World Affairs Journal September/October Issue, 2015.

World Affairs Journal September/October Issue, 2015.

José Azel

Eight hundred years ago, the Magna Carta laid the foundations for individual freedoms, the rule of law and for limits on the absolute power of the ruler.

King John of England, who signed this great document, believed that since he governed by divine right, there were no limits on his authority. But his need for money outweighed this principle and he acceded to his barons’ demand to sign the document limiting his powers, in exchange for their help.

King John then appealed to Pope Innocent III who promptly declared the Magna Carta to be “not only shameful and demeaning but also illegal and unjust” and deemed the charter to be “null and void of all validity forever.” Thus from the beginning of the conflict between individual rights and unlimited authority, the Church sided with authority. It is a position that, with notable exceptions has, and continues to characterize the conduct of Church-State affairs.

In 1929, the Holy See signed with Benito Mussolini’s Fascist government the Lateran Treaty which recognized the Vatican as an independent state. In exchange for the Pope’s public support, Mussolini also agreed to provide the Church with financial backing.

In 1933, the Vatican’s Secretary of State Eugenio Pacelli (later Pope Pius XII) signed on behalf of Pope Pius XI, the Reich Concordat to advance the rights of the Catholic Church in Germany. The treaty predictably gave moral legitimacy to the Nazi regime and constrained the political activism of the German Catholic clergy which had been critical of Nazism. Similarly, advancing the Church’s interests in Cuba is the explanation given for the Church’s hierarchy coziness with the Castro regime.

For most of us the Catholic Church is simply a religion, but the fact is that it is also a state with its own international politico-economic interests and views. It is hard to discern the defense of any moral or religious principles in the above historic undertakings of the Church-State.

These doings of the Church, as a state in partnership with authoritarian rule, are in sharp contrast with the Biblical rendition, where Christ was persecuted for his political views by a tyrannical regime acting in complicity with the leadership of His church. Cubans today are also politically persecuted by a tyrannical regime. The question arises as to whether the leadership of the Catholic Church will side with the people or with the Castro regime.

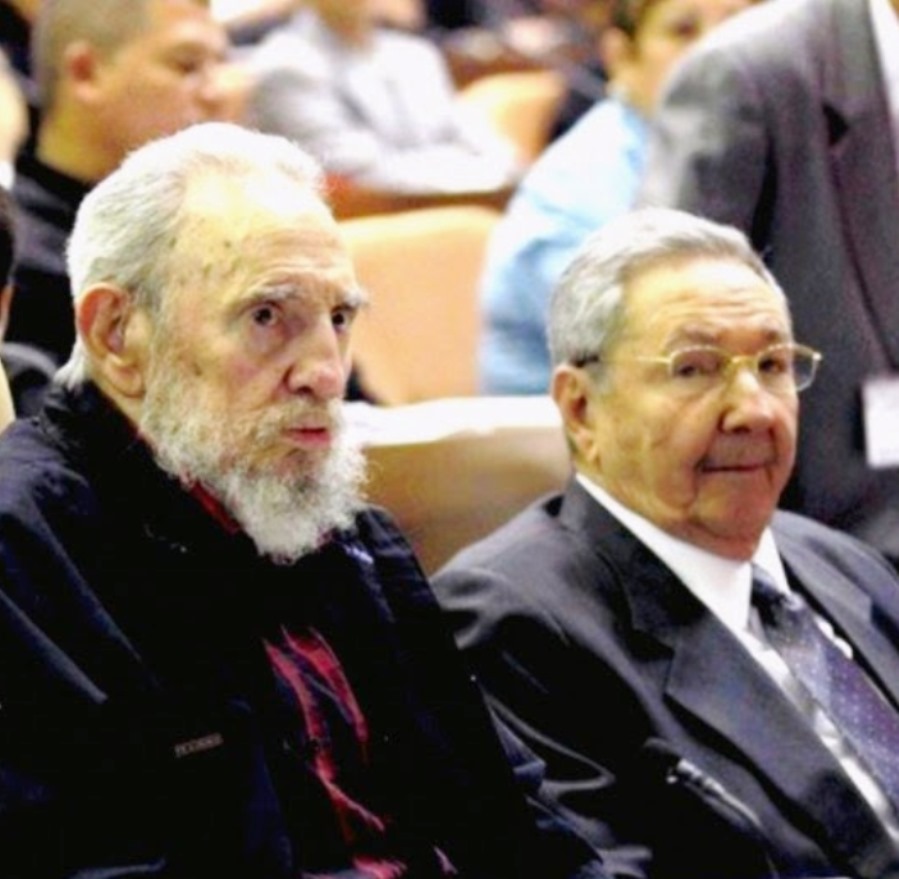

Pope Francis probably, was not thinking of Magna Carta, the Lateran Treaty or the Reich Concordat, when he warmly received General Raul Castro in the Vatican earlier this spring, and he probably won’t be thinking about that foundational document for individual freedoms, the rule of law and for limits on the absolute power of the ruler or how the medieval Church spurned it when he travels to Cuba in September. But the questions of the Vatican’s support for authoritarianism and the Pope’s political ideology will be in the background of his visit nonetheless.

