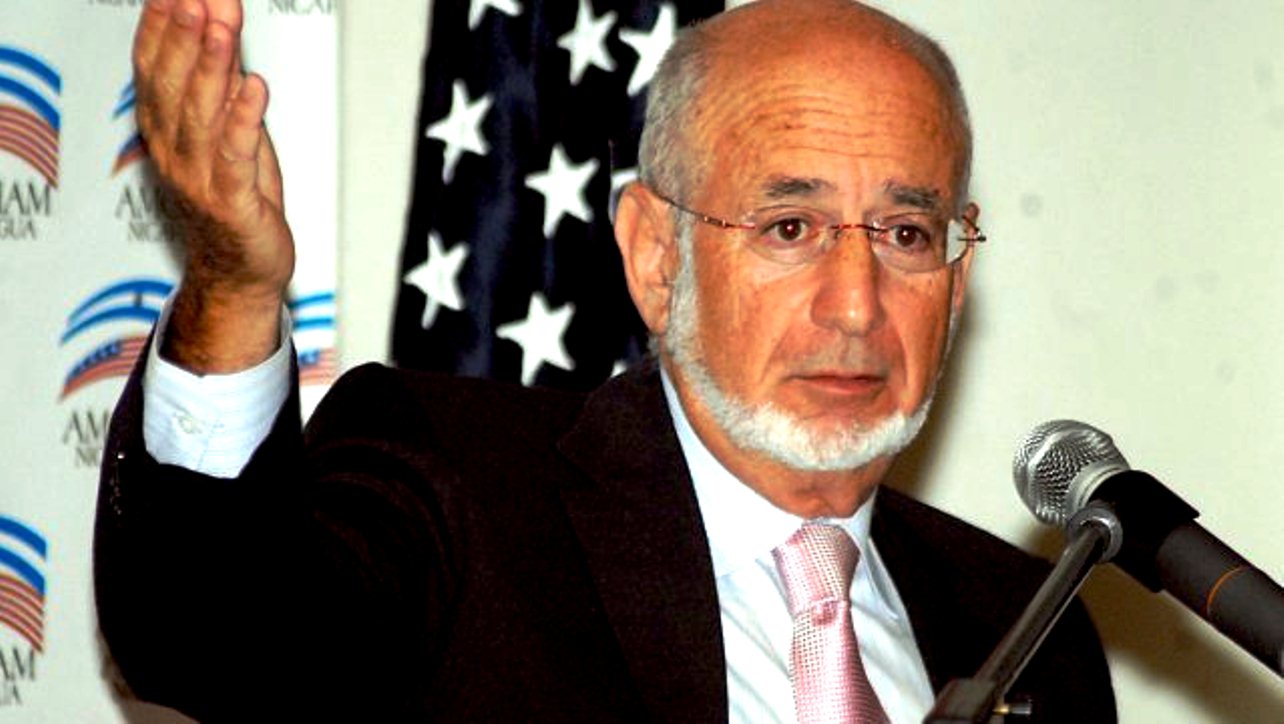

Richard E. Feinberg, Nonresident Senior Fellow – Foreign Policy, Latin America Initiative

Brookings, December 4, 2017

Original Article: Order from Chaos

In many ways, Raúl Castro’s 10-year presidential rule, ending in February 2018, has been utterly disappointing. Cuba’s economy is stagnant and economic reform has stalled. Political power remains highly centralized and secluded. The island’s educated youth are fleeing in droves for better opportunities abroad. And the Trump administration is renewing U.S. hostility.

Nevertheless, during his decade in power Raúl Castro oversaw historic shifts in Cuban foreign and domestic policies. Raúl initiated some policy innovations, deepened and consolidated others, and merely watched while forces beyond his control drove other changes. Regardless, these changes have paved the way for the successor generation of leaders—if they dare—to push Cuba forward into the 21st century.

