BY YOANI SÁNCHEZ

This essay was originally published in Foreign Policy, October 12, 2011. It can be found here: “ Country for Old Men” or here: http://www.foreignpolicy.com/articles/2011/10/11/country_for_old_men

At the end of his July 31, 2006, broadcast, the visibly nervous anchor on Cuban Television News announced that there would be a proclamation from Fidel Castro. This was hardly uncommon, and many Cubans no doubt turned off their TVs in anticipation of yet another diatribe from thecomandante en jefe accusing the United States of committing some fresh evil against the island. But those of us who stayed tuned that evening saw, instead, a red-faced Carlos Valenciaga, Fidel’s personal secretary, appear before the cameras and read, voice trembling, from a document as remarkable as it was brief. In a few short sentences, the invincible guerrilla of old confessed that he was very ill and doled out government responsibilities to his nearest associates. Most notably, his brother Raúl was charged with assuming Fidel’s duties as first secretary of the Communist Party’s Central Committee, commander in chief of the Revolutionary Armed Forces, and president of the Council of State. The dynastic succession had begun.

It was a miracle that the old telephone exchanges, with their 1930s-vintage equipment, didn’t collapse that night as callers rushed to share the news, in a code that was secret to no one: “He kicked the bucket.” “El Caballo” — the Horse — “is gone.” “The One is terminal.” I picked up the receiver and called my mother, who was born in 1957, on the eve of Castro’s revolution; neither of us had known any other president. “He’s not here anymore, Mom,” I said, almost whispering. “He’s not here anymore.” On the other end of the line she began to cry.

It was the little things that changed at first. Rum sales increased. The streets of central Havana were oddly empty. In the absence of the prolific orator who was fond of cutting into TV shows to address his public, homemakers were surprised to see their Brazilian soap operas air at their scheduled times. Public events began to dwindle, among them the so-called “anti-imperialism” rallies held regularly throughout the country to rail against the northern enemy. But the fundamental change happened within people, within the three generations of Cubans who had known only a single prime minister, a single first secretary of the Communist Party, a single commander in chief. With the sudden prospect of abandonment by the papá estado — “daddy state” — that Fidel had built, Cubans faced a kind of orphanhood, though one that brought more hope than pain.

Five years later, we have entered a new phase in our relationship with our government, one that is less personal but still deeply worshipful of a man some people now call the “patient in chief.” Fidel lives on, and Raúl — whose power, as everyone knows, comes from his genes rather than his political gifts — has ruled since his ultimate accession in February 2008 without even the formality of the ballot box, prompting a dark joke often told in the streets of Havana: This is not a bloody dictatorship, but a dictatorship by blood. Pepito, the mischievous boy who stars in our popular jokes, calls Raúl “Castro Version 1.5” because he is no longer No. 2, but still isn’t allowed to be the One. When the comandante — now barely a shadow of his former self — appeared at the final session of the Communist Party’s sixth congress this April, he grabbed his brother’s arm and raised it, to a standing ovation. The gesture was intended to consecrate the transfer of power, but to many of us the two old men seemed to be joining hands in search of mutual support, not in celebration of victory.

