On the eve of Obama’s visit, Granma, the organ of the Communist Party, devoted its six thin pages to the arrival two days earlier of President Nicolás Maduro of Venezuela, Cuba’s principal patron since the collapse of the Soviet Union. In Havana, Maduro was robustly feted, even bestowed a new honorific title, with Raul declaiming that “we will never abandon our Bolivarian revolutionary friends.”

Obama’s trip had been something of a rush job, as state visits go, and behind the scenes, the U.S. had been on the back foot from early in the process. The date of the trip hadn’t been finalized until January. One consideration in the timing was to ensure the visit came prior to the Party Congress, with the White House hoping to be a moderating influence when it convened. But the driving force, according to sources at both State and the Vice President’s office, was that the president and first lady very much wanted a family trip, and the March 20-23 dates coincided with spring break at Sidwell Friends School for daughters Malia, who’s been studying Spanish, and Sasha.

The trip planning also augmented tensions between the White House and the State Department that dated back to the historic Cuban deal announced in December 2014. The landmark agreement had effectively ended the Cold War between the countries and began the process of normalization: Cuba agreed to release numerous political prisoners and return imprisoned USAID contractor Alan Gross along with a significant U.S. intelligence asset, Rolando Sarraff, in exchange for the U.S. returning the remaining three of the “Cuban Five” convicted spies. Although negotiations like this would normally be led by the State Department, Obama had deputized his trusted aide and speechwriter, Ben Rhodes, to make a deal with Cuba happen. The 18 months of secret negotiations largely bypassed the State Department; only one State veteran, Cuba policy specialist Ricardo Zuniga, who partnered with Rhodes, was fully trusted by Obama’s innermost circle, to maintain the secrecy demanded by the administration. Likewise, Cuba’s Foreign Ministry, known as MINREX, was exiled from negotiations. The key player on the Cuban side was none other than Colonel Alejandro Castro Espín, Raul’s 50-year-old son, a steely hard-liner widely believed to be his father’s heir apparent.

The rushed trip also gave the Cubans leverage to shape the agenda, or try to: No meetings with human rights activists, they insisted, and they would decide the guest list, including which U.S. reporters made the cut—a loaded issue with Cuba, which has a long history of barring American reporters who report seriously on the island.

Matters were not looking good, and the press around the reconciliation was getting worse, until Secretary of State John Kerry canceled a trip to Havana in protest weeks before the state visit. Kerry’s bluff worked, and from then on, the U.S. got what it wanted. The Cubans reluctantly issued visas for the reporters; the president had meetings with entrepreneurs, dissidents, human rights activists and even held a news conference, all to be recorded by live television coverage.

***

It is nearly impossible to overstate the impact of President Obama’s arrival in Cuba. The shift in outlook was tectonic. In the course of the visit, I heard more than one habanero refer to Obama as “El Negro de Oro”—the Golden Black Man, a flattering pun on “black gold.” It didn’t hurt that to many Cubans, Obama just looks Cuban; his mixed-race background gives him something in common with the half the island’s population that identifies as mulato, black or mestizo today.

The Obama family made the requisite tourist stops, including the city’s grand Cathedral, built in 1777 from blocks of coral; they took a walking tour led by Havana’s remarkable official historian, Eusebio Leal. Despite failing health and being in considerable pain, Leal gamely guided the Obamas through historic Havana in and around the Plaza de Armas.

The buzz of la bola en la calle—Cuban street gossip—was that the visit had prompted previously unimaginable upgrades to parts of the capital. Every building that the Obama entourage passed had been repainted, and every road his limousine traversed had been repaved. Some streets were still being paved and re-striped just hours before his arrival. “Come visit us,” cried out residents of neglected, pot-holed barrios in what became a weeklong running joke, “y llevar el asfalto!” — “and bring the asphalt!”

The culmination of the trip was Obama’s exquisitely crafted speech, delivered in downtown Havana’s Gran Teatro with Raul Castro and the senior Politburo present, along with an array of invitation-only favored Cubans. “I have come here to bury the last remnant of the Cold War in the Americas,” Obama began, thus ending the half century David-and-Goliath face-off that once almost brought the world to its end. The speech, written by Rhodes, hit every note. Millions of Cubans watched, many saying later they were overwhelmed by emotion, as an American president spoke directly to them, not at them.

“I had tears in my eyes,” said Marta Vitorte, who watched the speech in her Vedado apartment. A former official in the Foreign Ministry, Vitorte for the past decade has run one of Havana’s most popular and upscale casa particulars, or private home rentals. “This is the beginning of the future of Cuba,” she gushed.

