By Arch Ritter

Just Published: “Shifting Realities in ‘Special Period’ Cuba”

Archibald R. M. Ritter, Carleton University, Ottawa, Canada

Che’s Afterlife: The Legacy of an Image. By Michael Casey. New York: Vintage Books, 2009. Pp. 388. $15.95 paper. ISBN: 9780307279309.

The Cuba Wars: Fidel Castro, the United States, and the Next Revolution. By Daniel P. Erikson. New York: Bloomsbury Press, 2008. Pp. xiii + 352. $28.00 cloth. ISBN: 9781596914346.

Political Disaffection in Cuba’s Revolution and Exodus. By Sylvia Pedraza. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007. Pp. xix + 359. paper. ISBN: 9780521687294.

Looking Forward: Comparative Perspectives on Cuba’s Transition. Edited by Marifeli Pérez-Stable. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 2007. Pp. xx + 332. $27.00 paper. ISBN: 9780268038915.

Cuba in the Shadow of Change: Daily Life in the Twilight of the Revolution. By Amelia Rosenberg Weinreb. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2009. Pp. 272. $69.95 cloth. ISBN: 9780813033693.

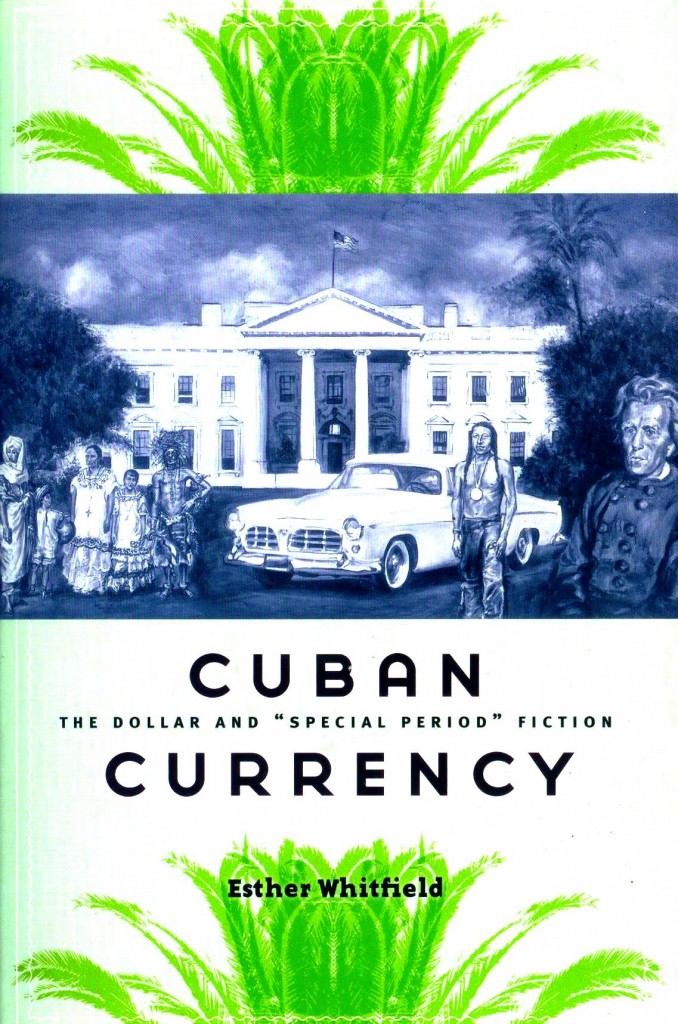

Cuban Currency: The Dollar and Special Period Fiction. By Esther Whitfield. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2008. Pp. 217. $22.50 paper. ISBN: 9780816650378.

