By Richard Feinberg

Cuba Standard, May 7, 2014

Original Here: Cuba Standard

Among investors focused on Cuban markets, private bars and clubs are the new big thing. Within the last 18 months, enterprising Cuban investors have spiced up an already vibrating Havana night life by opening a variety of chic watering holes.

By all accounts, many investors are achieving their primary goal: rapid returns on risk capital.

And middle-class Cubans — not just tourists and expats — are enjoying the widening diversity of options for evening destinations.

Stiff competition, narrow market

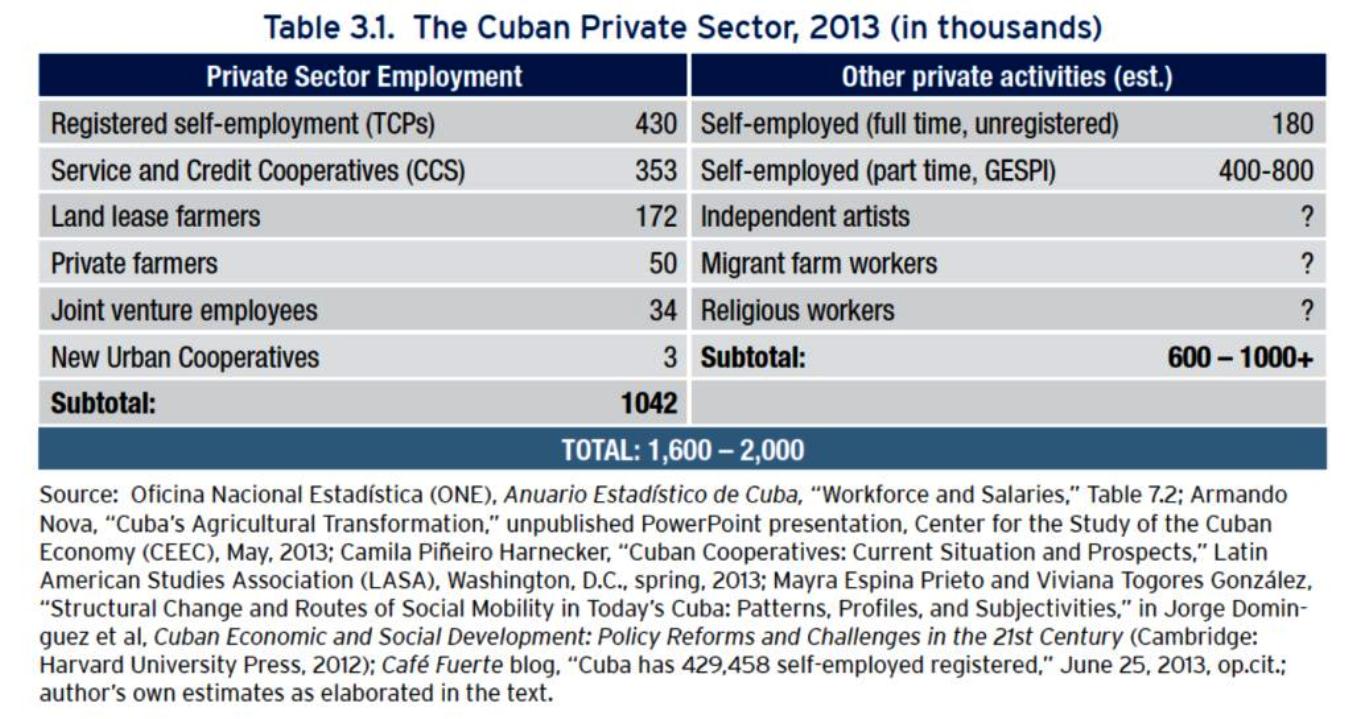

For the emerging private sector — promoted by Raúl Castro since he took over from his ailing brother Fidel in 2008 — the previous big story was the paladares, privately run restaurants generally located within family homes. But so many enterprising Cubans seized the opportunity to earn gastronomic profits that the restaurant market quickly turned terribly competitive.

Many fine-dining paladares cater primarily to well-heeled tourists, charging prices that are moderate by international standards but far out of the reach of nearly all Cubans. Most Cubans working for the state receive the miserable wage of $20 per month — roughly the cost of a single paladar meal.

Facing this dual challenge of stiff competition in the restaurant space and the narrow tourism market, innovative Cuban entrepreneurs seized upon nocturnal entertainment as an exciting solution. Havana is not without bars, often featuring Buena Vista Social Club–style bands in Havana Vieja that appeal to middle-age tourists — but not to hip young Cubans or international travelers looking for the latest music video or mixed cocktail creations.

The newly launched bars/clubs feature flat-screen TVs with contemporary sounds. Dancing begins around 10 pm and whirls well into the early morning hours. Some of the bar-hopping crowd may be exiting the paladares, in search of the after-hours fun for which Havana is so famous — but with a contemporary beat.

Significantly, the new upscale bars are also attracting Cubans – by keeping their prices within the range of what could be labeled the Cuban middle or upper-middle classes.

Entrance or cover charges are minimal and local beers sell for the equivalent of $2, tapas for just $2 – $6, heavier fare for $6 -15. These prices still lock out most Cubans, but are within the range of perhaps five percent of the 2 million Habaneros. (Alas, the Cuban government does not publish statistics on income distribution.)

Even if a Cuban couple limits their consumption to two beers each and a few snacks, how can they afford an evening on the town? Where do they find the $20 — the equivalent of a full month’s state salary? The sources of this middle-class purchasing power: profits from their own thriving private businesses, wages and tips earned in the tourist trade, bonuses granted by joint ventures, or remittances sent by generous family and friends living abroad. Cubans who served overseas — as diplomats, military attachés, or medical personnel — can accumulate savings. And privileged offspring of senior government officials are known to enjoy free beverages and bites.

