Yvon Grenier

Original Article from Literal: Reflections, Art and Culture: Pensamiento, Arte y Cultura here: Not Free But Comfy: Cuban Art Between State and Market

Successful artists (painters, sculptors, and performers) are part of the wealthiest 1 percent of the population in Cuba. For two decades, they have been able to sell their works abroad, even to Americans (art is not covered by the US embargo). Cuban art is mostly for export and it is a lucrative business. Artists who play by the rules have been able to leave and return to their country, on their own, for two decades. Ordinary Cubans were only granted this basic universal right (see Art.13 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights) last January, and “exiled” Cubans are still denied the right to return to the island.

In art, as in other forms of expression, everything is permitted in revolutionary Cuba. Except when it is not. As Fidel Castro proclaimed in 1961, in a famous speech to intellectuals, “Within the revolution, everything; against the revolution, nothing.” The Constitution stipulates: “Artistic creation is free, as long as its content is not contrary to the Revolution. The forms of expression in the arts are free.” Form and content are hard to dissociate in the visual arts. So, who is to make the call on “form” and “content,” and who figures out what is acceptably “within” La Revolución and what is not? Answer: La Revolución herself, that is to say, en dernière instance, Fidel and his brother Raúl.

Since 1959 the ambitious goal of the new regime in Cuba has been to create “a new man in a new society.” Official documents talk about La Revolución as “the most important cultural fact of our history.” By and large, in this “new society” the range of what can be expressed has been reduced, which has hurt creativity, but the array of cultural activities accessible to the population in general has expanded in many areas, namely in music, visual arts and performing arts. The Instituto Superior de Arte (ISA-1976), for instance, produced many very well trained artists, who went on to have successful national and international careers. It is the only graduate school solely for the arts in Latin America. Many, perhaps most of the ISA’s graduates now live in exile.

The visual arts are mostly for the happy few and they are typically less ideationally explicit in their “content” than other artistic or cultural forms. Consequently, in Cuba as in many other non-democratic countries, the government can cut visual artists a little slack. Visual artists have more “space” for expression than, say, writers or popular singers, who in turn enjoy a bit more leeway than academics. Nobody is less free than a journalist in Cuba. In other words, Cubans are all equal, in being denied their “right to freedom of opinion and expression” (Art.19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights), but some are more equal than others.

New Cuban Art

Visual artists who have been working within institutional channels have tested the borders of the permissible more often than most other actors in the cultural field. The trend really started during the 1980s, when young painters such as Flavio Garciandia, Tomás Sánchez, José Manuel Fors, José Bedia, Gustavo Pérez, Ricardo Rodríguez, Leandro Soto, Israel León, Juan Francisco Elso, and Rubén Torres challenged the dominant revolutionary didacticism of the previous decade. They were not unlike the painters of the Generación de la ruptura in Mexico (Alberto Gironella, Vicente Rojo, José Luis Cuevas, Vlady, Pedro Coronel), who defied their own dominant ‘socialist realist’ tradition (Mexican muralism) during the 1950s.

The exposition Volumen Uno in January of 1981 in Havana officially inaugurated the so-called “New Cuban Art.” For painter Flavio Garciandia: “When we did Volumen Uno we were very, very conscious of the fact that the ‘state of the arts’ in Cuba was just awful, precisely because of those ideas of programmatic contentism [contenidismo programático]. We knew that Volumen Uno was a political exhibition… very polemical, precisely because we were positioning the problems in another part, not in the ‘content’–we had a completely distinct focus and in that moment this was practically a political challenge. . . Given the circumstances of the context, it was an exhibition that was proposing… art as a totally autonomous activity, not as a weapon of the Revolution as the Constitution says.” This (relative) “autonomy” opened up new artistic possibilities. Arguably, it made it easier for artists to eschew controversial issues or events, such as the tragedy that took place only eight months earlier: the 1980 Mariel boatlift, in which 125,000 people left the country (among them many artists and intellectuals). No reference to this exodus (and the shameful actos de repudio that accompanied it) is made in Volumen Uno.