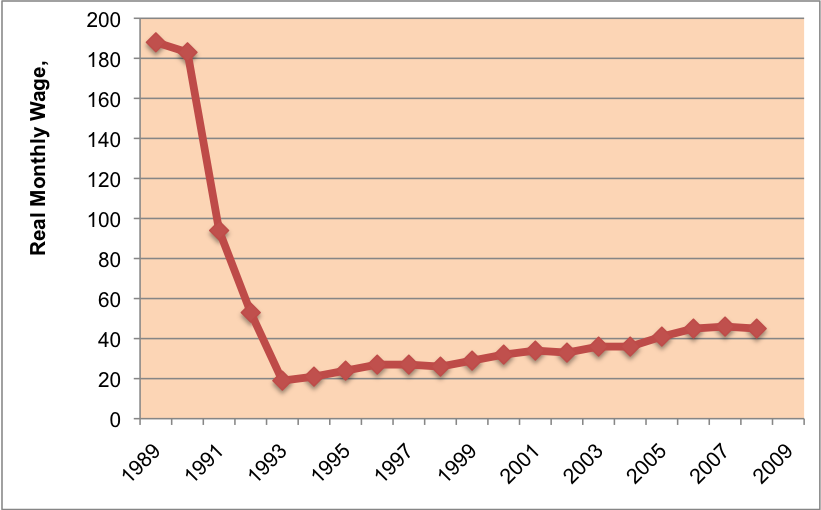

Revolutionary Cuba’s Golden Age ended in 1988-1990 when the former Soviet Union adopted world prices in its trade with Cuba, ceased new lending, and discontinued its subsidization of the Cuban economy. The result was the economic meltdown of 1989-1994. In1992, President Fidel Castro labeled the new époque the “Special Period in Time of Peace,” a title that has lasted almost two decades as of 2010. Many outside observers have imagined that Cuba would in time follow the countries of Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union in making a transition toward a more market-oriented economic system and perhaps a Western style of pluralistic democracy. This has not happened. The modest economic changes of the early1990s have not led to sustained reform. Political reform has been almost undetectable. At times, rapid change has seemed inevitable and imminent. But at others, it has appeared that gerontocratic paralysis might endure well into the 2010s. Change will undoubtedly occur, but its trajectory, timing, and character are difficult if not impossible to predict. When a process of transition does arrive, it will likely be unexpected, confused, and erratic, and will probably not fit the patterns of Eastern Europe, China, or Vietnam.

The books included in this review focus mainly on changing realities during the Special Period and the nature of prospective change. They constitute a valuable contribution to our understanding of a range of dimensions of Cuba’s existence in this era which in fact is not “special” but is instead the “real world”.

The collection edited by Marifeli Pérez-Stable assumes that a transition will occur and asks what useful insights may be gleaned from the experiences of other Latin, Eastern European, Asian, and Western European countries. The analyses included in the collection constitute the best exploration of the key aspects of Cuba’s possible alternative futures yet available. Then Daniel P. Erikson examines the U.S.-Cuban relationship together with domestic U.S. policies toward Cuba during the Special Period, concluding with a chapter on “The Next Revolution.” His popular historical analysis also is probably the best available as well as most readable review of this tragically dysfunctional relationship.

The culture of the silent majority or “shadow public” is the focus of Amelia Weinreb. This sociological-anthropological analysis of Cuba’s silent majority fills a major vacuum in works on Cuba over the last 20 years, focusing as it does on the character, aspirations and behavior of a group that has been almost ignored even though it probably constitutes a majority of the population of Cuba. Sylvia Pedraza examines Cuba’s evolving domestic political situation and the consequences for emigration over the last half century, including the two decades of the Special Period. Her work is probably the seminal analysis of the motivations underlying and patterns of Cuba’s continuing emigration hemorrhage.

Michael Casey examines how the Cuban government has capitalized on Che Guevara’s “brand”—epitomized by the iconic photograph by Alberto Korda—and how Che’s image has been commercialized for both political and financial motivations, using property and trademark law, and the marketing mechanisms of the international capitalist system. While perhaps outside the common purview of mainstream social science research on Cuba, Casey’s examination of the Korda-Che image provides a novel and convincing examination of how the Cuban political regime has sought to commercialize the central martyr of the Revolution. Finally, Esther Whitfield explores cultural and literary changes in Cuba’s world of fiction during the Special Period. Her work is also ground-breaking in examining the impacts of the economic realities of the two-currency pathology on the incentive structure and orientation of Cuban writers of fiction.

Marifeli Pérez-Stable has assembled an all-star cast of authors to produce yet another fine contribution to our understanding of Cuba and its current situation.[1] Looking Forward aims to investigate the alternatives facing Cuba after a possible regime change or “poof moment”—as Jorge Domínguez puts it (7 and 61) —when such change might occur, as if by magic. The authors were asked to examine their particular areas of expertise for insights from other democratizing processes, the particular relevance of the conditions of the Special Period, and the “plausible and/or desirable alternatives . . . for a Cuba in transition” (7). Given the concision and richness of the twelve essays in this book, it is difficult if not impossible to outline and critique them in the detail that each of them merits in a brief review. All are substantively first-rate.

