Time Magazine, William M. LeoGrande and Peter Kornbluh, 11/26/16

No foreign leader was more associated with conflict and confrontation with the United States than Fidel Castro. His legendary defiance and lengthy tirades against U.S. “imperialism” became an integral part of his lengthy reign in power. He made a political career by appealing to nationalism, wrapping himself in the Cuban flag and “hitting the Yanquis hard.” He aligned Cuba with the Soviet Union, Washington’s global adversary during the Cold War—an alliance that brought the world to the brink of nuclear annihilation during the 1962 missile crisis. Behind the scenes, however, the historical truth of Fidel Castro’s relationship with the United States is far more complicated.

The long saga of Fidel Castro’s confrontation with the United States began in 1958 when Castro and his small guerrilla band were still in the Sierra Maestra mountains fighting against General Fulgencio Batista’s dictatorship. Planes supplied to Batista’s air force by the United States dropped bombs and fired rockets at the guerrillas and their peasant supporters, enraging Fidel. The planes symbolized not only Washington’s years of support for the brutal Batista regime, but U.S. political and economic domination of Cuba dating back to the Spanish-American War. From the Sierra, Castro wrote to confidante Celia Sánchez, “When this war is over a much wider and bigger war will commence for me, the war I am going to wage against them [the United States].”

Yet when the revolution triumphed in January 1959, Castro harbored guarded hope that Washington might accept his vision of a new Cuba—less dependent on the United States and built on social justice. “At that time, we believed the revolutionary project could be carried out with a great deal of comprehension on the part of the people of the United States,” Castro told journalist Lee Lockwood, explaining why he came to the United States in April 1959. “[I went] precisely in an effort to keep public opinion in the United States better informed and better disposed toward the Revolution.”

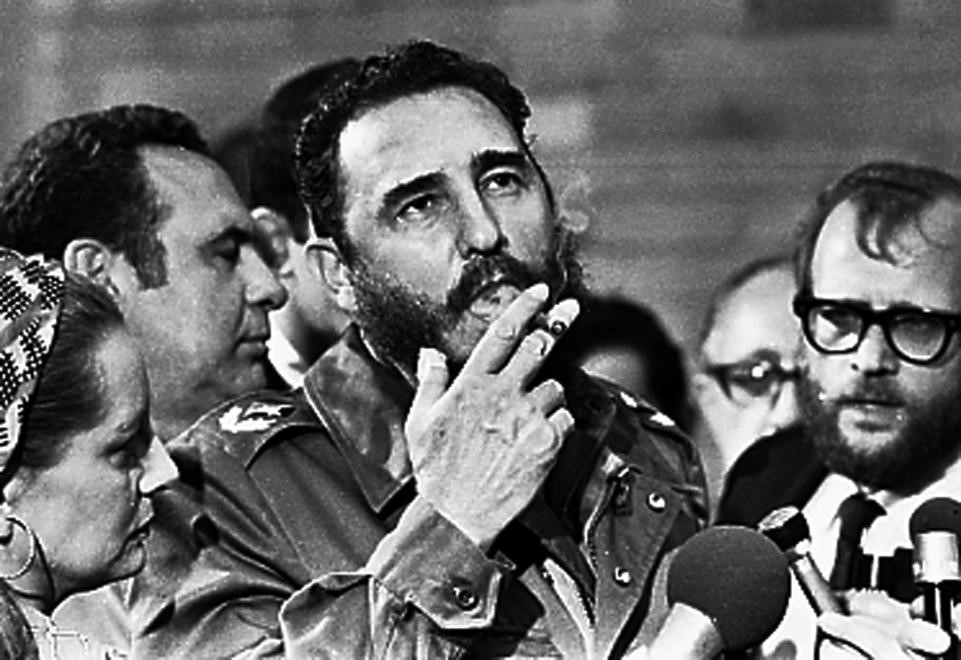

Then-Cuban Prime Minister Fidel Castro smokes a cigar during interviews with the press during a visit of U.S. Senator Charles McGovern in Havana in this May 1975 file photo. Reuters

Then-Cuban Prime Minister Fidel Castro smokes a cigar during interviews with the press during a visit of U.S. Senator Charles McGovern in Havana in this May 1975 file photo. Reuters

“Fidel went to the United States full of hope,” recalled his press secretary, Teresa Casuso. The public response was overwhelming. Everywhere Fidel went, he was met by cheering crowds. Fifteen hundred people were on hand when he arrived at Washington National Airport; 2,000 greeted him at Penn Station, New York; 10,000 turned out to hear him speak at Harvard; and 35,000 attended his outdoor address in Central Park. Fidel was delighted. “This is just the way it is in Cuba,” he marveled, wading into the crowds to shake hands.

