Pavel Vidal Professor, Pontificia Universidad Javeriana Cali

CUBA STUDY GROUP, February 2018

Complete Article, English: Pavel_Is Cuba’s Economy Ready English

Complete Article, Spanish: Pavel En qué condicion llega la economia cubana a la transicion generacional

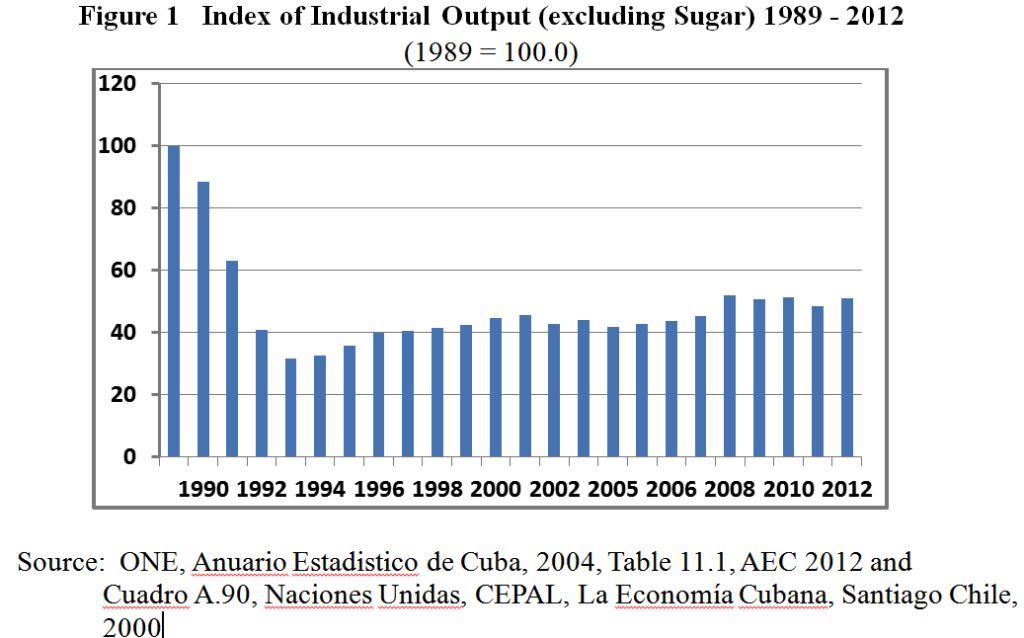

Cuba has changed considerably in these last ten years of economic reforms, though not enough. Family income, tourist services, food production, restaurants, and transportation depend less on the state and much more on private initiative. The real estate market, sales of diverse consumer goods and services, and the supply of inputs for the private sector have all expanded, in formal and informal markets. Foreign investment stands out as a fundamental factor in Cuba’s development. The country has achieved important advances in the renegotiation of its external debts.

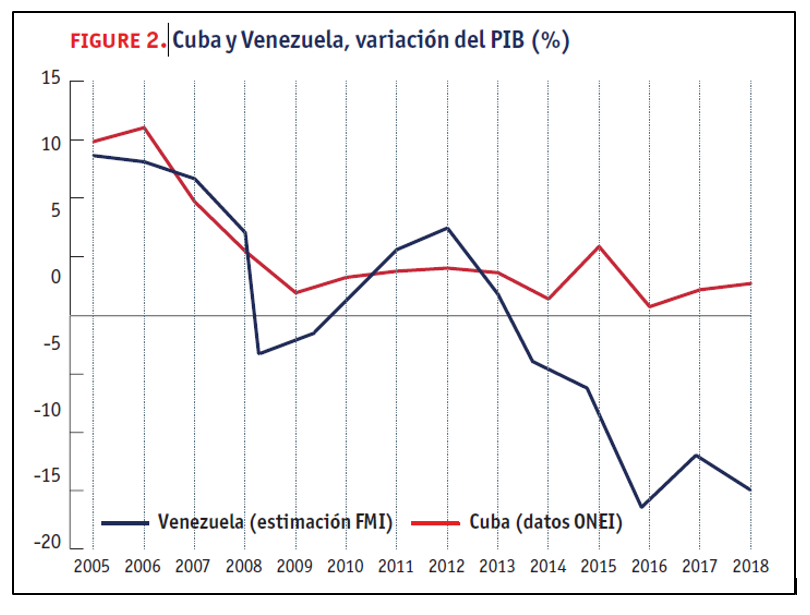

Nevertheless, many other announced changes were defeated by internal resistance, half-heartedly implemented, or put in place in ways that replicated mistakes of the past. The bureaucratic and inefficient state enterprise sector, tied down by low salaries and a strict central plan, impedes economic progress. Cuba’s advantages in education and human capital continue to be underexploited. Neither has the international environment provided much help. The U.S. trade embargo remains in place, the Trump administration has returned to the old and failed rhetoric of past U.S. policies, and Cuba continues to depend on a Venezuelan economy that does not yet seem to have hit rock bottom.