In opening, Pérez-Stable assumes that “a medium-term democratic transition is likely in Cuba though not certain” (19). She explores first the transitions of Eastern and Central Europe and Latin America for insights into the Cuban case, and second, the possible roles in a post-Fidel Castro Cuba of the Communist Party, the National Assembly, and the Association of Combatants of the Cuban Revolution, Cuba’s veterans’ organization. Her central conclusion is that a hybrid regime is most probable, in which elements of marketization and some liberalization combine with continued authoritarianism.

In his examination of military-civil relations, Jorge Domínguez is reasonably optimistic that further downsizing of the Cuban military will occur with the normalization of U.S.-Cuban relations. He also argues that the military will be compatible with democratization under the last three of the four scenarios that he explores: 1. a dynastic succession with continued Communist Party monopoly and a market economy opening; 2. with removal of the external threat, the military could focus on internal security only; 3. the previous scenario, but with a stronger military to maintain public order in the face of serious domestic security threats; and 4. the second scenario again but with a major continuing role for professional armed forces for international peace-keeping. (61-70).

Gustavo Arnavat analyzes the legal and constitutional dimensions of moving toward representative democracy and a market economy, and argues that major constitutional amendments or a new constitution approved by referendum will be necessary.

Damián Fernández presents a thought-provoking and sobering analysis of the role of civil society, emphasizing the difficulty of political reengagement and the development of attitudes supporting participatory citizenship. Mala Htun puts forward a well-balanced discussion of Cuba’s achievements and lingering problems in the same area of transition politics, and of the impacts of the Special Period on women and gender equality. She concludes that “[a]chieving gender justice . . . requires greater economic growth and political reforms” (137). Alejandro de la Fuente also outlines the achievements of Cuba since 1959 and some of the setbacks for Afro-Cubans since 1990; these include a smaller share of remittances and relatively less employment in tourism and high-end self-employment. His main conclusion is that special antidiscrimination policies will be necessary in the transition to a market economy. Jorge Pérez-Lopez contributes a fine analysis of the economic policy reforms needed for transition. In his first-rate essay, Carmelo Mesa-Lago carefully reviews the impacts of the Special Period on social welfare—education, health, social services, poverty, and income equality—and outlines the range of policy approaches needed if Cuba is to maintain social justice while providing incentives to economic improvement.

Corruption has been a curse for Cuba since Independence. It has evolved in unique ways there since 1990, and has tended to escalate seriously in Eastern European transitions, as Dan Erikson shows in his contribution to Looking Forward. The politically complex and difficult role of Cuban émigrés in any future transition is addressed by Lisandro Pérez, though perhaps not with due emphasis on how Cuban-Americans are likely to contribute to institutional development, trade linkages, investment projects, return migration, and tourism. Rafael Rojas provides an insightful exploration of the psychological and political transformations that must occur in this same area, in which polarized and implacable enemies— each claiming ownership of historical interpretation—must become loyal adversaries, competing yet cooperating within democratic rules. Finally, William LeoGrande provides a superb survey of U.S.-Cuban relations during the Special Period and of U.S. relations with former adversaries, so as to address the future dealings of the two neighbors.

In its entirety, this fine volume sets a high standard that will be difficult to surpass. What one would also like to see, however, is another chapter on how Cuba might get to and through a transition to achieve genuine democracy and a mixed-market economy. One might also question the editor’s decision against the citation of sources so as to reach a broader, less academic audience. This book should indeed reach a wide public, but the absence of the citations hardly seems necessary for that purpose.