The meetings between Castro and suspicious U.S. officials were less successful. President Dwight D. Eisenhower left town to avoid meeting Castro, delegating that task to Vice President Richard Nixon. Nixon came away from his two-and-a-half-hour meeting with Fidel convinced that Castro was inexperienced, naive and dangerous. But Nixon also was impressed with Castro’s charisma, according to the secret report he sent to Eisenhower. “Whatever we may think of him he is going to be a great factor in the development of Cuba and very possibly in Latin American affairs generally,” Nixon wrote.

The possibility of reaching a modus vivendi between revolutionary Cuba and the United States proved fleeting, smashed on the twin shoals of Castro’s anti-American rhetoric and Washington’s intolerance of Fidel’s impudence. By late 1959, the CIA had already begun plotting against Castro. The era of confrontation followed, marked by the familiar litany of the Bay of Pigs invasion, the missile crisis, CIA assassination plots, Operation Mongoose’s secret paramilitary war and the economic embargo.

But throughout the ensuing half-century of hostility, Fidel Castro and successive U.S. presidents kept up a secret dialogue to deal with issues that required cooperation and, occasionally, to explore the possibility of rapprochement. Every U.S. president since Eisenhower engaged in talks with Cuba. And when each new U.S. president entered the White House, Fidel Castro sent out feelers– often privately through secret emissaries– to see whether reconciliation might be possible. More than once, he sent the new president a box of his best Cuban cigars to break the diplomatic ice.

Castro regretted his role in the breakdown of relations. “I must acknowledge that I may have had some responsibility for our first divorce,” Castro admitted to U.S. diplomat Wayne Smith. “In retrospect, I can see a number of things I wish I had done differently. We would not in any event have ended up close friends. The United States had dominated us too long. The Cuban revolution was determined to end that domination,” Fidel reflected. “Still, even adversaries find it useful to maintain bridges between them. Perhaps I burned some of those bridges precipitously.”

Over the years, secret talks between Havana and Washington produced a wide variety of agreements on issues of mutual interest. Periodic crises of uncontrolled migration led to a series of migration accords. Other agreements included an anti-hijacking agreement in 1973, a maritime boundaries agreement and an exchange of diplomatic missions in 1977, a Coast Guard agreement in 1978 and an agreement to fight narcotics trafficking in 1999.

Yet these successes never led to normal relations. Two serious attempts, during the presidencies of Gerald Ford (led by Secretary of State Henry Kissinger) and Jimmy Carter, ended in failure. In both instances, Washington was motivated by the futility of the policy of hostility, by pressure from U.S. allies and Congress, and by a hope that Cuba might be enticed out of the Soviet orbit. Although Castro wanted better relations with Washington, it was not his only foreign policy priority and he was willing to pay only a limited price to achieve it. The approaches that Kissinger and Carter set in motion were both disrupted when Cuba sent troops to Africa to defend allies from invasion, first in Angola, then in Ethiopia.

Kissinger was so shocked and offended that Castro would throw the entire architecture of détente into jeopardy and defy the United States this way that he ordered the Pentagon to prepare plans for bombing and blockading the island. “I think we are going to have to smash Castro,” he told President Ford in the oval office on February 25, 1976. “We probably can’t do it before the elections.”

“I agree,” the president replied. But Ford lost that election to Jimmy Carter and Kissinger’s plans to “clobber” Cuba were never implemented.

Instead, within weeks of his inauguration, Carter ordered his government to open a dialogue with Cuba to normalize relations. When Castro sent troops to Ethiopia, derailing those negotiations, some speculated that Fidel simply did not want better relations—that his heroic persona of David defying the imperialist Goliath was too valuable at home and abroad to sacrifice. Castro acknowledged that battling United States had its advantages: “If the United States makes its peace with us, it will take away a little of our prestige, our influence, our glory,” he admitted to U.S. journalists in 1985.