But for the island’s 11-million-plus inhabitants, an even more jaw-dropping moment had come earlier in the visit. On Day Two, Obama had cajoled Raul into participating in a live news conference, taking unscreened questions from American reporters.

Considering Cuba’s antagonism towards a free press, Raul’s participation was stunning and, no doubt, a spontaneous decision he quickly regretted. The Cuban leader was plainly displeased by a question on human rights by NBC’s Andrea Mitchell, but he was infuriated by CNN’s Jim Acosta who asked, “Why are there Cuban political prisoners in your country?” Raul visibly bristled, having never endured an unfriendly press query. “Give me the list right now of political prisoners to let go of them,” Raul huffed. “Tell me the name or the names … And if there are political prisoners then before night falls, they will be free. There!” (Lists of prisoner names were promptly circulated on social media—none of whom are known to have been released since.)

“Oh my god,” said a former Cuban diplomat. “It made Raul look weak. No one here has ever seen anything like that.” | AP Photo

As the conference streamed live, Cubans watched a flustered Raul lose his cool, then abruptly end the news conference and march over to Obama to raise his arm in a victory salute. A bemused Obama was having none of it, and let his arm dangle. “Oh my god,” said a former Cuban diplomat. “It made Raul look weak. No one here has ever seen anything like that.”

***

Obama’s show-stopping appearances could only have mortified Fidel Castro, a public-relations genius, who was keenly monitoring the visit from his home. “Never abandon propaganda—even for a minute,” he had counseled compatriots in a 1954 letter. “It is the very soul of our struggle.”

Today, for hard-liners of Fidel’s generation, la lucha, the struggle, means just two things: keeping the principles of the Revolution alive in Cuba; and keeping themselves alive and in power.

At the very minimum, Obama had rewritten Fidel’s carefully scripted drama, in which the U.S. plays the rapacious foe. Suddenly, America seemed far less menacing. As the Cuban novelist Wendy Guerra wrote, in the wake of Obama’s visit: “Since you left, we are little more alone, because now we have to find another enemy.”

“The enemy always drove the story,” says Marilu Menendez, a Cuban exile and branding expert who now lives in New York. “It justified all of [Fidel’s] excesses.”

Even before Obama left the island, Fidel let it be known that that he took a dim view of the visit. Just days after Air Force One departed, an article appeared in the state-run Tribuna de la Habana that accused Obama of lording over a racist country and “inciting rebellion” in Cuba by meeting with pro-democracy activists. Its headline, roughly translated, “Black Man, Are You Dumb?” was a firebomb. “Obama came, saw, but unfortunately, with the pretend gesture of lending a hand, tried to conquer,” wrote Elias Argudín, a government loyalist, “choos[ing] to criticize and subtly suggest … incitements to rebellion and disorder, without caring that he was on foreign ground. Without a doubt, Obama overplayed his hand. Minimally, I can say is … ‘black man, are you dumb?’”

Following a wave of blowback, Argudín offered a quasi-apology for “causing offense,” noting that he himself was black. In a typically mysterious Cuban chess maneuver, the story was briefly deleted, then reposted on the paper’s website, while running in the print edition.

The column was only the first public salvo from hard-liners signaling their distress over the American president’s visit. A few days later, Fidel himself published a searing 1,500-word public letter, a full-throated denunciation of the visit and, by implication, Raul, who had hosted it. Entitled “Brother Obama,” it ran on Page 1 of Granma. Obama’s grand speech (which had begun with a famous line from the beatified patriot José Martí) was derided by Fidel as “honey-coated”—merely by listening to it, he warned, Cubans “ran the risk of having a heart attack.” And then Fidel dropped the hammer: “We don’t need El Imperio—The Empire—to give us any presents!”

Though Fidel and Raul’s lives have been anchored in decades of sibling love, collaboration and feuding, Fidel must have known, or quickly learned, that his public harpooning had gone just a bit too far. And so on April 8, a week before the highly anticipated Congress, Fidel made another unusual outing from his home. Wearing a white blousy sports jacket with a black wool scarf tied around his neck, Castro, aided by a cane, spoke briefly at the school named for his late sister-in-law, Vilma Espín.

Espín had been Raul’s wife and compañera in the Revolution from the early 1950s, and had served as Cuba’s de facto first lady. But when she died in 2007, Fidel did not attend her funeral. His own illness served as a reasonable excuse, but as one former Cuban official told me in Havana, none of Fidel’s family—neither his children nor his wife, Dalia—attended either. The snub deeply disappointed the family-centric Raul, who also serves as the Castro clan’s patriarch. Since then, the official said, Raul typically has a weekly family dinner, not with Fidel’s brood, but with his in-laws, the Espíns.

