ASCE Conference Proceedings, 2018

Complete Article: Cuban Demography

INTRODUCTION

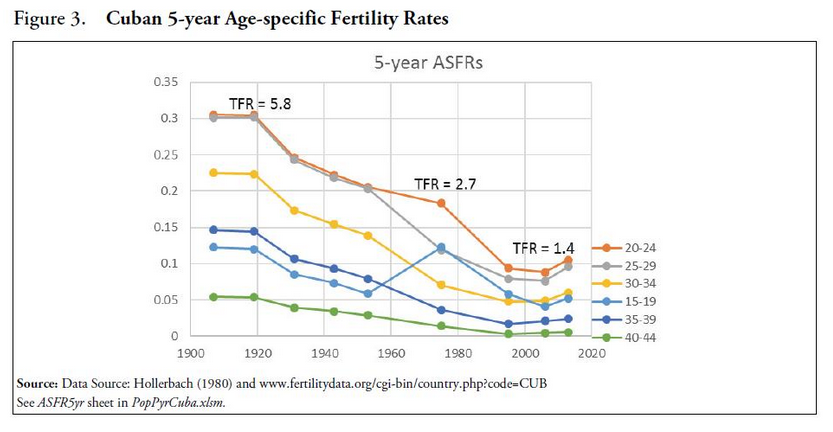

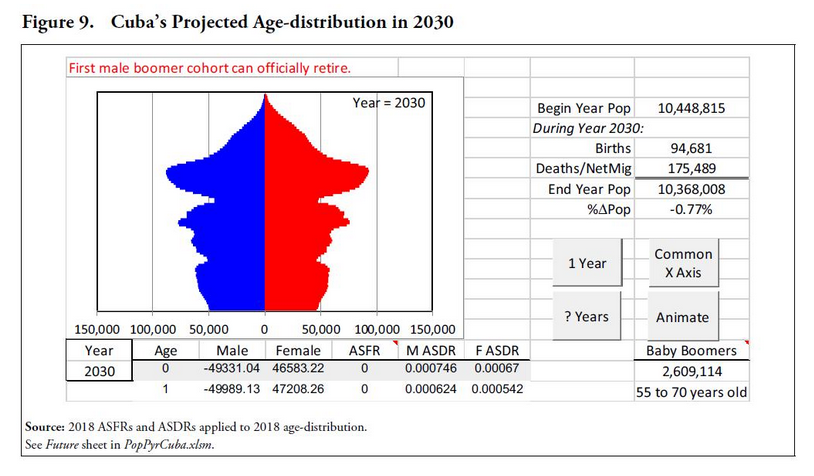

Cuba is facing a demographic storm that will stress its economy and society: its large baby boom generation is reaching retirement age and fertility is extremely low. While this is not an original observation (Hollerbach, 1980; Díaz-Briquets, 2015 and 2016), this paper uses single-year age-distribution data to show the seriousness of the situation. Unlike previous work (including that at the Cuban government’s Oficina Nacional de Estadística e Información (ONEI), www.one.cu), which focuses on total population change and other aggregates, this paper presents and analyzes the movement of the entire age-distribution over time. Thus, the data display methods adopted in this paper more dramatically show the demographic challenges facing Cuba.

The economic impact of an aging population is usually presented in terms of resources needed for health care and social services. The old age dependency ratio (the fraction of adults over 65 years old) conveys the idea that society must find a way to pay for care of the elderly. While important, this understates the effect of population aging and misses a mechanism through which it influences the economy. A much more serious challenge for an economy than taking care of the aged revolves around the attitudes and expectations of a society dominated by old people. The old are more pessimistic, conservative, and short-run oriented than the young.

While Keynes (1936, Ch 12:VII) highlighted animal spirits, “a spontaneous urge to action rather than inaction,” as a driver of fluctuations in a market economy, economists have little to say about the effect of expectations on long-run growth. Below are rudimentary thoughts on why a society dominated by the old might languish. The optimism of young people drives their energy and motivation to undertake a whole host of activities, including starting new businesses, trying new products, building new homes, and moving to new cities. The old, unlike the young, see the end of life and this affects their outlook. For many, the past seems better than the future and they stand pat—personally, socially, and economically.

Risk taking falls as people age and this occurs in every aspect of life. We settle into patterns and stick to what works. In terms of the economy, old people are less likely to buy new products and invest aggressively. They are more concerned with maintaining and conserving what they have than in taking chances with their accumulated wealth.

Young people provide a dynamism to the economy that is fundamental to the success of innovation and technological change. General outlook, attitudes toward risk-taking, and time horizon considerations are all highly correlated and change together as we age. Older people become more negative, careful, and unenthusiastic. These attitudes drag the economy. They have always been there, but they have never been as noticeable and prominent as they are today because of a worldwide revolution in demography.

Countries around the world face aging population distributions that will hamper economic performance. Rich countries, like Japan, are better able to withstand these demographic headwinds. Those that can attract immigrants, like the United States and Germany, can bolster diminishing numbers of younger aged cohorts by welcoming young people from other countries, although this solution is fraught with challenging political and social effects.

