After half a century under Fidel, Cubans feel a wary sense of possibility. But this time, don’t expect a revolution.

By Cynthia Gorney

Original Article here: Cuba’s New Now

Photo Gallery for Article: Cuba Photos

Onions for Sale, Spring 2010

“I want to show you where we’re hiding it,” Eduardo said.

Bad idea, I said. Someone will notice the foreigner and wreck the plan.

“No, I figured it out,” Eduardo said. “You won’t get out of the car. I’ll drive by, slowly, not so slow that we attract attention. I’ll tell you when to look. Be discreet.”

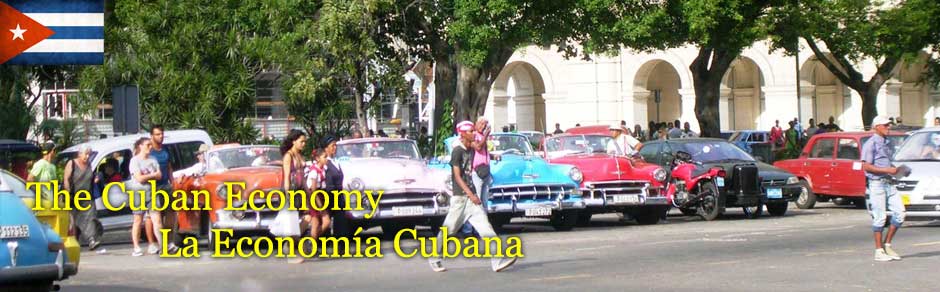

He had borrowed a friend’s máquina, which means “machine” but is also what Cubans call the old American cars that are ubiquitous in the Havana souvenir postcards. This one was a 1956 Plymouth of a lurid color that I teased him about, but I pulled the passenger door shut gently, the way Cubans always remind you to, out of respect for their máquinas’ advanced age. Now we were driving along the coast, some distance from Havana, into the coastal town where Eduardo and nine other men had paid a guy, in secret, to build a boat sturdy enough to motor them all out of Cuba at once.

“There,” Eduardo said, and slowed the Plymouth. Between two peeling-paint buildings, on the inland side of the street, a narrow alley ended in a windowless structure the size of a one-car garage. “We’ll have to carry it out and wheel it up the alley,” he said. “Then it’s a whole block along this main street, toward that gravel that leads into the water. We’ll wait until after midnight. But navy helicopters patrol offshore.”

He peered into his rearview mirror at the empty street behind him, concentrating, so I shut up. Eduardo is 35, a light-skinned Cuban with short brown hair and a wrestler’s build, and in the months since we first met last winter—he’s a former construction worker but that day was driving a borrowed Korean sedan and trying to earn money as an off-the-books cabdriver—we had taken to yelling good-naturedly and interrupting each other as we drove around La Habana Province, arguing about the New Changing Cuba. He said there was no such thing. I said people insisted there was. I invoked the many reports I was reading, with names like “Change in Post-Fidel Cuba” and “Cuba’s New Resolve.” Eduardo would gaze heavenward in exasperation. I invoked the much vaunted new rules opening up the controlled economy of socialist Cuba—the laws allowing people to buy and sell houses and cars openly, obtain bank loans, and work legally for themselves in a variety of small businesses rather than being obliged to work for the state.

But no. More eye rolling. “All that is for the benefit of these guys,” Eduardo said to me once, and tapped his own shoulder, the discreet Cuban signal for a person with military hardware and inner-circle political pull.

What about Fidel Castro having permanently left the presidency four years ago, formally yielding the office of commander in chief to his more flexible and pragmatic younger brother, Raúl?

“Viva Cuba Libre,” Eduardo muttered, mimicking a revolutionary exhortation we’d seen emblazoned high on an outdoor wall. Long live free Cuba. “Free from both of them,” he said. “That’s when there might be real change.”

Cuba, New Now, National Geographic

Private Parking Agent for City Parking Authorty