Fighting Ebola: A new case for U.S. engagement with Cuba

Original Article: http://tbo.com/list/news-opinion-commentary/fighting-ebola-a-new-case-for-us-engagement-with-cuba-20141028/

BY ARTURO LOPEZ-LEVY

Special To The Tampa Tribune; October 28, 2014

The simple fact that Cuba and the United States are in the same boat fighting the Ebola epidemics in Western Africa demonstrates how the level of conflict between the two countries is irrational. While Havana and Washington have considerable differences — and no parallel efforts against a common enemy as Ebola can bridge them — it is evident that narratives of suspicion and intransigence prevent such joint efforts for the benefit of both countries and the world in general.

But, words matter. The recent statements by John Kerry and Samantha Power praising what Cuba is doing to fight Ebola in Africa on behalf of the U.S. State Department — as well as the declarations by Fidel and Raul Castro that Cuba would welcome collaborative efforts on Ebola with the United States — show that a revision of the bilateral relations is long overdue.

President Obama now needs to apply the dictum of his former chief of staff, Rahm Emanuel, and not waste the opportunity presented by the Ebola crisis. Cuba and the United States should advance long-term cooperation in international health efforts under the auspices of the WHO.

Political leadership in the White House and the Palace of Revolution would transform a fight against a common threat into joint cooperation for the advancement of human rights (the right to health is a human right) all over the developing world and the national interests of the two neighbors.

Political conditions are ripe for such turn. Americans strongly support aggressive actions against Ebola and would applaud a president who put lives and medical cooperation with Cuba above ideology and resentment.

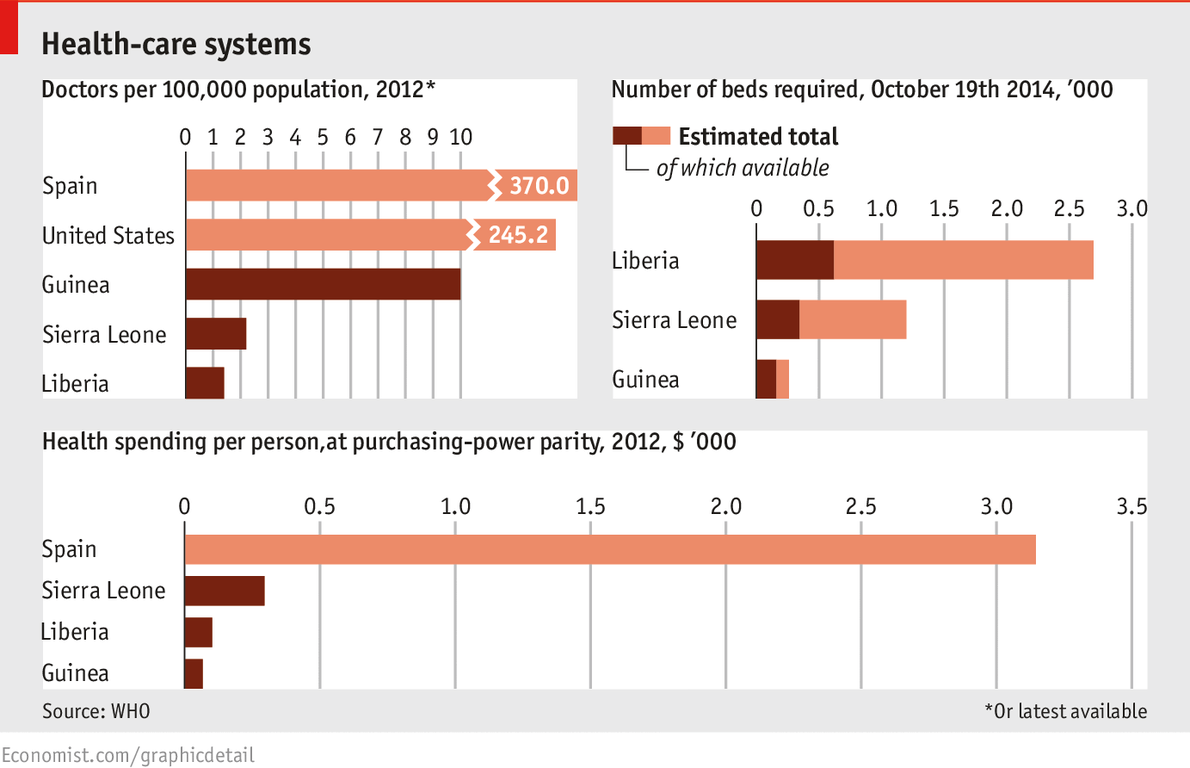

As more information comes out about Cuba’s international health effort, it is becoming clearer how unreasonable it is to assume that all Cuban presence in the developing world is damaging to U.S. national interests. The more than 40 000 Cuban doctors and health personnel working in 80 countries are playing a key role to improve human development and protect the world from the spread of Ebola and other contagious diseases.

