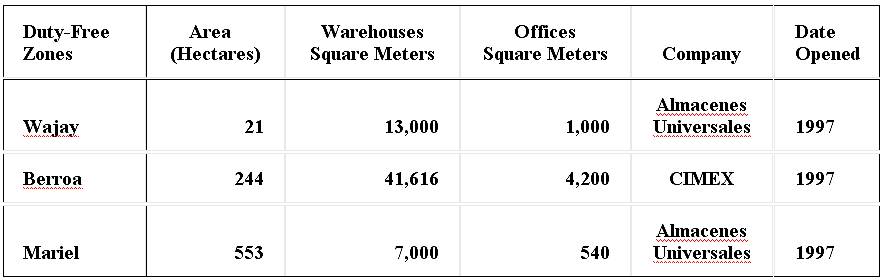

By Emilio Morales and translated by Joseph L. Scarpaci, Miami (The Havana Consulting Group). Original Essay here: The Mariel Special Zone The November 1 opening of the Mariel Special Economic Zone (ZEDM in Spanish) by the government of Raúl Castro is part of the so-called ‘economic model updating’ that seeks to attract fresh foreign capital to Cuba.A first step is the inauguration of the ZEDM Regulatory Office to receive and evaluate investment bids. Representatives from some 1,400 firms from 64 countries will get a chance to learn more about these investment opportunities when they attend the XXXI Havana International Fair from November 3 – 9. The special zone plays a key role in driving the government’s economic reforms, which have become the top priority. After the failures of the socialist economy over some five decades, the government leadership has little choice but to restructure the economy’s strategic sectors. Nothing short of a gradual opening towards a market economy, and shrinking the public sector, are key elements in this transformation. Second Stage Reforms Reforms seem to be headed towards stage two. Recently, 70 cooperatives outside of the agricultural sector came into operation and the number of approved self-employment jobs has risen to 201. The new Mariel project follows in the path of the Duty-free Zones (Zonas Francas) launched in the 1990s, and played an important role in attracting foreign investment. It is important to remember that such investment brought Cuba out of the so-called Special Period. However, those Duty-free Zones were eliminated in the middle of the last decade when the government of Fidel Castro did an about-face and re-centralized parts of the economy. The current investment climate is clouded with uncertainty because of the current state of the Cuban economy and the condition of its main trading partner, Venezuela. That is why this new zone, built at an estimated cost of some $900 million USD, faces a daunting start. Recalling Recent Memories Let’s take stock of what led up to this mega-project. The sole purpose of the Duty-Free Zones (ZF in Spanish) born out of Law Decree 165 in 1996 was to attract foreign investment. Operators in the ZFs were spared import tariffs on manufacturing and assembling, or on processing finished or partially-finds goods. Cuba’s competitors back then were from the Dominican Republic, Mexico, and a few Central American companies. In all, there were some 65 ZFs in the region and they produced footwear and leather goods, candy, electronic goods, plastics, and textiles. These products were largely destined to the United States, whose market has been off limits to Cuban products since 1960. The first three ZFs in Cuba appeared in 1997. The largest area was in Mariel, followed by Berroa (near the Havana port), and the smallest one, Wajay, was close to the José Martí International Airport in the southern section of the capital. Of the 243 operators in the ZF, about two-thirds were involved in trade, a fifth were in services, and 14% was in manufacturing. The latter category included the technology sector such as software, industrial projects, and machinery. Wajay had 120 operators, followed by Berroa (91) and Mariel (32). Spain (62) and Panama (43) had the largest number of companies in these duty-free zones. Foreign investment and operations in the ZFs peaked in 2002 with some 400 joint-venture and strategic alliances that brought just under $3 billion USD in investment. Starting in 2002, companies started closing in these zones and foreign investment tapered off. By 2008, only 200 firms operated there and business tapered off.  Three Strategic Sectors The Cuban equivalent of the U.S. Federal Register – the Gazeta Oficial No. 26 of 2013— recently stated the zones were “to promote the increase of infrastructure and activities to expand exports, import substitution, high-tech projects [and] generate new sources of jobs that contribute to the nation’s progress” (our translation). This pronouncement marks the second time in 20 years the government has tried to implement duty-free zones, and could strengthen three strategic sectors.

Three Strategic Sectors The Cuban equivalent of the U.S. Federal Register – the Gazeta Oficial No. 26 of 2013— recently stated the zones were “to promote the increase of infrastructure and activities to expand exports, import substitution, high-tech projects [and] generate new sources of jobs that contribute to the nation’s progress” (our translation). This pronouncement marks the second time in 20 years the government has tried to implement duty-free zones, and could strengthen three strategic sectors.

- Depwater oil exploration and extraction to become a crude-oil proicessing center.