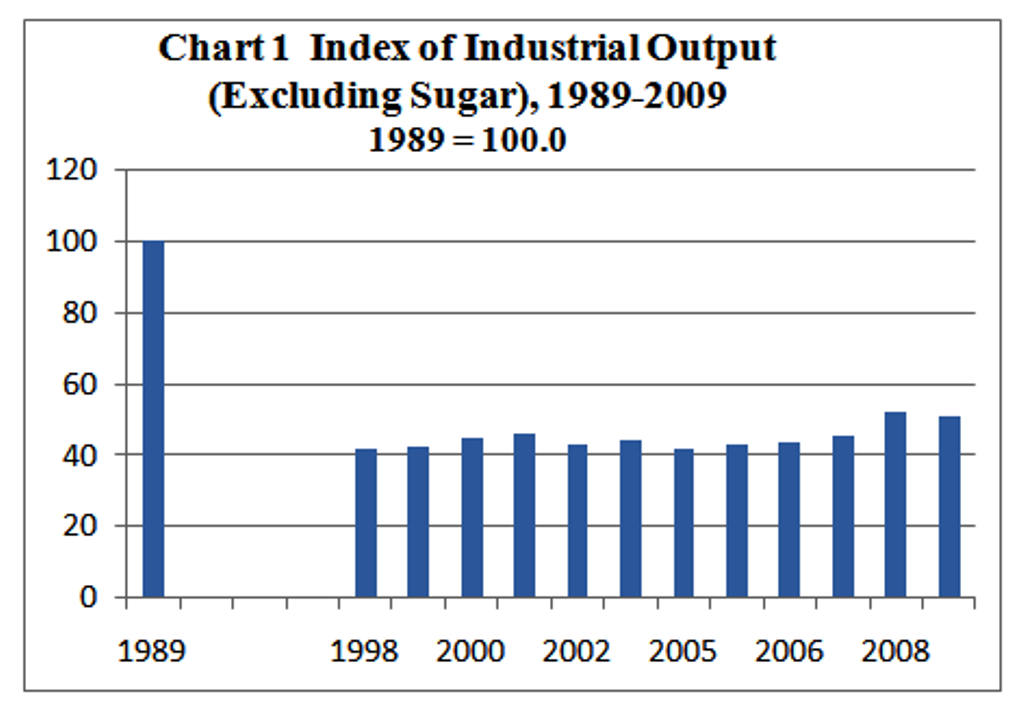

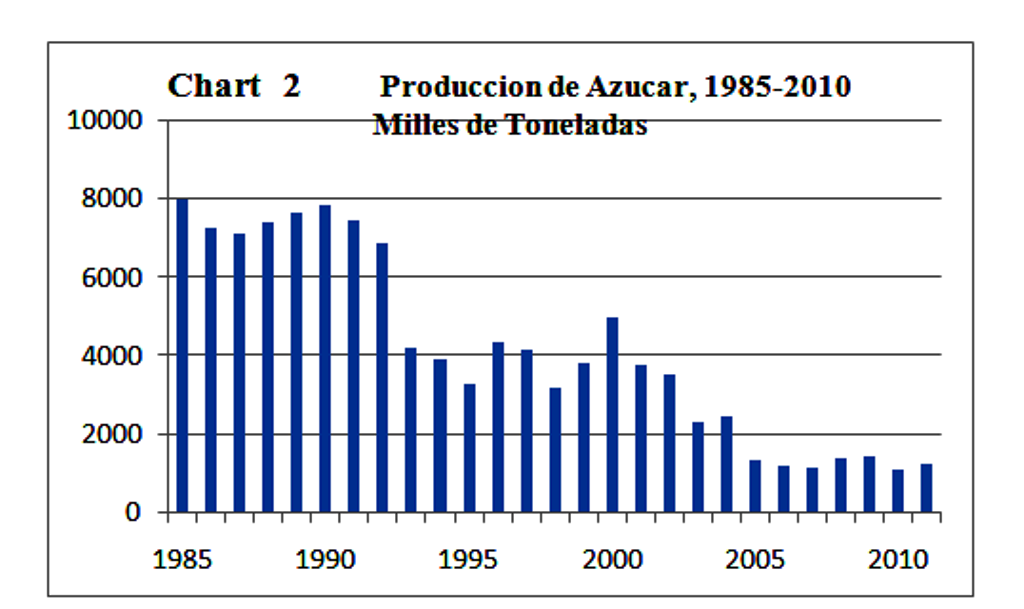

Raúl’s much-discussed reforms followed the supposed handover of power, but in reality, they have been less steps forward than attempts to redress the legal absurdities of the past. One of these was the lifting of the tourist apartheid that prevented Cubans from enjoying their own country’s hotel facilities. For years, to connect to the Internet, I had to disguise myself as a foreigner and mumble a few brief sentences in English or German to buy a web-access card in the lobby of some hotel. The sale of computers was finally authorized in March 2008, though by that time many younger Cubans had assembled their own computers with pieces bought on the black market. The prohibition on Cubans having cell-phone contracts was also repealed, ending the sad spectacle of people begging foreigners to help them establish accounts for prepaid phones. Restrictions on agriculture were loosened, allowing farmers to lease government land on 10-year terms. The liberalization brought to light the sad fact that the state had allowed much of the country’s land (70 percent of it was in state hands) to become overgrown with invasive weeds.

