By Arch Ritter

Cuba’s Oficina Nacional de Estadisticas (O.N.E.) recently published the 2010 Edition of the Anuario Demográfico de Cuba 2009, available on line here: http://www.one.cu/anuariodemografico2009.htm. A wide-ranging listing of the web publications on demography and population is located at this address: Oficina Nacional de Estadisticas, LA POBLACION CUBANA . Comprehensive statistical information for Cuba is available quickly, comprehensively. ONE’s coverage and presentation of demographic statistics has been improving steadily in terms of quality and timeliness. (In contrast, basic information on the economy such as unemployment, the consumer price index, and GDP is opaque, minimalist, and not clearly defined.)

Numerous useful and interesting insights into Cuba’s development, past and prospective, are apparent in the ONE data – and other demographic sources. A few are mentioned here.

1. Cuba’s Seasonal Conception Puzzle

An interesting phenomenon. of which I have been unaware. is the seasonal character of the numbers of births in Cuba – and of course the causal seasonality of conception rates. As Chart 1 illustrates, births peak from August to December but decline sharply during the months of February to June. This means that Cuba’s amorous months of high conception levels are from about December to April.

One can venture a number of guesses as to why this might be the case. For example, perhaps the cooler weather of Cuba’s winter months is more conducive to activities related to conception. Or maybe there is greater optimism and dynamism during the more prosperous times of the tourist high season. If anyone has clearer insights into this phenomenon, please let me know!

Chart 1 also shows increasing numbers of births from 2007 to 2009.

2. From Baby Boom to Baby Bust and Beyond?

2. From Baby Boom to Baby Bust and Beyond?

From 1960 to 1970 Cuba experienced a major “baby boom” with fertility rates rising to around 4.5 children per woman on average Chart 2. This may reflect the improvement in living conditions for many families, improved medical facilities and perhaps greater optimism about the future, leading women and families to choose to have more children during the first decade of the Revolution. As is well known, however, the fertility rate began a long descent to levels a good deal below the minimum necessary for long-term population stability which is considered to be around 2.2 children per woman. This baby “bust” commenced in 1970 and has continued to 2009, bottoming out at 1.39 children per woman in 2006 but rising somewhat to 1.70 in 2009. Cuba’s demographic experience is similar to that of numerous higher income countries such as Spain, with a fertility rate of 1.6 in 2005-2010: Italy, 1.4 ; Portugal, 1.4; Russia, 1.5; Canada, 1.6 and Germany 1.3.)

The causes of the declining fertility rates in Cuba undoubtedly included similar factors to the experience of other countries: higher female labor force participation rates (so that the income sacrifice for additional children was higher), better pension systems (so that one’s children were no longer necessary for income-support during old age), reduced opportunities for employing children as income earning assets due to urbanization and increased schooling, different career aspirations for women, easy availability of contraception including abortion etc.

The causes of the declining fertility rates in Cuba undoubtedly included similar factors to the experience of other countries: higher female labor force participation rates (so that the income sacrifice for additional children was higher), better pension systems (so that one’s children were no longer necessary for income-support during old age), reduced opportunities for employing children as income earning assets due to urbanization and increased schooling, different career aspirations for women, easy availability of contraception including abortion etc.

The impact of the changing fertility rates can then be observed in the 2010 population pyramid (Chart 3.) The 1960-1975 “Baby Boomers” reached age 40 to 50 during the 2000s leading to the large cohorts in the 2010 pyramid. But since 1970, the declining fertility rate has led to ever-narrowing cohorts of younger age groups. Even the demographic “echo” of the 1960-1970 cohort was muted.

Chart 3 Cuba’s Population Pyramid, 2010

The consequences for Cuba of an aging population also are similar to those for other countries, though some other high income countries, large scale immigration changes the picture. The main consequences are:

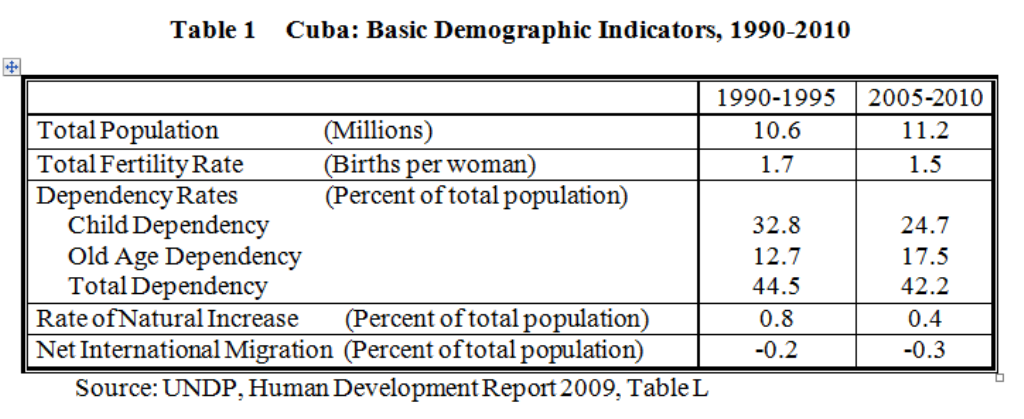

- The Old Age Dependency rate increased by almost 40% over the 1990-2010 period. Child Dependency rates declined by about 30% in the same period, reflecting the declining fertility rate. (Table 1.).

- The aging population will cause the Total Dependency Ratio (the sum of Child and Old Age Dependency as a proportion of the total population) to increase in future, burdening the economically active population for the support of pensioners and their health care.

- The “aging population” in time will become a “dying population.” The population, previously increasing or stable, will decline sharply when the “baby boom” cohorts hit age 65 or so in 10 to 15 years. This could be modified by compensating changes in fertility or international migration, but not in life expectancy which is unlikely to rise much further in future..

- The “Total Dependency Ratio” has been particularly low during the years when Child Dependency declined but the large “Baby Boom” age cohorts were still of working age. It is now at 42.2% (Table 1). Consequently the economically active population between age 20 and 60 as a proportion of the total population has been large.This so-called “demographic dividend” or “demographic window of opportunity” normally provides a stimulus to growth and development as in China. However, in Cuba’s case, it is passing quickly and so far has been partly wasted as it has been underemployed in low productivity activities.

Emigration

The Anuario Demográfico de Cuba 2009 also provides comprehensive information on internal migration and some general figures for external migration. Emigration numbers are illustrated in Figure 4. The “Special Period” since 1994 has been characterized by a steady hemorrhage of emigration. While ONE does not present information on the sociological character of the emigrants, casual observation suggests that they are well educated, entrepreneurial and perhaps disproportionately in the early adult 18 to 35 age grouping.