- High-tech industrial parks for all kinds of products.

- Container storage and distribution center.

Explore or refine oil? This idea draws on the relative location of Cuba and the port of Mariel. Researcher Jorge Piñón points out that Mariel is strategically located at the crossroads of basins in the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea, where 49% of the hemisphere’s crude oil production, and 59% of its refining capability, are located. Moreover, Mariel sits at the doorstep of the world’s largest consumer and importer of oil: The United States. Considerable planning preceded the decision to commence deep-water oil exploration over the 112,000 square kilometer area of the Economic Exclusive Zone (ZEE in Spanish) just north of Cuba. But oil was not located and, in the medium run, there is just a small chance that Mariel will become a refinery center. In that scenario, there are plans to construct at the port of Mariel, 45 kilometers west of Havana, a huge warehouse center. It would also mean reviving super-tanker facilities at the port of Matanzas, the pipeline linking Matanzas and Cienfuegos (the latter, on the south-central coast), and expanding the recently upgraded oil refinery in Cienfuegos. The latter will increase daily processing from 65,000 to 150,000 barrels daily. All that depends on Venezuelan financing. Producing Goods and Services The second objective is to convince foreign investors to produce high-value goods and services in Cuba that can then be exported. To that end, the Cuban company ZDIM S.A., a subsidiary of the Cuban Revolutionary Armed Forces holding company, GAESA, has been created. ZDEM aims to link myriad development and industrial sectors via road, rail, and high-level communication networks. The strategy entails creating maquiladoras –low-cost and skilled labor clusters—to produce high-value added goods such as appliances, computers, construction materials, exportable biotechnology products, and even automobile assembly. A canning and packaging industry is also expected to support the Cuban domestic and export markets. Even though foreign companies operating in these zones will be exempt from salary and wage taxes, free of taxes on earnings for 10 years, as well other incentives, these measures are insufficient because they rely on traditional barriers of contracting labor through a government agency. Licensure to operate in the zone still relies on government agencies, and therein is the danger of a cumbersome and highly bureaucratic approval process for investors. The Container Business A third objective is a modern facility for dispatching and warehousing maritime and truck containers. Mariel would receive cargo ships that presently operate out of the aged and inefficient port of Havana. In turn, the capital city’s port would house cruise ship and recreational boating and sailing. Ambitious port expansion plans at Mariel are undoubtedly linked to the renovated Panama Canal, which will be completed in 2015. All this bodes well for maritime traffic throughout the Caribbean, which is poised to do substantial business with the break-in-bulk activities related to the gigantic ships known as Post Panamax. PSA International from Singapore will administer Mariel’s facility and will become the main port for Cuban imports and exports. A 2,000-meter long dock will be able to handle deep-water vessels and up to 3 million containers annually. The initial stage will develop the first 700 meters of berths and a storage capacity of 1 million containers per year. By 2014, it should be able to receive cargo ships bound for ports elsewhere in the Caribbean and the Americas. Installations include warehouses, could storage, fuel storage tanks, food distribution facilities, and other services. A highway and rail network will connect this, potentially the most important port in Cuba, with existing networks to guarantee the flow of goods. From Dream to Reality In theory, the Mariel project can only be viable over the long term. In the short term, however, it faces serious obstacles. First, ZEDM faces competition from similar installations in Panama, Jamaica, and elsewhere in the Caribbean basin and Central America. That competition is already tried and tested and operates with competitive prices. Significantly, they are in a better position to develop trade with the main market in the region: the USA. The Cuban project will be constrained by the U.S. trade embargo that prohibits ships that visit any Cuban port from entering U.S. territorial waters within six months. Accordingly, the zone’s reliance on large foreign investment will require those foreign businesses to stay on the island for a long time to recover their costs and turn a profit, and those investors will also be constrained by the embargo regulations. It is difficult to forecast the long-term investment successes in this first stage because of these risk factors. Instead, medium-term investments from Cuba’s main business partners –China, Brazil and Venezuela—are more likely. The zone’s development will require more flexible and open laws than the ones just launched. That means a new Foreign Investment Law, which was announced by Raúl Castro at the beginning of the year, but was inexplicably postponed until this week. Novel amendments to the existing legislation might allow for the Cuban exile community to invest or to exert pressure on the U.S. congress to lift the embargo. But let’s not deceive ourselves: The ZEDM has been conceived and designed all along with an eye on U.S. business investment. That is the same motivation behind Brazilian wagers and is the bait that will attract other investors. Havana in November 2013 has become a mid-summer night’s dream.

Mariel

Brazil is funding this project because they are interested in having a staging zone for their trade with Europe. This project has nothing to very little to do with future prospects of trade with United States or investments by the Cuban community….