In a market well supplied with books and reports on U.S.-Cuba relations, Erikson’s The Cuba Wars is perceptive, objective, and engaging. His work is based on general political analysis from his vantage point at the Inter-American Dialogue in Washington; on interviews with many key players on Cuban issues in Miami, the U.S. Congress, the policy community, and academics; and on his own knowledge of Cuba, attained in many visits to the island in the past decade. For those who have lived through the U.S.-Cuba relationship over the last decade or the last 50 years, Erikson’s discussion will be enjoyable as well as insightful. His narrative style is captivating and brings again to life various events at the center of U.S.-Cuban interaction: events such as the Elián González affair, the tenure of James Cason as chief of the U.S. Interests Section, Cuba’s shooting down of an aircraft operated by Brothers to the Rescue, the conviction of Cuban spy Ana Belén Montes, the “Five Cuban Heroes,” and the eviction of Cubans from a hotel in Mexico City by the U.S. Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Asset Control. Erikson’s discussions of the Chávez/Venezuela-Castro/Cuba relationship, the Cuban-American Community in Miami, and the pressures promoting and obstructing a greater role for market mechanisms in Cuba are all captivating and substantive. His vignettes of congressmen and women with important roles in policymaking with respect to Cuba are fascinating. If I have any quibbles with the book, it is with the title which seems over-amplified, as there has not been a war between the two countries. The “Next Revolution” referred to in the title is not impossible, but I would think that a difficult but orderly evolution toward Western-style participatory democracy, and a more centrist form of economic organization, are more probable.[2]

In a market well supplied with books and reports on U.S.-Cuba relations, Erikson’s The Cuba Wars is perceptive, objective, and engaging. His work is based on general political analysis from his vantage point at the Inter-American Dialogue in Washington; on interviews with many key players on Cuban issues in Miami, the U.S. Congress, the policy community, and academics; and on his own knowledge of Cuba, attained in many visits to the island in the past decade. For those who have lived through the U.S.-Cuba relationship over the last decade or the last 50 years, Erikson’s discussion will be enjoyable as well as insightful. His narrative style is captivating and brings again to life various events at the center of U.S.-Cuban interaction: events such as the Elián González affair, the tenure of James Cason as chief of the U.S. Interests Section, Cuba’s shooting down of an aircraft operated by Brothers to the Rescue, the conviction of Cuban spy Ana Belén Montes, the “Five Cuban Heroes,” and the eviction of Cubans from a hotel in Mexico City by the U.S. Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Asset Control. Erikson’s discussions of the Chávez/Venezuela-Castro/Cuba relationship, the Cuban-American Community in Miami, and the pressures promoting and obstructing a greater role for market mechanisms in Cuba are all captivating and substantive. His vignettes of congressmen and women with important roles in policymaking with respect to Cuba are fascinating. If I have any quibbles with the book, it is with the title which seems over-amplified, as there has not been a war between the two countries. The “Next Revolution” referred to in the title is not impossible, but I would think that a difficult but orderly evolution toward Western-style participatory democracy, and a more centrist form of economic organization, are more probable.[2]

In Cuba in the Shadows, Amelia Rosenberg Weinreb (Anthropology, University of Texas at Austin) explores and analyzes the lives, behavior, and views of “ordinary Cubans.”[3] These Cubans are familiar to those who have come to know Cuba during the Special Period. They probably constitute a large majority of the population. These “unsatisfied citizen-consumers,” as Weinreb calls them (2 and 168.), strive to survive with some access to basic “modern” goods, above and beyond what the ration book provides in an amount insufficient for life maintenance since 1990. These modern goods perhaps include some luxuries, but they also include basics such as toilet paper and women’s hygiene products that are available only in the “dollar stores” or tiendas de recaudación de divisas (stores for the collection of foreign exchange). This “silent majority” has remained under-analyzed and largely ignored by scholars, perhaps—as Weinreb suggests—because they do not seem to merit special attention relative to indigenous peoples, the poor, or labor unions, or perhaps because they do not fit the orientations of New Social Movement and Structuralist Marxist approaches.

Weinreb’s ethnographic participant observation succeeds in producing an analysis from about as deep within Cuban realities as it is possible for an outsider to get. Her success can be attributed in part to her research assistants and neighborhood ambassadors, namely her three young children, Maya, Max, and Boaz, who helped to establish rapport, friendship, and shared parenting bonds with Cubans who empathized and wanted to help a young mother. This “family fieldwork” provides a unique window into Cuban society and the lives of Cubans.