During the Bush administration and even under Obama, the United States spent lavishly to support groups in Miami that focus on undermining Cuba’s international health presence in Africa and Latin America.

The U.S Cuban Medical Professional Parole Immigration Program (CMPP) is reminiscent of the Cold War. The program encourages Cuban doctors to abandon their contracts in third countries and immigrate to the United States.

Washington’s ideology-driven hostility toward Cuba’s international health efforts has further divided the United States from other democratic countries. The trouble for Miami die-hard Cold Warriors is that examples of how Cuba shares the burden and merits of international health efforts with U.S. allies are expanding. Cuba is cooperating with several institutions of the European Union, Brazil, Canada and Norway in projects of medical education on the island, and in Haiti and other countries. The programs might even grow as result of the current negotiation in Brussels between the EU and Cuba for a comprehensive agreement on cooperation and political dialogue.

The good news is that two former U.S. presidents, Jimmy Carter and Bill Clinton, have talked positively about Cuba’s health achievements and international programs. President Carter and former first lady Rosalyn even visited Cuba’s Latin American School of Medicine in 2002. In a meeting with then Cuban minister of health Carlos Dotres, Mrs. Carter mentioned that their presidential center’s Global Health program would like to collaborate with Cuba’s international medical educational assistance. There is no moral, political or national security explanation for why such humanitarian endeavors are not happening already.

As a senator and presidential candidate, Obama was one of the loudest critics of looking at Cuba through the glasses of the Cold War. As a president, it isn’t enough for him just to retune the same policy of embargo implemented by his predecessors. He must adjust the official U.S. narrative about post-Fidel Cuba: It is not a threat to the United States but a country in transition to a mixed economy, and a positive force for global health.

Arturo Lopez-Levy is a visiting lecturer at Mills College in California and a PhD candidate at the Josef Korbel School of International Studies at the University of Denver.