MORE FRIENDS

Fidel’s younger brother, now 86, can be especially pleased with his achievements in foreign affairs. Cuba had been a colony of Spain, a dominion of U.S. capital, a cog within the Soviet-dominated Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (COMECON) system. Now, for the first time in its 500-year history, Cuba has escaped the grip of a single world power.

Today, Cuban traders circumnavigate the globe, engaging both state-directed and free-market economies. The top trading 10 partners in goods in 2016 were (in rank order): China, Venezuela, Spain, Canada, Brazil, Mexico, Italy, Argentina, Germany, and Vietnam. The next tier of merchandise trading partners (between $275 million and $100 million) includes the United States, France, Algeria, the Netherlands, Russia, and Trinidad and Tobago. No single country accounts for more than 20 percent of total merchandise trade.

This trade diversification began in the 1990s following the collapse of the Soviet Union, but Raúl’s economic team extended and consolidated it. Under Raúl, Cuba also expanded the number of countries that purchase its main service export—the labor of educated professionals, especially in the medical field. While Fidel initiated large-scale service exports to Venezuela, Raúl followed suit with Brazil and dozens of other developing countries.

In the last 10 years, Cuba has also diversified the sources of foreign investment. For example, in the economy’s bright spot, international tourism, investors hail from Spain, France, Canada, Germany, Switzerland, Canada, China, and Malaysia, among other locations.

A small island economy cannot hope to be fully autonomous; it must adapt to global constraints. But by diversifying its economic partners, Cuba has minimized its vulnerability to external dictates, and maximized its own margin for maneuver. This diversification of economic partnerships has paid handsome diplomatic dividends. Cuba has become an accepted participant in various Latin American forums and diplomatic initiatives; overcame its exclusion from the Summit of the Americas leaders’ meetings; gained membership in the Central American Bank for Economic Integration (CABEI); and gained access to resources at the multilateral Andean Development Corporation (CAF). President Donald Trump is alone in his efforts to damage the Cuban economy through comprehensive economic sanctions.

BREAKING IDEOLOGICAL BARRIERS

The slow, halting pace of economic reform has discouraged many Cubans, especially recent university graduates. Conservative forces resisting change remain strong within the Cuban Communist Party. Nevertheless, Raúl leaves a legacy that could greatly facilitate the work of reformers in the future. (I will further evaluate the economic reforms and pathways forward in a February 2018 Brookings policy brief.)

Raúl’s legacy lies not in standard measures of economic performance, such as per capita GDP growth, labor productivity, or investment rates, where results have varied from disappointing to disastrous. Rather, Raúl’s legacy in economic policy lies in breaking once forbidding ideological barriers. True, Raúl’s public statements often have been contradictory and shifting, as he apparently sought to balance conflicting tendencies within the Cuban Communist Party. But in key areas, Raúl demolished or at least cracked these obstacles to change: rejection of globalization (a favorite Fidel bugaboo), fear of foreign investment, and hostility to private business and markets. He also transformed relations with the United States.

In daily life, Cubans have left behind the comfort of social uniformity and relative economic equality for the more tumultuous worlds of greater social heterogeneity and income inequalities.

Raúl is no cheerleader for globalization. But he set aside his brother’s heated denunciations of multinational corporations and “exploitative” markets. Instead, he went about the practical business of building economic relations with a multitude of governments and foreign corporations. Without much pomp and circumstance (although there was the occasional ribbon-cutting), Raúl advanced the process of normalizing Cuba’s integration into global markets.

Raúl’s decision to normalize diplomatic relations with “the historic enemy,” the United States, dramatically revised his regime’s foreign policy doctrine. The hegemon just across the Florida Straits was no longer an imminent, existential threat, readily justifying economic deprivations and tight political restrictions. Notwithstanding the altered attitude in Washington today, so far a number of the concrete gains from the Obama era détente remain in place, notably the facilitation of travel (commercial airline flights and cruise ships) and the generous flows of remittances to many Cuban families, whether for household consumption or business start-ups.