Weinreb’s focus is a “shadow public,” somewhat analogous to the shadow economy, as the following explains:

[U]nsatisfied citizen-consumers . . . share interests, characteristics, a social imagery and practice, but their political silence, underground economic activity, and secret identity as prospective migrants casts a shadow over them. They are therefore a shadow public, an un-coalesced but powerful group that engages in resistance to state domination but without a public sphere, and only in ways that will allow them to remain invisible while maintaining or improving their families’ economic welfare. (168)

The roots of the shadow economy of course predate the Revolution, indeed going back to the colonial period and its unofficial economy of smuggling and contraband, as reflected in the expression obedezco pero no cumplo (I obey but do not comply). However, the expansion and pervasiveness of today’s shadow economy were generated by the character of central planning itself, and by the circumstances of the Special Period, as analyzed in chapter 1. Chapters 2 and 3 examine how citizens strive to maintain private space and personal control within the context of the state’s domination of personal life and economic activity. Chapters 4-6 explore a range of survival strategies. Chapter 4 focuses on the concepts and practices encapsulated by the terms resolver, luchar, conseguir, and inventar, each with unique connotations in the context of the Special Period. The significance of material things—and the lack thereof—are investigated in chapter 5. Chapter 6 treats the importance of access to foreign exchange or “convertible pesos.” Weinreb here presents a Cuban class system that puts the “red bourgeoisie” at the top, followed by artists with privileged access to travel and foreign exchange earnings, “dollar dogs” or cuenta propistas (own-account workers) with access to tourist expenditures or remittances from relatives or friends abroad, “unsatisfied citizen consumers,” and finally, at the bottom, the “peso poor” who lack access to foreign exchange and additional earnings. The final chapters examine the broad-based phenomenon of feeling trapped and the dream of escape via emigration. Chapter 8 explores “off-stage” expressions of dissatisfaction, criticism, and resistance, which remain purposely hidden, unorganized, and outside public space. This state of affairs may be changing, however, with the Damas en Blanco and bloggers courageously breaking into the public arena, spearheaded by Yoani Sánchez. Finally, chapter 9 draws together the strands of Weinreb’s analysis and explores the relevance of the concepts of shadow public and unsatisfied citizen-consumer in the broader context of Latin America.

Weinreb succeeds admirably in describing and analyzing Cuba’s silent majority, those “ordinary outlaws” who are decent, hard-working, entrepreneurial, and ethical, yet must defend themselves and their survival through a myriad of economic illegalities within the framework of a dysfunctional economic system. These people live within the doble moral, effectively cowed into acquiescence by a political system whose main escape valve is criticism, innocuous at first, but then increasingly bitter, followed by emigration. The shadow public perhaps constitutes a potential “shadow opposition,” but seems to be easily contained and controlled by the governments of the Castro brothers. One might conclude from Weinreb’s work that this population—currently disengaged and thinking incessantly about emigration—is ripe for public reengagement and that in time there may occur a surprisingly rapid mobilization for change.

Weinreb’s analysis raises some additional questions. Under what circumstances might a shadow opposition become organized, finding a strong voice to become a real opposition? Will the new citizen-journalists of Cuba’s blogging community—plus critics such as Vladimiro Roca, Oscar Espinosa Chepe, Marta Beatriz Roque, Elizardo Sánchez, the Damas en Blanco, and some Catholic organizations—be able to break the control of the Communist Party and the current leadership? Will normalization of relations with the United States and the ending of the “external threat”—a siege mentality long used as a pretext for denying basic political liberties—further erode control of the Party and create new political alignments within Cuba?

Like the flag raised by Máximo Gómez in Cuba’s struggle for independence but sewn by Victoria Pedraza, her grandaunt, Sylvia Pedraza (Sociology, University of Michigan) intends her book to be a contribution to Cuban history. Political Disaffection in Cuba’s Revolution and Exodus, Pedraza’s magnum opus so far, is indeed a splendid contribution. It examines the political, social, and economic history of Revolutionary Cuba, exploring its impact on citizens and on emigration decisions and patterns from 1959 to midway through the first decade of the present century. The scope of the work of course goes beyond the Special Period, whose emigrants are the most recent product of a series of four waves from Revolutionary Cuba, following those of 1959-1962, 1962-1979, and 1979-1989.[4] These emigrations serve as organizing periods for Pedraza, who offers a careful reading of the history of the Revolution, using participation and observation from within the Cuban-American community and among Cubans on the island, 120 in-depth structured interviews with a representative selection of émigrés from 1959 to 2004, personal documents of émigrés, and census and polling information. Of special interest in this engaging and moving mix (which few academics manage to achieve) are Pedraza’s personal odyssey and insights as a child of the Revolution, quasi-Peter Pan émigré, and returnee with the Antonio Maceo Brigade in 1979. The account of her reunification with an extended family that she had not seen since leaving Cuba is particularly poignant.