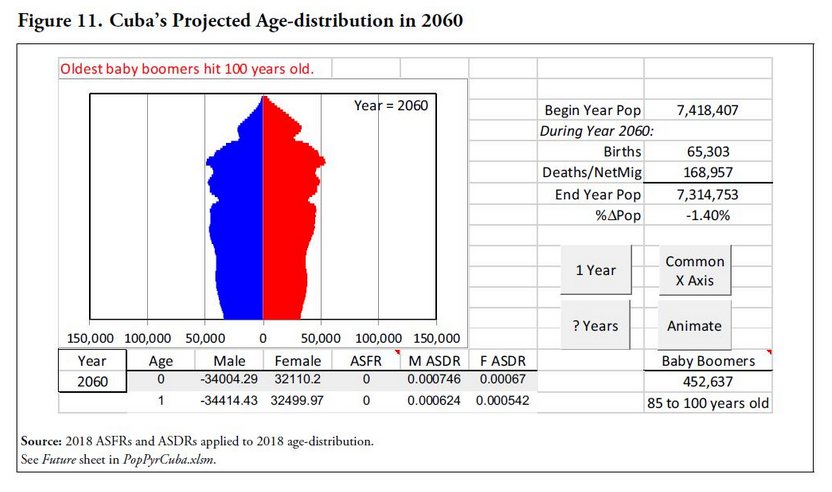

Cuba is in a particularly vulnerable position. Not only are the demographic forces exceptionally strong, but the economy is unusually weak. This paper will focus on the former, examining changes in the population age-distribution since the Revolution and forecasting future outcomes. Even if Cuba somehow manages to reform the economy and incorporate market-based incentives, its population age-distribution presents formidable challenges for an economic take-off. Again, this is not merely an issue of resources devoted to caring for the aged, but requires figuring out how to overcome the stagnation resulting from an economy dominated by old people. Without the energy, optimism, and risk-seeking of the young, the Cuban economy’s long-run future seems bleak.

The next section uses a macro-enabled Excel workbook, PopPyrCuba.xslm, to analyze Cuba’s recent demographic past and current situation. Age-specific fertility and death rates are then used to examine future prospects by iteration.

Continue Reading: Cuban Demography

*

*

*

*

CONCLUSION

Although the demographic challenge facing Cuba and its low fertility have been known for years, the primary contribution of this paper lies in the presentation of the data through the macro-enabled Excel workbook, PopPyrCuba.xlsm, freely available at academic.depauw.edu/~hbarreto/working. Cuba’s single-year population pyramid (Figure 1) offers an eyecatching display and, by utilizing simulation to evolve the process, we gain insight into the future prospects facing Cuba. In addition, this paper argues that the implications of an aging population for the economy need to be studied in much more detail.

Discussing teaching and learning at the university level, Marshall (1920, p. 822) said, “The springs of imagination belong to early youth: it is the greatest of all faculties; and in its full development it makes the great soldier, the great artist, the student who extends the boundaries of science, and the great business man.” Indeed, imagination, creativity, and discovery drive technological change and modern economic growth relies on waves of imaginative young people creating wonderful new ways to heal, entertain, and connect us.

It is no coincidence that, during the explosion of development enjoyed by the rich countries of the world in the last two centuries, population and educational attainment have been rising. There has been a constant stream of more educated young people replacing and revitalizing society, sending income per person ever higher. The innovation and technological progress that drives the engine of economic growth is itself dependent on imagination—the springs of which belong to the young. Creativity is less likely to be found in the old because their experiences discourage them from trying all possible solutions to a problem.

Furthermore, parents are willing to undertake heroic and expensive efforts on behalf of their children. Parents deny themselves present consumption to provide a better future for their children. Economies without this kind of forward-looking orientation will invest less and grow more slowly.

Over the next decades, we will get data on how economies function in the presence of smaller cohorts of young people. Japan is a leader in this unfortunate race (see the Japan sheet in PopPyrCuba.xlsm) and the early returns are not promising. Their economy has not fared well after decades of superb post-WWII growth and no standard policy has managed to shake it out of its doldrums. Luckily, Japan is a rich, developed country. Cuba is not and it is facing the same demographic headwinds as Japan.

There do not seem to be any practical policy levers to pull. Mortality is essentially exogenous. We can safely expect small, continued improvement in health and longevity in countries all around the world. Fertility is the key variable here, but we do not understand it well (long-run prediction has been dismal), but there is no reason to expect a Cuban fertility boom. Many countries have tax credits, baby bonuses, parental leaves, and other supports, but these are small relative to the total cost of raising a child and even if they were effective, the Cuban government does not have the resources for ambitious programs to increase fertility. Immigration (the solution, however unwittingly, adopted by the United States) seems highly unlikely to help Cuba withstand the coming demographic storm. Any easing of barriers to movement on the part of Cuba or other countries (especially the United States), would seem to exacerbate Cuba’s demographic challenge since more young adults are likely to leave Cuba than enter.

Viewing the number of children as a choice variable that responds to incentives leads to the realization that family planning is an outstanding example of an externality—a cost or benefit not taken into account by the decision-maker. The usual examples in economics involve pollution and education—the former a negative and the latter a positive externality. Standard economic theory says that because negative externalities result in too much of a good or service, we should tax them; but we subsidize positive externalities because they lead too few resources allocated in a given area. The optimal tax or subsidy would close the gap between private and social costs and benefits. This framework was developed by Pigou (1920). He supported taxing sellers of alcoholic drinks, zoning laws, and other government interventions as necessary measures to correct what would come to be known as market failures—misallocation of resources in the presence of a market imperfection such as monopoly or externalities. 1

Since parents do not capture the societal benefits of children, which are a function of the population’s age-distribution, they do not include these benefits in deciding how many children to have. Countries with inverted population pyramids are in a situation in which too few children are being produced and there is no effective way to signal the need for an increased quantity to individual decision-makers. The externality, in which the full benefit (to society) of having a child cannot be captured by its parents, prevents the system from self-correcting.

Absent a sea change in attitudes toward children, a reduction in the economic penalties women must pay to have children, or a technological revolution in how we produce human beings, we should expect that relatively low fertility rates will persist in Cuba and many other countries. The adjustment as population pyramids invert worldwide will not be easy. Cuba, with a weak economy and an especially large elderly cohort, seems to be in a dire position as it becomes the island of the old.