Of the reforms most directly attributable to Raúl, the suppression of the special (and expensive) permit to travel abroad was among the most important to many Cubans. As a result, most Cubans can freely leave the island (provided they can acquire an entry visa elsewhere), to be enriched by their contact with foreign lands and ideas. Greater access to mobile technology and rapidly expanding social media, permission to sell homes and cars, and more freedom to stay in once-forbidden tourist hotels have also improved life for many Cubans during his tenure.

De facto, by building commercial partnerships worldwide, and by accepting the freedom to travel, Cuba has now embraced core components of globalization.

OPENING TO FOREIGN INVESTMENT

To stave off complete economic collapse in the early 1990s, Fidel had invited in limited foreign investment. El Comandante en Jefe made these concessions holding his sensitive ideological nose and again closed Cuba’s borders once he felt politically secure. In sharp contrast, Raúl has publicly chastised his ministers for not accelerating foreign capital inflows (although he hesitated to fire them).

Periodically, the government releases a “Portfolio of Opportunities for Foreign Investment.” Each edition is fatter and glossier; the 300-page 2017-2018 version features 456 projects with a cumulative price tag of $11 billion. Yes, most projects have remained on paper, victims of bureaucratic foot-dragging and red tape; but these documents are products of an inter-agency process whereby many ministries and state enterprises join in a collective waving of hands to the international commercial community.

In a 2011 official document outlining proposed reforms, foreign investment was derided as “complementary,” a secondary afterthought. In contrast, when addressing Havana’s annual international trade fair in 2017, Raúl’s minister for foreign trade and investment sang a very different tune: “Today foreign investment ceases to be a complement and has become an essential issue for the country.”

Mariel, the new economic development zone facing the Straits of Florida, has gotten off to a slow start, having approved over three years only 26 projects worth about $1 billion. However, 15 of these projects have broken through another ideological barrier: allowing 100 percent foreign ownership.

LEGITIMIZING PRIVATE PROPERTY

Fidel disliked and distrusted private property. In 1968, for example, he nationalized remaining mom-and-pop businesses. In contrast, over the last decade the government has issued hundreds of thousands of licenses to small-scale private businesses. Raúl has also encouraged some 200,000 Cuban families to farm as homesteaders (although not all survived). In addition to these authorized private businesses, many Cubans augment their income in more-or-less tolerated gray-market activities. Altogether, as much as 40 percent of the Cuban workforce have at least one foot in the private sector.

Recently, Raúl criticized private business for illicit activities, and the government halted the granting of new business licenses. Nevertheless, these concessions to anxious Communist Party stalwarts appear to be a temporary pause. The ideological foundations, and public constituency, for the acceptance and eventual expansion of a market-driven private sector have most likely been set too deep for a full-blown counter-revolution to succeed.

SOCIAL RELAXATION

This increase in economic pluralism has unleashed public debates on economic policy. Criticism of government performance is widely voiced with less fear, even if journalists and academics are still careful not to directly confront senior authority.

Another major shift that accelerated during the last decade: the evolution of Cuban society from socialist uniformity toward a more heterogeneous mix of property relations, income levels, and social styles. While legal statutes remain to be written, property can now be private (often in partnership with diaspora capital), cooperative (in numerous variations) and foreign-owned, as well as state controlled.

Income inequalities have become more visible, even if less jarring than in other Latin American and Caribbean nations. Many Cubans still honor social solidarity. But the transition toward a more normal, relaxed, and individualistic society is unmistakable. On Havana’s streets, Cuban youth—increasingly exposed to international tourists, travel opportunities and the worldwide web—sport the variety of hairstyles, tattoos, music, and other signatures of global youth.

These ideological adaptations do not guarantee speedy policy changes, much less their faithful implementation. The Cuban government is grappling with a severe foreign exchange crisis, and the sudden, unanticipated chill in bilateral relations imposed by the United States. All the more reasons for the next generation of Cuban leaders to build upon the diversity of international economic associations and the new ideological currents unleashed during the reign of the second and last Castro brother—and to launch their island state into deeper phases of global integration and economic transformation.

Richard Feinberg

Richard Feinberg