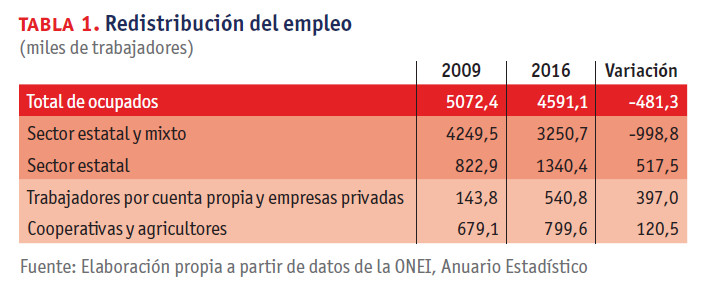

As a consequence, the growth of GDP and productivity has been disappointing, agricultural reform has produced few positive results, and Cuba is once again drowning in a financial crisis. The reforms implemented to date did not create sufficient quality jobs, and, all told, half a million formal positions were eliminated from the labor market.

The second half of 2017 proved especially challenging due to the impacts of Hurricane Irma and new restrictive measures announced by the U.S. government. To these difficulties one must add the decision of the Cuban government to freeze (temporarily) the issuance of licenses to the private sector.

Even so, the National Office of Statistics and Information (ONEI) reported that the economy has not fallen into recession. There are reasons to doubt these statistics, however. Such doubts only multiply when we take into consideration the decision to delay, or altogether avoid, the publication of reports on individual sectors of the economy and the state of the national accounts. For 2018, the government has proposed a rather optimistic economic growth plan (2% increase in GDP) that once again does not appear to appropriately evaluate the complexity of Cuba’s macro-financial environment.

Three highly significant events are anticipated this year: the generational transition within the government, new norms for the private sector, and the beginning of the currency reform process. These three issues have raised expectations on the island, but each may be tackled in a disappointing fashion.

…………………………………..

Conclusions:

Two Other Changes that Could Disappoint A generational transition in the Cuban government will take place on April 19, 2018. Beyond indications that Miguel Díaz-Canel will be the future president, there are no signals as to who will be vice president or who will direct principal ministries such as the Ministry of the Economy or the Ministry of Foreign Relations. Nor do we know where politicians of the “historic generation” will end up.

The new government will want to demonstrate continuity with the former in order to assure its position with various spheres of political power. It appears that the new government will not have its own economic agenda. We can expect that documents approved by recent Congresses of the Cuban Communist Party—which define the limits of reform, the desired development strategy, and the social and economic model to which Cuba aspires—will continue to serve as economic policy guides.

Whatever the composition of the incoming government, in the short term, Cuba’s new leaders will need to convince other state actors that they have the authority and will to, first, achieve the objectives laid out in the “Guidelines for Economic and Social Policy” (Lineamientos), and then deepen the process of reform, overcoming internal forces resistant to change. The new government will thus have to carefully assess the political costs and benefits of implementing reforms to different degrees and at varying speeds, but it will start with low initial political capital due to less popular recognition and a lack of historic legitimacy. Cuba’s new leaders, moreover, must confront these challenges at a time of renewed conflict with the U.S. government. The task is by no means easy, and we will have to wait to see how they handle it.

Another change we can expect this year is the publication of new rules governing the operations of the private sector, and thus unfreezing the issuance of licenses. A greater degree of control over tax payments, as well as efforts to more strongly “bank” the sector, appear to be two basic objectives of the forthcoming rules.

It is very important that the private sector contribute to the Treasury in proportion to its earnings. This is impossible to guarantee if private sector operations are not registered in banks. An effective and progressive tax system provides net dividends to all. The state budget would benefit, exorbitant gaps in income distribution could be avoided, and the societal image of the private sector would be improved. It will be much easier to defeat political and ideological resistance to expansion of the private sector when its income also serves to finance expenses in education and healthcare, and when individual contributions are in line with variable levels of income.

We still do not know if the new rules for the private sector will focus only on fiscal and banking control, or if new policies will address some of the many complaints that the private sector itself has made—high tax rates, the struggle to obtain inputs, and the difficulty of linking operations to foreign trade, for example. A draft of the rules that has circulated does not contain answers to these problems, but rather suggests a focus primarily on more control and penalization.6 If the rules that are ultimately implemented do not differ much from what appears in this draft, depleted prospects for the private sector will be the first disappointment Cubans face in 2018.