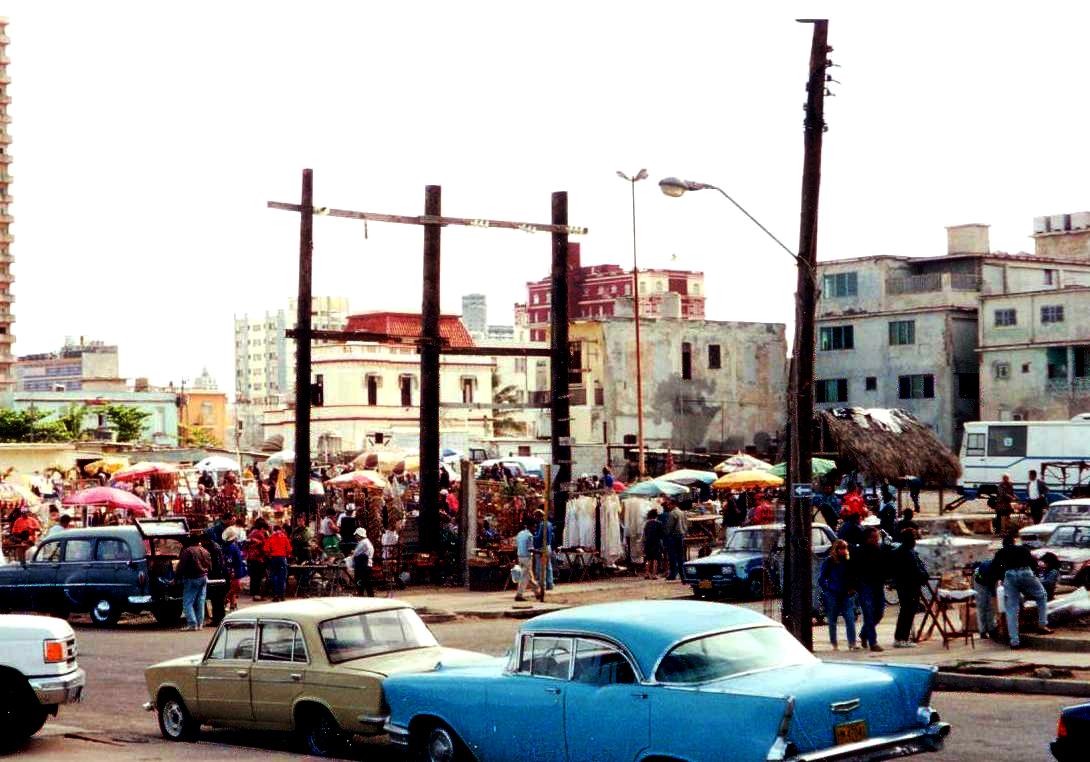

The emergence of the New Cuban Art coincided with the twilight of the Cold War and the deepening of globalization in the field of art. The Soviet Union (and its annual four billion dollars-a-year subsidy to Cuba) came to an abrupt end and Cuba was forced to open up to market forces. Meanwhile, in the art world, the Post Cold War era saw the début of numerous new Biennials, far away from the traditional capitals of global art: i.e. Sharjah, UAE (1993), Shanghai (1996), Mercosur (Brazil, 1997), Dak’art (1998) and Busan (Korea 1998). The first Havana Biennial (1984) can be seen as an early manifestation of this trend, in addition to being the only one operated by a socialist country. In the new global market for art, the purported anti-imperialist and anti-consumerist mission of the Havana Biennial offered a refreshing choice for multicultural or postcolonial curators and critics, and a thrilling one for decadently rich consumers. For instance, in 1990 the German chocolate magnate and art collector Peter Ludwig acquired more than two thirds of the exhibition of contemporary Cuban art ‘Kuba OK,’ in addition to many other famous works of the artists of the 1990s generation.

Art and the new Gatekeeper State

Art and the new Gatekeeper State

The 1980s generation (especially during the second half of the decade) was arguably more audacious and politically driven than the subsequent ones. But most prominent members of this generation left the country at the end of the 1980s and early 1990s. The artists who stayed in the country found a comfort zone, negotiating the terms of their subordination with what political scientist Javier Corrales calls the new “gatekeeper” state: e.g. a state that “decide[s] who can benefit from market activities and by how much.” Thus, the cultural field offered a testing ground for the kind of “segmented marketization” and limited liberalization of subsequent years, when brother Raúl inherited the presidency.

Artists quickly learned to deal with the international market, giving it what it wants: Cubanía products, with muted and aestheticized political overtones that make both the artist and the viewer feel astute, all of which transacted with the global language of art of the time (mainly conceptual art and arte povera). For all the talk about postmodern art in Cuba, the country is literally stuck in modernity, with primary concerns about national identity, sovereignty, material well-being, basic freedom and security. These modern concerns are omnipresent in New Cuban art, where they are at once localized and transcended by postmodern aesthetics. This confers New Cuban Art a trendy “glocal” cachet that simultaneously insinuates and defuses “content.”

Cuban artists are masters of double entendre and detachment (parody, irony, sarcasm, and pastiche). They know what the taboos are: play with the chain but not with the monkey; don’t challenge La Revolución and its metonymic association with the Castro brothers. (About Fidel: according to Andrés Oppenheimer, in the early 1990s the guidelines were revised: “it was forbidden to show him standing next to anybody taller or to show him eating, and it was forbidden to divulge any information on his personal life.”) Yet, the global market likes its Cuban art with a dash of political irreverence. The regime can afford to appear open-minded since it is largely inconsequential on the island.

Even though artists are pretty shrewd when guessing the “parameters,” it is still perilous to “play with the chain.” Expositions have been censored and cancelled; artists are reprimanded and sometimes jailed. The performance artist Angel Delgado got six months in jail for publicly defecating on a copy of the daily Granma, during the exhibition “El objeto esculturado” (1989). According to Luis Camnitzer, the exhibition at the Castillo de La Real Fuerza in February of 1989 was closed “when it was found to include a portrait of Fidel Castro in drag with large breasts and leading a political rally, and Marcia Leiseca, the vice minister of culture, was relocated to the Casa de las Américas.” Artists have been castigated for speaking their mind on the public issues (most recently, for instance, the painter and sculptor Pedro Pablo Oliva lost his studio and his seat in the provincial assembly). Admittedly, it is not simple for outsiders (such as this author) to fully appreciate the day-to-day courage of individuals who strive to work and live under very difficult circumstances in the country of their choice: their own.

Continue reading: Not Free But Comfy