In political terms, Pope Francis is himself the head of an authoritarian state -an oligarchical theocracy where only the aristocracy -the Princes of the College of Cardinals- participate in the selection of the ruler. Most religions do not follow a democratic structure, but the Catholic Church is unique in that it is also a state recognized by international law.

Pope Francis may seem to be sailing against the winds of this structure in some of his carefully publicized “iconoclasms,” but clues he has left as to his political and economic thought regarding Cuba show someone very comfortable with certain status quos.

In 1998, then Archbishop of Buenos Aires, Monsignor Jorge Mario Bergoglio, as the Pope was then known, authored a book titled: “Dialogues between John Paul II and Fidel Castro.” In my reading of the Pope’s complex Spanish prose, he favors socialism over capitalism provided it incorporates theism. He does not take issue with Fidel Castro’s claim that “Karl Marx’s doctrine is very close to the Sermon on the Mount,” and views the Cuban polity as in harmony with the Church’s social doctrine.

Following Church tradition he severely condemns U.S. economic sanctions, but Pope Francis goes much further. He uses Cuba’s inaccurate and politically charged term “blockade” and echoes the Cuban government’s allegations about its condign evil. He then criticizes free markets, noting that “neoliberal capitalism is a model that subordinates human beings and conditions development to pure market forces…thus humanity attends a cruel spectacle that crystalizes the enrichment of the few at the expense of the impoverishment of the many.” (Author’s translation)

In his prologue to “Dialogues between John Paul II and Fidel Castro,” Monsignor Bergoglio leaves no doubt that he sympathizes with the Cuban dictatorship and that he is not a fan of liberal democracy or free markets. He clearly believes in a very large, authoritarian role for the state in social and economic affairs. Perhaps, as many of his generation, the Pope’s understanding of economics and governance was perversely tainted by Argentina’s Peronist trajectory and the country’s continued corrupt mixture of statism and crony capitalism.

His language in the prologue is reminiscent of the “Liberation Theology” movement that developed in Latin America in the 1960’s and became very intertwined with Marxist ideology. Fathered by Peruvian priest Gustavo Gutierrez, the liberation theology movement provided the intellectual foundations that, with Cuban support, served to orchestrate “wars of national liberation” throughout the continent. Its iconography portrayed Jesus as a guerrilla with an AK 47 slung over his shoulder.

John Paul II and Benedict XVI censured Liberation Theology, but after Pope Francis met with father Gutierrez in 2013 in “a strictly private visit,” L’Osservatore Romano, the Vatican’s semi-official newspaper, published an essay stating that with the election of the first pope from Latin America Liberation Theology can no longer “remain in the shadows to which it has been relegated for some years…”

The political ideology of the Argentinian Monsignor Bergoglio may not have been of any transcendental significance. But as Pope Francis, he is now the head of a state with defined international political and economic interests. These state-interests and personal ideology will be in full display in his upcoming visit to Cuba and the United States.

In “Dialogues between John Paul II and Fidel Castro,” Pope Francis speaks of a “shared solidarity” but, as with Pope Innocent III’s rejection of the Magna Carta, that solidarity appears to be with the nondemocratic illegitimate authority in Cuba and not with the people. This is a tragic echo of the Cuban wars for independence when the Church sided with the Spanish Crown and not with the Cuban “mambises” fighting for freedom. No wonder that when Cuba gained its independence, many Cubans saw the Church as an enemy of the new nation.

In his September visit Pope Francis will have a chance to reverse this history and unequivocally put the Church on the side of the people, especially with the black and mulatto majority in the Island. If he does not, history will judge him as unkindly as it has Innocent III. When the Castros’ tropical gulag finally fades into the past, Cubans will remember that this Pope had a choice between freedom and authoritarianism, just as his predecessor did eight hundred years ago, and picked the wrong side.

José Azel is a Senior Scholar at the Institute for Cuban and Cuban-American Studies, University of Miami and the author of the book “Mañana in Cuba.”

Preface

Preface