Six months after demonstrations, courts have quietly started imposing harsh charges such as sedition

Ed Augustin in Havana

The Guardian, Last modified on Sat 15 Jan 2022 10.02 GMT

Original Article: Cuban Protesters Sentenced

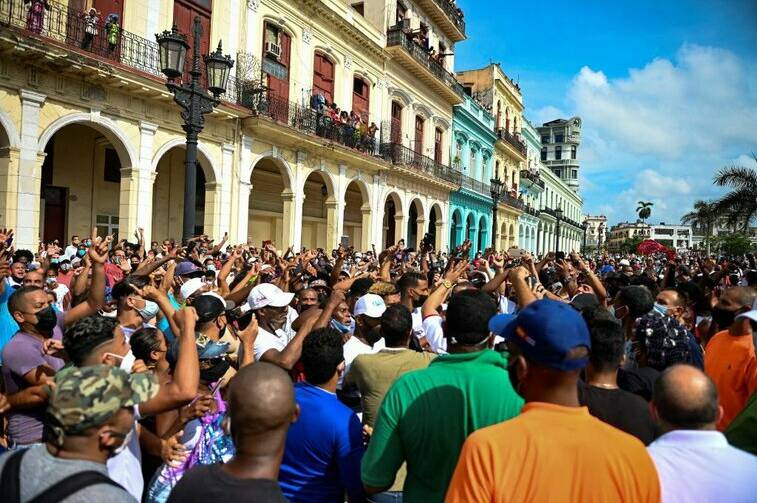

One Sunday last summer, 18-year-old Eloy Cardoso left his mother’s house on the outskirts of Havana to collect an Atari game console from a friend. He’d stayed at home the previous day, while the largest anti-government demonstrations since the revolution had ripped through Cuba.

The authorities had managed to quell the protests in most of the country overnight, but not in La Güinera: unrest was still raging in the humble and normally calm neighbourhood, and Eloy walked out into a bloody brawl. Shops were smashed and looted, party supporters wielded clubs, police wrestled with youths, and one man was shot dead. Amid the tumult, Cardoso began to throw stones at the police.

He was arrested a few days later, and at a closed trial earlier this week he was sentenced to seven years in prison. The trial is one of scores currently playing out across the island, as, six months after the demonstrations, Cuban courts have quietly started imposing draconian sentences on the protesters who – sometimes peacefully, sometimes less so – flooded the streets last summer.

Though the state has a history of issuing stiff sentences to organised political dissidents, the punishments now being meted out are unusually severe.

“They want to make an example of him,” said Cardoso’s mother, Servillia Pedroso, 35, holding back tears. Eloy Cardoso’s mother, Servillia Pedroso, left, and Migdalia Gutiérrez, whose son, Brunelvil, has been sentenced to 15 years.

Because her son is at college, police initially told her he would get a “second chance” charging him with “public disorder” and telling him he would get away with a fine. But in October, the charge was upgraded to sedition: in other words, inciting others to rebel against state authority.

Since December, more 50 people in La Güinera have been sentenced for sedition, according to the civil society organisation Justicia 11J. Most are poor, young males. Justicia 11J said more than 700 people were still being detained following July’s protests, with 158 of those accused of or already sentenced for sedition. Last week one man in the eastern province of Holguín was sentenced to 30 years.

Erika Guevara-Rosas, Americas director at Amnesty International, said detainees have faced summary proceedings without guarantees of due process or a fair trial. “Prosecutors have pushed for disproportionately long sentences against people who were arrested in the protests. In addition, many people stand accused of vague crimes that are inconsistent with international standards, such as ‘contempt’ which has been consistently used in Cuba to punish those who criticise the government,” she said.

“The state is trying to send the message that there are dire consequences to rebelling against the government,” said William LeoGrande, professor of government at American University in Washington. “The fact that the government feels under and is under unprecedented threat – not just from increased US sanctions but from the pandemic and the global economic situation – makes it less willing to tolerate any type of dissidence.”

Trump-era sanctions contributed to the food and medicine shortages people were protesting against. The sanctions also slowed vaccine production, aggravating a Covid surge that was sweeping through the island at the time, and contributing to the fury. But many protesters also wanted freedom from Communist rule.

Economic complaints are a constant in La Güinera: it’s hard to afford shoes and medicine. A schoolbag costs 2,500 pesos – more than half a teacher’s monthly salary.

“I’m sure that if it wasn’t for the economy, none of this would have happened – but the economy never improves,” said Yusniel Hernández, 36, a teacher turned taxi driver, who said a dozen friends had been incarcerated for throwing stones and assaulting police officers.

Analysts say the government is using exemplary sentencing to snuff out any further protests because it is bracing for further economic hardship. As sanctions have hardened, a longstanding siege mentality among the leadership seems to have ossified in recent years. The fact that the Biden administration reversed its policy of normalisation with the island after July may be another contributing factor.

But the pain from the crackdown is palpable. “None of these kids were activists, they don’t belong to any organisation,” said Migdalia Gutiérrez, 44, whose son, Brunelvil, 33, has been sentenced to 15 years. If someone has nothing to do with politics, and you are accusing them of political stuff, then you are making them political prisoners,” she added.

Her nextdoor neighbour, María Luisa Fleitas Bravo, 58, lives in poverty. The roof of her kitchen, living room and second bedroom collapsed when Hurricane Irma struck in 2017. The state provided her with the breeze-blocks she needed to rebuild, but four years later the cement still hasn’t arrived. Her rotting wood ceiling is covered with plastic sheets secured by clothes pegs, but it still leaks when it rains. Her unemployed 33-year-old son, Rolando, was sentenced to 21 years for attacking a police officer during the protests (a charge he denies).

Pedroso has been running a small online campaign to free her son. But shortly after she and seven other local mothers made a video demanding justice , she received a visit from the police, who informed her that the video was being shared on Facebook for “counterrevolutionary” ends.

She has since been questioned by state security, and told that if she takes to the street to protest for her son’s release, she could be charged with public disorder.

Pedroso, a housewife, had applied for a job at Havana’s international airport, to work in immigration. The job was all but in the bag, she said, until she was asked about her son during a final check-up interview. That was September. She hasn’t heard back since.

“Nobody who has a child accused of anything can work in the airport,” she said, before adding, with a touch of gallows humour: “In fact, yes: they can be accused of murder, but not of counterrevolution.”