So it was impossible not to interpret Fidel’s tribute as a peace offering to Raul, in advance of the Congress, where it was imperative that the brothers present a unified front. “I’m sure that on a day like today, Vilma would be happy,” Fidel intoned to the schoolchildren in his weakened voice.

Vicki Huddleston, former chief of the U.S. Interests Section in Havana, said the brothers knew they needed to project unity. “They do not want it to appear that there are divisions,” she said. Veteran Cuba negotiator and U.S. ambassador to Mexico, Roberta Jacobson, suggested that the brothers’ brinkmanship was sometimes simply ritual role-playing—a kind of “good cop-bad cop within the Castro family.”

***

The dynamic between the Brothers Castro is of great import to Cubans, of course, and also determines what issues they allow on the table with American negotiators, and at what pace they are willing to address them.

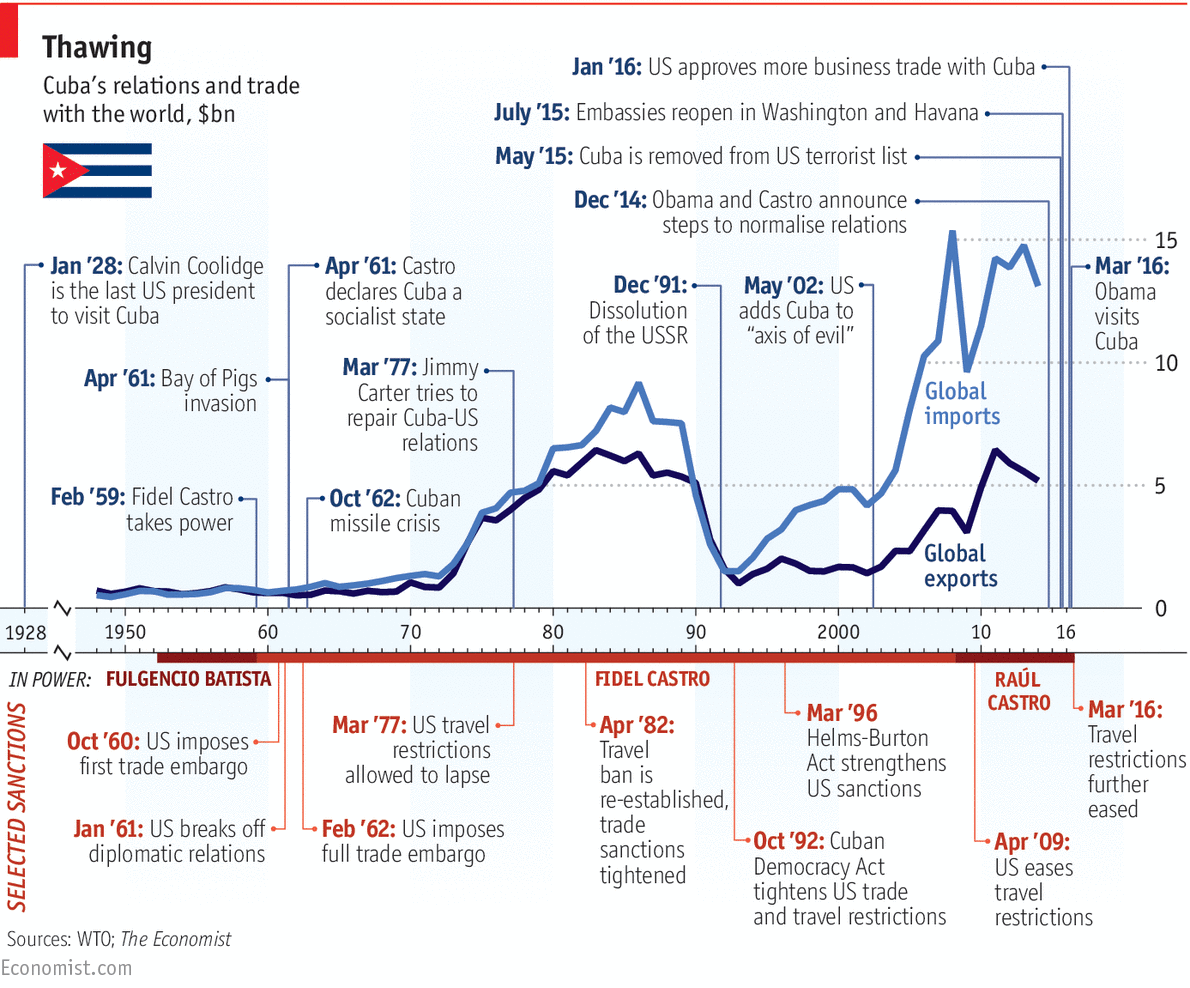

On many issues the brothers are genuinely in lockstep, such as ending the U.S. embargo. While Cuba relentlessly hammers on about “el bloqueo”—the blockade, the hyperbolic term it uses for the embargo—its current prohibitions have been whittled down to a fraction of what they once were. Through executive actions, the Obama administration has lifted an array of trade and investment restrictions. Completely normalized trade and banking will have to wait for Congress to rescind the embargo officially, but whether Hillary Clinton or Donald Trump wins, the Cubans think they will have the requisite votes in Congress to get it done. With GOP Senators Jeff Flake and Rand Paul leading the charge, they expect a vote to come at some point in 2017. But until then, the embargo continues to be useful propaganda about the bully “Empire” to the north.