Yet even after Cuba’s involvement in Ethiopia, Castro sent secret emissaries to Washington to try to revive the normalization talks. Knowing President Carter’s commitment to human rights, Castro released more than 3,000 political prisoners without asking for any quid pro quo. A series of secret meetings followed, but faltered over the U.S. demand that Cuba withdraw from Africa. Castro was simply unwilling to sacrifice the rest of his foreign policy as a quid pro quo for improving relations with Washington.

Fidel could never understand—or at least, could never accept—why Cuba should not to be free to help its friends, just as the United States did, and why bilateral relations should be held hostage to Cuba’s policies in Africa. In reality, however, Cuba’s role in Africa shoring up socialist governments with Soviet logistical support tilted the global balance against the United States in the Third World—something no president could ignore.

After the Cold War, Castro’s interest in improving relations with Washington grew. As Cuba sought to diversify its economic relations after the loss of Soviet aid, the potential for trade and investment from the United States was enticing. Absent the imperative of the Cold War, however, Washington was less interested in relations with Cuba, good or bad. The rise of the powerful Cuban-American lobby in the electoral battleground state of Florida transformed the Cuba issue from one of foreign policy to one of domestic politics.

And so it remained for the next 20 years. President Bill Clinton tried to improve relations at the margins by expanding societal contacts, including remittances from Cuban-Americans to family still on the island, travel opportunities and cultural and educational exchanges. But Clinton was torn between his recognition that the hostility policy no longer made sense, and his politician’s instinct to break the Republicans’ electoral lock on Florida. “Anybody with half a brain could see the embargo was counterproductive,” he told a confidante in the Oval Office. However, “Republicans had harvested the Cuban exile vote by snarling at Castro.” Clinton understood the political imperative to snarl, and ultimately placed a higher priority on electoral votes in Florida than he did on relations with Havana.

Then-Cuban President Fidel Castro laughs during the year-end session of the Cuban parliament in Havana in this December 23, 2005 file photo. Reuters

When Cuba shot down two small planes that had violated its airspace, killing four Cuban-Americans from the anti-Castro group Brothers to the Rescue, Clinton signed the Cuban Liberty and Democratic Solidarity Act of 1996 (also known as Helms-Burton) which wrote the embargo into law. From then on, no president could simply lift the embargo and normalize relations with Cuba at his discretion; that would now require an act of Congress.

Over the years, as Fidel Castro jousted with a succession of 10 U.S. presidents, he managed to raise Cuba’s international standing dramatically. He repaired relations with Latin America, which initially supported the U.S. embargo but by the turn of the century was virtually unanimous in condemning it and demanding Cuba’s reintegration into the inter-American community. Despite dramatic ups and downs, Castro rebuilt Cuba’s ties to Europe, also severed in the 1960s when the NATO countries followed Washington’s lead. In the 1990s, when Cuba opened up to tourism and foreign investment, Europe’s ties with Cuba expanded.

In the Third World, Castro’s activism on behalf of small, poor countries won him enormous prestige. “What Fidel has done for us is difficult to describe with words,” said South African President Nelson Mandela. “In the struggle against apartheid he did not hesitate to give us all his help.” Cuba was twice elected to chair the Movement of Nonaligned Nations, and sent thousands of medical personnel abroad on aid missions. He repaired relations with China and Russia.

But the main prize always lay just beyond Fidel’s grasp. He was never able to normalize relations with the United States, never able to win recognition and acceptance for himself and for the Cuban revolution. The task of repairing relations with Washington fell to his brother Raúl, who reached the dramatic agreement with President Barack Obama last December to take the first step toward normality—restoring diplomatic relations broken in January 1961.

Fidel Castro deserved his share of the blame for the half-century of antagonism between Cuba and United States, but he must also get some of the credit for making reconciliation possible. He survived Washington’s best efforts to overthrow him, demonstrating the futility of the policy of hostility, and his policies abroad rallied literally the entire world against the U.S. embargo. The diplomatic cost Washington was forced to pay, especially in Latin America, ultimately proved too costly and convinced President Obama that the time had come to open a “new chapter” in U.S.-Cuban relations. By abandoning more than five decades of a policy of hostility and replacing it with a policy of engagement and dialogue, the United States has finally accepted Cuba as a fully sovereign and independent country. That is, after all, what Fidel Castro wanted from the beginning.

William M. LeoGrande is professor of government at American University, and Peter Kornbluh is director of the Cuba Documentation Project at the National Security Archive in Washington, D.C. They are co-authors of Back Channel to Cuba: The Hidden History of Negotiations between Washington and Havana (University of North Carolina Press, 2014).