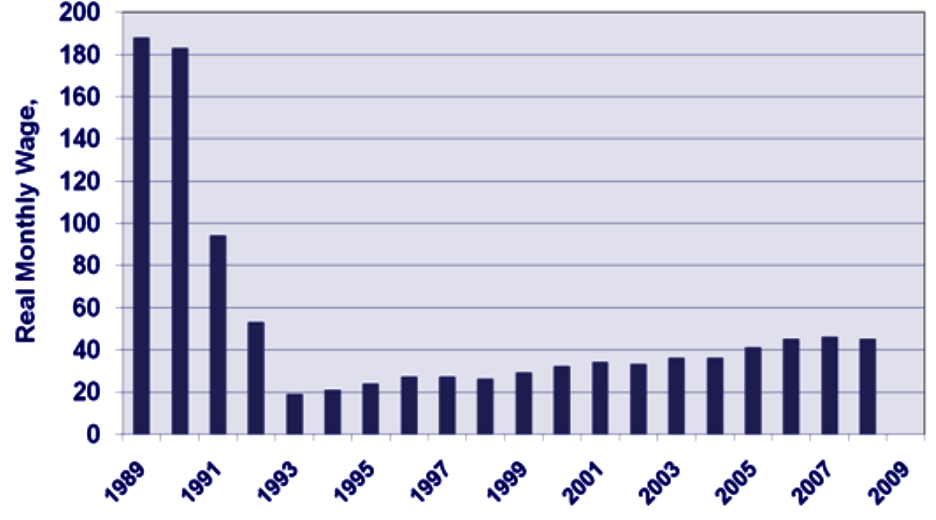

While officially still socialist, the government has also pushed for an expansion of so-called self-employment, masked with the euphemism of “nonstate forms of production.” It is, in reality, a private sector emerging in fits and starts. In less than a year, the number of self-employed grew from 148,000 to 330,000, and there is now a flowering of textile production, food kiosks, and the sale of CDs and DVDs. But heavy taxes, the lack of a wholesale market, and the inability to import raw materials independent of the state act as a brake on the inventiveness of these entrepreneurs, as does memory: The late 1990s, when the return to centralization and nationalization swept away the private endeavors that had surged in the Cuban economy after the fall of the Berlin Wall, were not so long ago.

