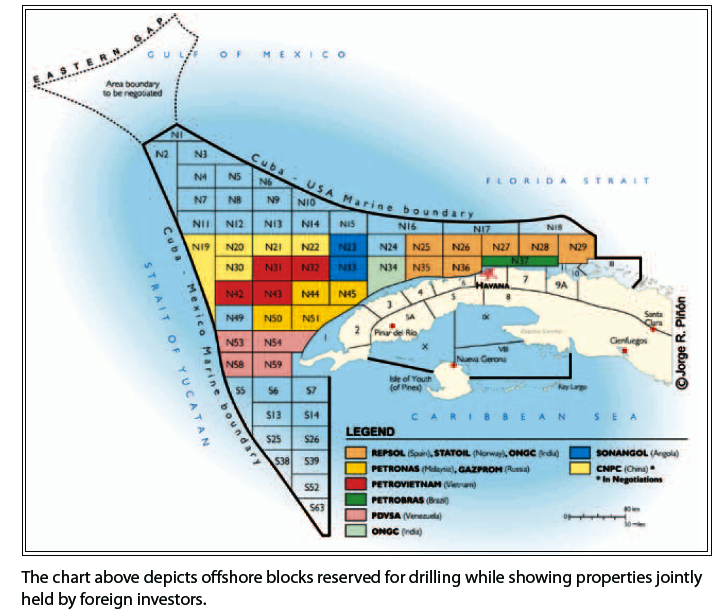

John Daly,Oil Price; Tuesday, 27 September 20, Courtesy of Jorge R. Piñón.

[Oil Price is a well respected oil price research and analysis publication]

For 51 years the U.S. has imposed an economic embargo against Cuba, severely crippling the island’s economy for its effrontery in choosing a socialist path for development, a policy confirmed and intensified in the wake of the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis.

Now the unlikeliest of economic interests may be bringing the two countries closer together – oil.

Specifically, oil deposits in the Florida Straits between Key West and Cuba.

Spain’s largest oil company, Repsol-YPF, has contracted the massive Italian-made Scarabeo 9 semi-submersible oil rig, currently en route from Singapore, to arrive in the Florida Straits by the end of the year after the end of hurricane season to begin exploring Cuba’s offshore reserves. Repsol-YPF, which drilled Cuba’s first onshore well in 2004, intends initially to drill six wells with the Scarabeo 9 rig.

Cuba, which currently produces a paltry roughly 50,000 barrels of oil per day from onshore sources, is understandably keen to begin exploiting its offshore reserves, which estimates place between 5-20 billion barrels of crude in a 43,000 square-mile drilling area containing 59 maritime fields it has designated off its northern coast. While Fidel Castro’s close ally, Venezuelan Hugo Chávez currently dispatches 120,000 bpd to Cuba on very favorable financing terms, the arrangement is heavily dependent on the friendship between octogenarian Castro and cancer-stricken Chávez, hardly a recipe for permanency.

While Repsol-YPF is the first out of the gate, other concessionaires include Norway’s Statoil ASA, India’s state-owned Oil and Natural Gas Corporation Ltd (ONGC) and Brazilian state oil company Petroleo Brasileiro, or Petrobras.

Note the total absence of U.S. oil companies – that’ll punish those pesky Commies!

While the 1982 United Nations Convention of the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) maritime treaty provides littoral nations with a 200-mile Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) extending 200 miles offshore for exploiting maritime reserves, in 1977 U.S. President Jimmy Carter signed a treaty with Cuba that essentially split interstate waters and created for Cuba an “exclusive economic zone” extending from the western tip of Cuba northward to roughly 50 miles from Key West, which Havana then divided into 59 parcels for leasing.

So, what is Washington’s view of the latest developments? Depends how close you get to Florida, where politicians rely on the anti-Castro Cuban émigré vote to stay in power.

Congressional leaders like Cuban-born Republican House of Represenatives member Ileana Ros-Lehtinen and U.S. Senator Florida Democrat Bill Nelson would like to see Cuba scrap its offshore drilling plans altogether, a most unlikely scenario.

A more realistic approach is embodied in last week’s visit to Cuba by International Association of Drilling Contractors chief executive Lee Hunt, who as part of a joint Environmental Defense Fund traveled to the island with William Reilly, a former Environmental Protection Agency administrator and co-chair of the White House task force investigating the 2010 BP oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico, Royal Dutch Shell former vice president of deepwater drilling Richard Sears and Environmental Defense senior attorney Fund Dan Whittle to discuss plans to deal with possible oil spills from the Cuban projects, and whether U.S. firms might participate in cleanup activities.

The 64,000 peso question is whether Washington will allow such participation. Despite the embargo the Obama administration has said it will let U.S. companies do business with Cuba’s foreign partners in that context on a case-by-case basis. The reality of a Cuban oil spill having effects on U.S. waters has even allowed a bit of reality to intrude on Ros-Lehtinen’s policies, as she recently observed that “should a disaster occur and Florida’s waters be threatened, U.S. regulations could allow U.S. oil spill mitigation companies to engage in clean-up activities.”

Another potential factor in influencing Washington’s decisions is that Repsol-YPF may not be going it alone, either. Mexican daily La Jornada reported earlier this month that Mexican state oil company Petroleos Mexicanos, more familiarly known as Pemex, is shifting from its former “Mexico first” policy and intends to begin foreign operations, including offshore drilling in Cuba. The development is hardly surprising in light of Pemex’s recent announcement that it spent $1.6 billion to raise its stake in Repsol YPF from 4.8 percent to 9.8 percent, with the idea of creating a strategic partnership. In raising its stake, Pemex said it will unite its votes on the Repsol board of directors with those of Spanish construction company Sacyr Vallehermoso, which owns 20 percent of Repsol’s shares. Pemex seems to be emulating the successful global strategy of Brazil’s Petrobras.

As Pemex, ONGC and Petrobras are all state-owned companies, while the Norwegian government owns a majority share in Statoil ASA, to interfere with these companies’ activities is to roil relations with their parent governments, and in the case of Pemex, such a stiff-necked policy could have ominous implications for U.S. energy security, as according to the U.S. Energy Administration, the United States total crude oil imports now average 9,033 thousand barrels per day (tbpd), with Mexico being the second largest source of U.S. imports, running at 1,319 tbpd.

It may be time for a rethink of U.S. policy towards Cuba. After all, Castro has outlasted the Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson, Nixon, Ford, Carter, Reagan, Bush I, Clinton and Bush II administrations, so it rather seems unlikely that the embargo has produced the desired effect of removing the Cuban government.

And oil spills know no nationality.

OilWells, just off the Via Blanca, the road from Havana to Matanzas, 1999

OilWells, just off the Via Blanca, the road from Havana to Matanzas, 1999