The embargo can be seen as Cuba’s short game. The longer game is Guantánamo—the territory, not the prison. Even more than the embargo, this 45 square miles of Cuba’s easternmost province has long served as Exhibit A of the crushing foot of El Imperio. As Raul reminded Obama on Day Two of his visit: “It will also be necessary to return the territory illegally occupied by Guantánamo Naval Base.”

While the prisoners held in Gitmo are the issue attracting global attention, for Cuba, they’re simply helpful propaganda in its quest to get its land back. America does have a lease, a 1903 deal stipulating that Guantánamo and its deep-water harbors be used as a “coaling station.” (The rent is $4,085 annually, and the Castros proudly boast that they never cashed a rent check—although they did cash one in 1959.) Cuba now argues that America’s current use of the land is in violation of its lease. “If this was a straight-up landlord-tenant law, the landlord would kick your butt right out,” says Jose Pertierra, a Cuban-born lawyer who shuttles between Havana and Washington.

A former Cuban diplomat told me he expects the Gitmo crusade to get louder and more insistent going forward. “We don’t really care about the prison,” he said, “but [the government] is going to politicize it as a human-rights violation [and] a breach of the lease.” In Havana, I asked Ben Rhodes if the Cubans had put Gitmo on the table as a chip. “There are never discussions in which Guantánamo does not come up,” he answered.

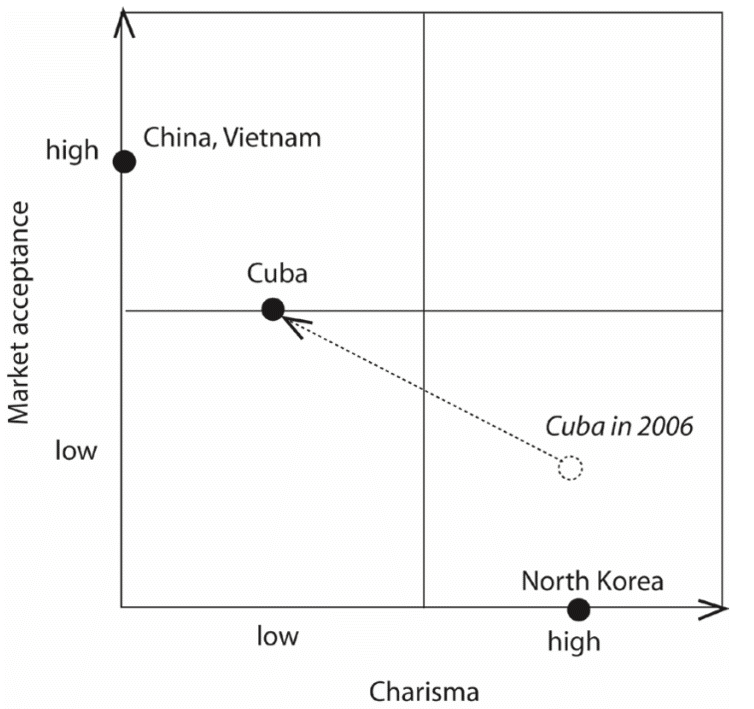

As talks between the countries haltingly advance, it is on domestic economic and political issues where the internal Cuban factions part company. In the 1990s, with the collapse of their Soviet patron, Raul began to see Cuba’s future very differently than his older brother. Raul had studied and visited China and Vietnam, and he liked what he saw: economic powerhouses fueled by competitive capitalism but all under the steely control of the Communist Party.