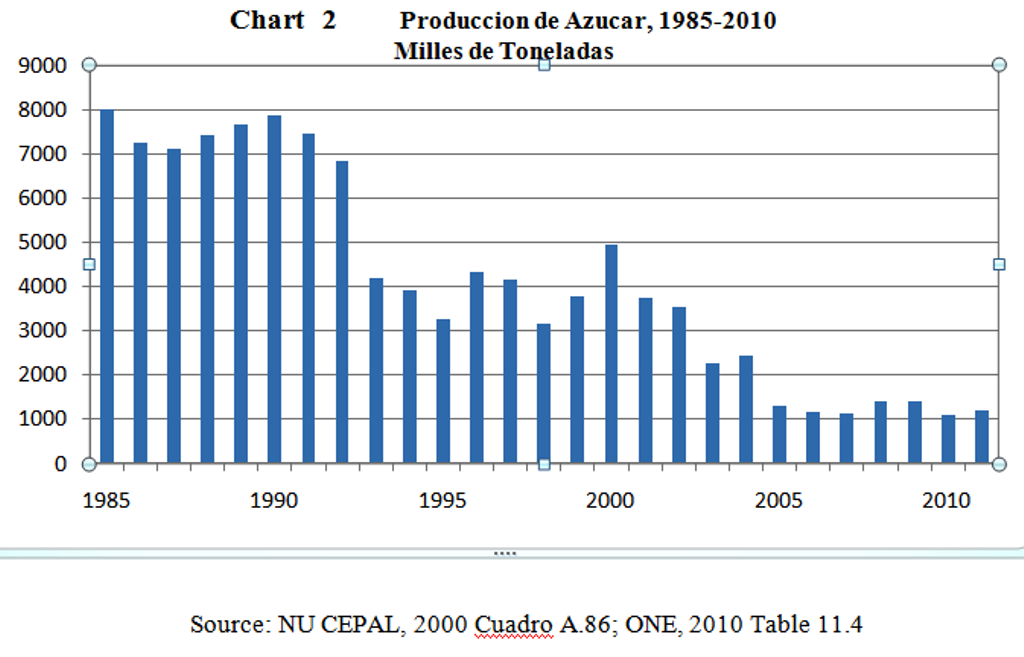

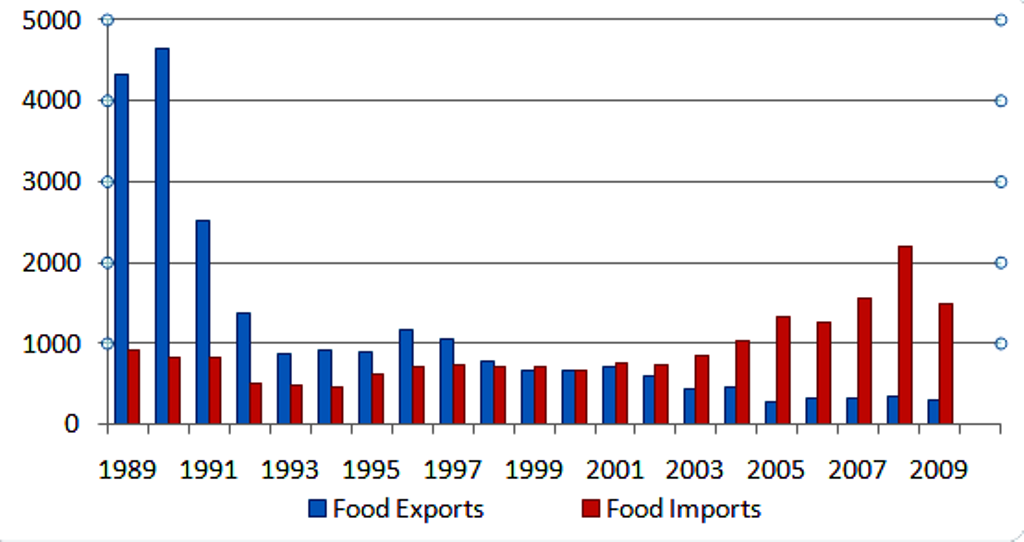

So for now, the effects of the highly publicized reforms are barely noticeable on our plates or in our pockets. The country continues to import 80 percent of what we consume, at a cost of more than $1.5 billion. In the hard-currency stores, the cans of corn say “Made in the USA”; the sugar provided through the ration book travels from Brazil; and in the Varadero tourist hotels, a good part of the fruit comes from the Dominican Republic, while the flowers and coffee travel from Colombia. In 2010, 38,165 Cubans left the island for good. My impatient friends declare they are not going to stay “to turn off the light in El Morro” — the lighthouse at the entrance to Havana Bay — “after everyone else leaves.”

The new president understands all too well that transformations that are too deep could cause him to lose control. Cubans jokingly compare their political system to one of the dilapidated houses in Old Havana: The hurricanes don’t bring it down and the rains don’t bring it down, but one day someone tries to change the lock on the front door and the whole edifice collapses. And so the government’s most practiced ploy is the purchase of time with proclamations of supposed reforms that, once implemented, fail to achieve the promised effects.

But this can only continue for so long. Before the end of December, Raúl Castro will have to fulfill his promise to legalize home sales, which have been illegal since 1959, a move that will inevitably result in the redistribution of people in cities according to their purchasing power. One of the most enduring bastions of revolutionary imagery — working-class Cubans living in the palatial homes of the bygone elite — could collapse with the establishment of such marked economic differences between neighborhoods.

And yet the old Cuba persists in subtle, sinister forms. Raúl works more quietly than Fidel, and from the shadows. He has increased the number of political police and equipped them with advanced technology to monitor the lives of his critics, myself among them. I learned long ago that the best way to fool the “security” is to make public everything I think, to hide nothing, and in so doing perhaps I can reduce the national resources spent on undercover agents, the pricey gas for the cars in which they move, and the long shifts searching the Internet for our divergent opinions. Still, we hear of brief detentions that include heavy doses of physical and verbal violence while leaving no legal trail. Cuba’s major cities are now filled with surveillance cameras that capture both those who smuggle cigars and those of us who carry only our rebellious thoughts.

But over the last five years the government has undeniably and irreversibly lost control of the dissemination of information. Hidden in water tanks and behind sheets hanging on clotheslines, illegal satellite dishes bring people the news that is banned or censored in the national media. The emergence of bloggers who are critical of the system, the maturation of independent journalism, and the rise of autonomous spaces for the arts have all eroded the state’s monopoly on power.

Fidel, meanwhile, has faded away. He appears rarely and only in photos, always dressed in the tracksuit of an aging mafioso, and we begin to forget the fatigues-clad fighting man who intruded on nearly every minute of our existence for half a century. Just a year ago, my 8-year-old niece was watching television and, seeing the desiccated face of the old commander in chief, shouted to her father, “Daddy, who is this gentleman?”