“Quartz Obsession”

March 16, 2018 at 3:46:38 PM

Cuba has one of the lowest rates of internet usage in the Western Hemisphere, and access to media is strictly restricted—but that doesn’t stop Cubans from watching Game of Thrones. Their secret is El Paquete Semanal (“The Weekly Packet”), a clandestine in-person file-sharing network that distributes hard drives and flash drives full of media.

Nobody quite knows how El Paquete, which has thrived since the mid-2000s, is created or how it makes its way across the country every week. But Cubans have come to rely on the pervasive distribution of music, TV, and movies—not to mention pirated software and e-commerce platforms.

Ultimately, the uniquely Cuban tech phenomenon is proof that just like life in Jurassic Park, information always finds a way—especially when you’re jonesing for the latest episode of a subtitled South Korean soap opera and the closest open internet is an ocean away.

BY THE DIGITS

- 5.6%: Cuban households with dial-up connections, at speeds of 4–5 kB/s

- 386%: Cost of household internet service in Cuba as a percentage of per capita GDP

- 0.007%: Cuban broadband internet penetration (8,157 connections for 11 million people)

- 2018: Year the Cuban government has promised to offer mobile internet service

- $2: Cost per hour of public Wi-Fi hotspot access, equivalent to 10% of the average monthly salary

- $3: Estimated cost of one week’s Paquete, accessed on a Monday

- $1: Estimated cost on a Wednesday

How does it work?

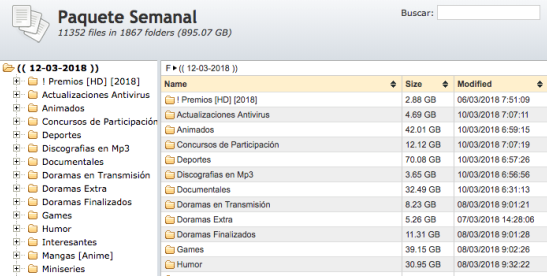

There are a lot of question marks about El Paquete—more accurately, Los Paquetes, as there are reportedly several versions—but this much is clear: At the end of each week, its creator(s) compile the most in-demand media of the week—roughly 15,000 to 180,000 files, 1 terabyte in total. The provenance is murky, but the most likely source is a mix of illicit broadband internet access, secret satellite dishes, and hard drives and flash drives smuggled in from overseas.

From there, it’s top-down distribution. A network of Paquete wholesalers (many based in street-level phone repair and DVD shops) copy the contents onto their own hard drives and flash drives, which are then copied many more times. The last links are the door-to-door Paquete delivery guys, who will bring it to individual residences, copying over select files or the entire thing to customers.

The network is based in the capital Havana, but El Paquete also makes its way to most Cuban towns, with a noticeable time lag. El Paquete is most expensive early in the week; by Thursday or so, prices will have dropped by 50% or more.

The kingpins of El Paquete

Former engineering student Elio Hector Lopez is one of the people credited with starting El Paquete around 2006, where it built on longstanding clandestine networks used to distribute physical media like books, videotapes, CDs, and DVDs.

“At the beginning we saw this as a way to make money—but after having penetrated the entire country we see it more as a responsibility,” he told NBC in 2015.

“For the time being, El Paquete replaces the Internet for those who don’t have it,” Lopez told Reuters. “If tomorrow El Paquete disappears I don’t know what people would do, it’s like water, or a pill for the Cuban body.” According to the CBC, as of 2016 Lopez had moved to the United States.

“El Paquete was founded by several people, each with a desire to find a way to entertain their towns,” he told Polygon last year. “We wanted to find a way for the island to see the world in ways outside of politics, showing them culture, sports, entertainment, economy and society, showing them all the things going on in the world that weren’t making it to our TVs.”

Cuba’s make-do culture

El Paquete is a distinct phenomenon of the internet age, but according to Nick Parish, author of a fascinating in-depth study,there’s an interesting precedent in Cuban history. After the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1989 left Cuba reeling, “the military issued a book called “Con Nuestros Propios Esfuerzos” (With Our Own Efforts) that served as a chronicle to survival through shared knowhow, with everything from horticultural knowledge and recipes to herbal medicines to public health to transport, featuring tips submitted by ordinary Cubans.”

This week’s list

A volunteer site, Paquete de Cuba, lists the weekly contents, though they’re not available for download.

In the absence of actual internet access, techies in Havana and elsewhere have created a homebrewed network called SNET “that reproduces much of the consumer internet we know in the free world,” according to Wired. It includes copycat versions of Facebook and Instagram—and facilitates dissemination of El Paquete.

How does advertising work?

There are classifieds in El Paquete. According to a report from the Yugoslavia-based Share Foundation: “If you send an SMS to a certain number, the content of the message will appear in the El Paquete folder ‘classifieds’ in form of a jpeg image that has your message on one half and some advertisement on the other half.”

But local ads are also embedded directly into the content: Users might also see video advertisements for local services embedded at the end of a trailer for a Hollywood movie, or ads sandwiched between magazine pages.

There’s even an e-commerce supplement: “a 199-page PDF catalog with interlinked product pages and ordering instructions, so people can purchase handmade products such as purses, shoes, boots, backpacks, and belts,” according to Nick Parish.

So, does the government know?

Cuba’s authoritarian government is known for its censorship and intolerance of dissent, which has prompted many conspiracy theories about El Paquete: Is it all a government scheme to placate the masses with the opiate-like effects of western mass media?

There’s perhaps one telltale clue that Raul Castro’s government chooses to tolerate the existence of El Paquete: It contains no porn or political speech, or even western news accounts that might run afoul of the country’s communist party.

“There exists a kind of established agreement in which El Paquete must not reproduce content critical of the government, propaganda, or pornography, and in exchange the state turns a blind eye,” one Paquete distributor told Cubanet.

At least, that was true until recently: Cubanet reports a new folder called “Tremendo lío” (“tremendous mess”) recently appeared in El Paquete, which contains videos from some Cuban social media stars who voice anti-government views, along with those who support it. Is this a brave new era for El Paquete, or a signal that a government crackdown is coming?

“In a country where materials, shopping, and consumption are limited to food and maybe clothing, El Paquete becomes a luxury, a form of asserting one’s independence from the state’s attempts to suppress individuality.”

— “El Paquete: A qualitative study of Cuba’s Transition from Socialism to Quasi-Capitalism,” an undergraduate thesis by Princeton sociology major Dennisse Calle.

“Prefiero gastar un dólar que estar como un zombi. (I would rather spend a dollar than be a zombie.)”

— El Paquete customer Alejandro Batista