Fidel, on the other hand, mistrusted any version of capitalism, however dressed up as socialist entrepreneurism. He had railed against perestroika and glasnost and repeatedly warned Mikhail Gorbachev it would be the beginning of the end. (And indeed, it was the end of the Soviets’ billion-dollar patronage of Cuba.)

Unlike his brother, Raul has acknowledged cracks in the pillars of Cuba’s 65-year-old political system; insiders consider them serious. “There is no more discipline within the traditional ranks,” a retired government official told me. “No one wants to belong to the CDR [Committees for the Defense of the Revolution, the neighborhood snitch organs]. No one feels they have to belong to the Communist Party.” He added: “Five years ago, if you didn’t belong to the CDR or the Party, you weren’t going to get a promotion or could get in trouble. But there is no more fear about it.”

Likewise, such bastions of the Revolution as the Federation of Women, the Workers Union, and the Young Communists League are losing members, I was told. All these organs that have buttressed the Revolution are in decline, losing momentum as membership oozes away. “Everybody’s looking down the road about how to be an entrepreneur or a capitalist,” said a man who has turned his home into a casa particular.

For the past two years, Raul has been beseeching allies and trading partners—Russia and much of Europe—to forgive loans and debts incurred over decades, an estimated $51.5 billion, according to Emilio Morales of the Havana Consulting Group. (That figure that doesn’t even include debts owed to Venezuela and Brazil.)

And there is a relatively new reality on the island: corruption. “It’s a daily event,” he said. “If you have money, there’s nothing you cannot get,” then lowering his voice, “even a visa to leave Cuba.“

While Fidel may choose to turn a blind eye to the domestic woes of his country, he is keenly attuned to the fact that there are larger, inexorable forces at work. The Southern Hemisphere is plainly drifting away from Cuba. In 2006, as he lay gravely ill, Fidel could gaze out at Latin America—populated by Lula in Brazil, Evo in Bolivia, the Kirschners in Argentina and his adoring student and patron, Hugo Chavez—and rest serene that fidelismo and Cuba’s future were secure. If Fidel had died that year, as he has said he very nearly did, he would have been one satisfied soul.

But 10 years later, he has lived to confront a radically different picture. Cuba has lost all its patrons, except for the dramatically reduced oil shipments from Venezuela. Both Russia and China have set limits on their future largesse. Meanwhile, the U.S. rapprochement is making it inescapably clear that Cuba’s economic salvation lies, once again, as it did in the first half of the 20th century, in American investment and tourism—meaning ever-deepening ties to Fidel’s lifelong bête noire, the U.S.

So despite the rhetorical saber-rattling, and the alternating star turns of Raul and Fidel, Cuba is going through the only door that, for now, is open: Making friends with Uncle Sam. With no fanfare or pronouncements, U.S. and Cuban negotiators met recently and laid out an agenda for meetings well into the next year covering property claims, trade, environmental concerns and cooperation on narcotics.

In late May, the Cuban government announced that small and medium-size businesses would be legalized. The Party Congress may have repudiated change, but change is happening nonetheless.

Most crucially, there is the daily bonanza of ever-multiplying dollars from U.S. tourism. “More than 94,000 Americans have visited Cuba from Jan-Apr 2016,” proudly tweeted Josefina Vidal, a Cuban official who heads the U.S. division of the Foreign Ministry in May, “a 93% increase with respect to same period 2015.”

Leonardo Padura, Cuba’s most famous living writer, recently tried to explain his country’s contradictions. “If you say [Cuba] is a communist hell or a socialist paradise, you’re missing all the nuances,” he told EFE, the Spanish news agency. “Cuba is a society that apparently has not changed, but it really has.”

That assessment could apply just as well to Raul. Both a “reformer” and a “historico” by definition and personal loyalty—having fought alongside Fidel since 1952 and, since 1959, having run the Cuban Army, the country’s most powerful political organ—Raul has evolved into a pragmatist of necessity over the past 25 years. At the same time, Fidel has doubled down his resolve to resist reform. And like Cuba, the relationship between the deeply bonded brothers apparently has not changed, but it really has.

At his birthday last week, when Raul was toasted by family and friends after hosting a Caribbean summit, there was much to celebrate—replete with historical ironies. Fidel may have rescued Cuba from the clutches of the U.S., but it is Raul who is rescuing Cuba from Fidel.

Ann Louise Bardach is the author of Cuba Confidential (2002) and Without Fidel: A Death Foretold in Miami, Havana and Washington (2009), as well as the editor of The Prison Letters of Fidel Castro and Cuba: A Travelers Literary Companion. She interviewed Fidel Castro in 1993 and 1994 and met Raúl Castro in 1994.