Like the flag raised by Máximo Gómez in Cuba’s struggle for independence but sewn by Victoria Pedraza, her grandaunt, Sylvia Pedraza (Sociology, University of Michigan) intends her book to be a contribution to Cuban history. Political Disaffection in Cuba’s Revolution and Exodus, Pedraza’s magnum opus so far, is indeed a splendid contribution. It examines the political, social, and economic history of Revolutionary Cuba, exploring its impact on citizens and on emigration decisions and patterns from 1959 to midway through the first decade of the present century. The scope of the work of course goes beyond the Special Period, whose emigrants are the most recent product of a series of four waves from Revolutionary Cuba, following those of 1959-1962, 1962-1979, and 1979-1989.[4] These emigrations serve as organizing periods for Pedraza, who offers a careful reading of the history of the Revolution, using participation and observation from within the Cuban-American community and among Cubans on the island, 120 in-depth structured interviews with a representative selection of émigrés from 1959 to 2004, personal documents of émigrés, and census and polling information. Of special interest in this engaging and moving mix (which few academics manage to achieve) are Pedraza’s personal odyssey and insights as a child of the Revolution, quasi-Peter Pan émigré, and returnee with the Antonio Maceo Brigade in 1979. The account of her reunification with an extended family that she had not seen since leaving Cuba is particularly poignant.

In Che’s Afterlife, Michael Casey follows Korda’s famous photograph of a Christ-like Ernesto “Che” Guevara into the consciousness of people around the world. This image is a well-defended and trademarked icon (copyright VA-1-276-975) owned by Korda’s daughter, Diana Díaz, and used in collaboration with the government of Cuba. For some, it is a quasi-spiritual symbol of hope for a better future; for others, a symbol of undefined but earnest youthful rebellion; and for still others, an abhorrent symbol of authoritarianism. Casey, a Dow Jones Newswire bureau chief in Buenos Aires, has written an intriguing history of the image’s trajectory over the last half century. He brings together research into the lives of both Korda and Guevara, a command of the history of Revolutionary Cuba, knowledge of countries where the Guevara mythology is important, an understanding of copyright law, and original investigative interviewing and reporting.

Casey begins with the instant when the photo was taken on 5 March 1960. He sketches Che’s role in the new government—notably as chief of La Cabaña prison and overseer of the swift executions of prisoners—his secretive and disastrous Congo operation, and his guerrilla campaign in Bolivia, putting the launch of Che as icon and of the “Heroic Revolutionary” brand at the 18 October 1967 memorial ceremony at the Plaza de la Revolución. Casey also presents an account of Korda’s activities in Havana, the first publications of his photograph, and the cultural ferment of the early years of the Revolution, followed by the disillusionment of many in the mid-1960s. He traces the peregrinations of Korda’s Che through Argentina, Bolivia, Venezuela, and Miami, as well as in the student ferment of 1968 from Paris to Berkeley. His later chapters focus on the use of Che’s image as a brand by the government of Cuba; here, it no longer signifies a heroic guerrilla promoting revolution, but has instead become an advertisement, selling Cuba in the international tourist marketplace. The essence of the image ia now “the idea of revolutionary nostalgia” (306). After some thirty-seven years during which the photograph was freely available for use by anyone, copyright ownership now applies and control is exercised through legal means when necessary.

Casey takes us on a fascinating journey through the life and afterlife of Che and through a half century of international social and political history, using Che’s image as a prism. His book should find a wide readership, of all political stripes, who have an interest in Cuba or in major political and social movements. Those with interests in marketing, branding, and copyright law will also find this volume illuminating.

I must confess that when I agreed to include Cuban Currency: the Dollar and Special Period Fiction in this review, I thought it was an analysis of Cuba’s monetary system, not having read the title carefully. To my initial trepidation, Esther Whitfield focuses instead on literature, but in the context of Cuba’s dual-currency pathology. Her survey of recent fiction has turned out to be a delight, even for an economist with little direct knowledge of Cuban literature.