As recently noted by AP correspondent Peter Orsi, the elites of the remarkably large and talented Cuban creative class — painters, dancers, musicians, film makers — also earn a good living; the farándula — the inbreed creative classes — congregate at Café Madrigal, Privé, and Espacios.

In Havana these days, trendy bars are not the only visible indicators of Cuba’s prosperous upper-middle classes and their lucky, beautiful children. Expensive daycare centers and domestic housekeepers, 21st century cars with private license plates replacing the iconic but decrepit 1950s Chevrolets, and expensive cell phones with e-mail service — all signal the emergence of new money.

At the new nocturnal watering holes, successful Cubans mingle comfortably with foreigners: the resident expatriate community of diplomats and business executives as well as tourists — mostly Europeans and Canadians, but also increasingly Americans, permitted to travel legally to Cuba under people-to-people educational programs licensed by the Obama administration.

The places

Two of the hottest Havana bars, Sangri-La and Up-and-Down (their ownership overlaps), are so packed on weekends that their overcrowded dance floors challenge even the most fluid salsa dancers. Intimate but very lively, Up-and-Down exploits the increasing stratification of Cuban society by differentiating the entry fee for the upstairs VIP lounges: a minimum of $20 consumption per person, priced for foreigners and a thin slice of the best-heeled Cubans. The bartender at Up-and-Down is rightly famous for his designer tropical drinks laced with plentiful pours.

A combination restaurant and terraza bar, El Cocinero is a dramatic conversion of an old cooking oil factory into a two-floor industrial entertainment space. The plush first floor dining décor is dominated by a large black-and-white minimalist painting, while the al fresco upstairs features comfortable butterfly lounge chairs and a neon-lite bar. Typically, the denim-clad waitresses are youthful and attractive, and frequently with university degrees in their back pockets.

Product placement

A theatrical production of a Cuban-authored drama currently running in Havana, Rascacielos (Skyscrapers), is co-sponsored by the embassies of Spain and The Netherlands — and by El Cocinero and StarBien, a plush paladar (co-owned and managed by the gracious son of the minister of the interior). The commercial sponsorships earned product placements — explicit mentions in the text of the play — one dramatic signal of the growing weight and self-confidence of the emerging private sector.

Other trendy Havana dispensaries of alcohol and nocturnal diversion include Fábrica de Arte (featuring avantgarde paintings), Capricho (tasty tapas, serene ambiance), Escencia Havana (pre-revolution nostalgia in an 1880 villa), O’Reilly 304 (in Old Havana, superb vegetarian soup with three varieties of chili peppers), Toke (a mostly gay clientele, next to the Cabaret Las Vegas), and two new dimly lit dance clubs catering to a younger crowd, Melén and Las Piedras.

El Cocinero upstairs; Photos by Richard Feinberg

El Cocinero upstairs; Photos by Richard Feinberg

In many of Havana’s new bars, the décor and the crowd are sophisticated and universal: Their Miami equivalents have similar vibes, albeit with more bling and, as one Cuban male observed, more silicon. Island-bound Cubans have less jewelry to flaunt, and may sense that the Communist government, while more permissive today than during the decades of Fidel Castro’s austere rule, would still look askance at ostentatious displays of new wealth.

Small investment, quick return

Chats with owners and managers of these after-hour establishments suggest initial capital investments of roughly $30,000 – $70,000 (small by international standards). No entrepreneur reported commercial bank backing, which is scarce in Cuba. Rather, funds come from savings of family and friends, and in some cases money transfers from abroad – as donations, loans, or informal equity arrangements. Working within an uncertain business climate, these newly minted Cuban entrepreneurs often seek to recoup their capital in 12-24 months, a potentially feasible goal due to low costs of labor, rent, and utilities, and often interest-free financing.

Paul Sosa at his bar

Paul Sosa at his bar

The award for the most economical opening goes to Mamainé (as in the popular Cuban song, Mamainé, Mamainé, todos los negros tomamos café), a comfortable coffee and cocktail bar constructed by environmentalist and artist Paul Sosa using recycled woods and iron work. Spending less than $5,000 to fashion the 36-seat establishment within his parents’ home, Paul attracts both tourists and locals with strong $1 espresso coffees and $2 made-to-order mojitos.

State-owned beer garden

Not to be outdone by the dynamic private sector, Cuban state companies have recently opened two large bars. Sloppy Joe’s, a revival of a pre-revolutionary saloon with a legendary 59-foot mahogany bar, once again caters mostly to tourists. More original, the government gloriously transformed an old timber and tobacco warehouse on Havana Bay into a large beer garden. The affordable prices and spectacular brightly painted murals attract Cuban families as well as foreigners. On one Sunday afternoon, the author viewed more than one Cuban child watching his parents enjoy the Austrian-made tall tubes of chilled beer.

Old warehouse, new beer garden

Old warehouse, new beer garden

Cuban capitalists not only must confront uneven competition from state-run firms, but also face regulatory uncertainty: bars are still not an officially sanctioned category of business, so their owners must register them as restaurants — making them vulnerable to government inspectors. Not surprisingly, in this high-risk business climate, investors seek a quick return on capital. But short of an abrupt shift in government policy, it is a safe bet that bold entrepreneurs will continue to provide Havana’s after-hours revelers with new and exciting entertainment options.

Richard E. Feinberg, professor of international economy at the University of California, San Diego, writes about and travels frequently to Cuba. Three of his recent publications on the Cuban economy, including Safe Landing for Cuba?, can be found at www.brookings.edu