I must confess that when I agreed to include Cuban Currency: the Dollar and Special Period Fiction in this review, I thought it was an analysis of Cuba’s monetary system, not having read the title carefully. To my initial trepidation, Esther Whitfield focuses instead on literature, but in the context of Cuba’s dual-currency pathology. Her survey of recent fiction has turned out to be a delight, even for an economist with little direct knowledge of Cuban literature.

Whitfield’s central argument is that the Special Period generated a boom in cultural exports, including literature, due to the opening of Cuba’s economy and society, the subsequent expansion of international tourism and the popularity of all things Cuban, the decriminalization of the use of the dollar, its adoption as a legal currency, and its quick ascent to supremacy over the “old peso.” Special Period literature then became market-driven—like many other activities in Cuba—with authors’ incomes dependent on foreign sales and hard-currency contracts, rather than on Cuba’s literary bureaucracy and membership in the writers’ union. The dominance of the foreign market was further strengthened by the shrinkage of the domestic peso market for books because of declining incomes. This new foreign-market orientation was formalized by legislation in 1993 that permitted authors to negotiate their own contracts with foreign publishing houses and to repatriate their royalties under a relatively generous tax regime. Like other Cuban citizens, authors responded quickly to these new incentives. Special Period fiction is set in a “real Cuba” of interest to foreigners, namely in the Cuba of a behavior-warping dual-currency system, urban decay, dysfunctional Soviet-style economy, and political gerontocracy, together with a vibrant Afro-Latin culture and time-immemorial tropical eroticism. Ironically, the international boom in Cuban fiction during the sunset of the Revolution was a sequel to the literary boom of the 1960s, which was set in the confidence and vigor of the youthful Revolution.

Whitfield begins with an analysis of the circumstances of the Special Period that pushed authors into an external orientation. She then focuses on the works of Zoé Valdés, especially her award-winning I Gave You All I Had (1966), published in exile in Paris, which allows Whitfield to trace the central role played by a U.S. one dollar bill and its symbolic relevance for the culture of the Special Period. Short stories are the subject of the next chapter, with particular attention to the work of Ronáldo Menéndez. His story, entitled “Money,” is also set in the world of the doble moneda and doble moral, but criticizes the reliance on foreign markets and worries about the jineterización (translated imperfectly as “prostituting”) of the writer-publisher relationship and possible debasement of “true” Cuban literature. Whitfield goes on to examine the work of Pedro Juan Gutiérrez, notably the five books of his Ciclo Centro Habana. Gutiérrez writes for a foreign readership, but also critiques it, placing the reader in the position of voyeur into the “lives of sexual disorder, moral depravity and economic despair” of Havana (98). In her final chapter Whitfield meditates on artists’ depictions of Cuba’s urban decay and on critical analyses of such depictions.

Whitfield has produced a fine analysis of how economic circumstances generated new problems and new possibilities for Cuban authors, who have risen to the challenge and produced a literature of broad international appeal. Whitfield’s writing is engaging, her knowledge seems profound, and her subject is enchanting. However, I am not a competent critic of Cuban literature or literary criticism, and cannot tender a confident evaluation of its value for scholars in these fields. Her book, linking socio-politico-economic circumstances of the Special Period to Cuban literature, will nevertheless interest a broad range of social scientists, as well as the more literary-minded.

Is the international market for Cuban fiction as transitory as one might expect or hope that the Special Period itself may be? Perhaps. It may be that when Cuba escapes the Special Period and becomes a “normal country” with a normal monetary system, the special interest in its literary portrayal may diminish. However, the difficulties of economic and political reform are likely to continue for some time, and are likely to take various twists and turns that will hold our interest for some time to come. I hope that Cuba’s fiction writers are there to illuminate the process for a world readership.

[1] Full disclosure: I served as an evaluator for Marifeli Perez-Stable’s edited collection Looking Forward for the University of Notre Dame Press. [2] One minor detail: Fidel Castro’s hometown was not Bayamo but Birán, not far from Cueto and Mayarí, both immortalized in the song “Chan Chan” by the Buena Vista Social Club. [3] I also served as a reader for the Universities Press of Florida for the original manuscript of this volume. I was as impressed with it then as I am now. [4] The emigrations of 1979-1989 were sparked in part by the return visits of Cuban Americans, who turned out not to be gusanos (worms)—the dehumanizing label given to them by the Cuban government—but instead mariposas (butterflies), as they were relabeled with typical Cuban humor.