Ebola Could Bring U.S. and Cuba Together

By: Ted Piccone, Brookings Institution

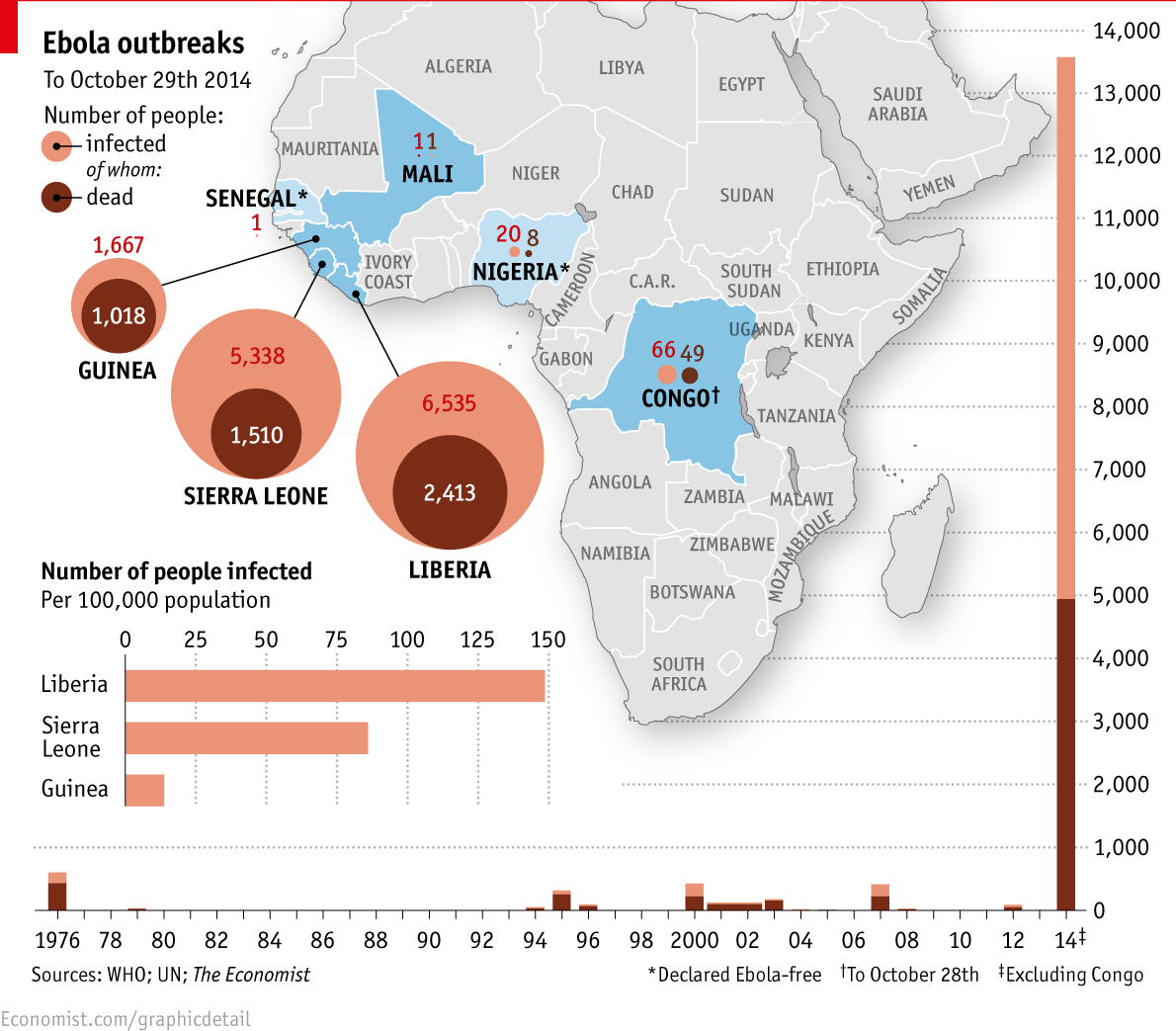

On October 28, the United Nations General Assembly voted overwhelmingly for the 23rd year in a row to condemn the United States’ tough embargo on Cuba as a unilateral interference in free trade. Coincidentally, the UN system is tackling the devastating spread of the Ebola virus in West Africa and urging states to contribute medical and financial resources to stem the outbreak.

Ironically, Cuba and the United States have led the world in responding to the call for help, rushing hundreds of medical workers, military personnel, equipment, and other resources to Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Guinea to treat Ebola’s victims and prevent the epidemic from spreading. Could this be the moment for both countries to set aside their differences and join forces for the greater good?

The answer is a qualified yes. The onerous U.S. embargo poses no obstacles to such cooperation, and in any event, bilateral assistance for humanitarian reasons, including food and medicine, is a well-established exception to the rule. So there is no legal reason why U.S. personnel could not work alongside Cuban doctors and nurses in a third country to provide humanitarian aid to the stricken.

Moreover, there are precedents for this kind of cooperation. In 2010, in response to the devastating earthquake in Haiti, American and Cuban personnel worked together to provide emergency care, including the provision of U.S. medical supplies to field hospitals staffed by Cuban doctors.

Cooperation was so positively received that the two sides launched high-level discussions about a joint project to build a new hospital in rural Haiti to be staffed in part by Cuban medical personnel.

Yet, as in so many other instances, cooperation between Havana and Washington broke down. This time, the dispute concerned a Bush-era program allowing Cuban doctors and other health personnel easy immigration into the United States. Cuba insisted that the program be dropped.

Already, nearly 1,600 Cuban health workers have taken advantage of the enticement, which undermines Cuba’s well-regarded health-care system, a pride of the revolution.

Proponents of the expedited visa program, on the other hand, argue that these medical workers are forced to work for Cuba’s public health service under the island’s restrictive labor laws. Given their specialized medical training, they also have a much harder time than other Cubans gaining permission to leave the island, even under the more relaxed travel policies that Cuba adopted in 2012.

U.S. President Barack Obama has a unique opportunity to show the world that the United States can rise above old hostilities for the sake of saving lives. He can immediately use his executive authority to suspend the discretionary parole program for any Cuban medical worker who is deployed to West Africa in response to the Ebola outbreak, and thereby stem Cuba’s professional brain drain.

Cuba has sent more than 50,000 medical personnel to 66 countries (more than those deployed by the G7 combined), and is now the biggest single provider of health-care workers to the Ebola crisis in West Africa. For their part, the Cubans could address concerns about the nature of their highly touted medical missionary work by giving participants in their medical brigades the option of serving abroad as volunteers, not conscripts, at no cost to their careers if they say no, and with higher pay if they say yes.

The timing for such a move is ripe. Since Obama eased the embargo in his first term by allowing more Cuban Americans to visit and send remittances to their relatives, and facilitating other categories of travel to the island, people on both sides of the Florida Straits are reconnecting in myriad ways, slowly rebuilding the bridge that has long divided the two countries.

Both sides have begun cooperating in modest but pragmatic ways, in such areas as counter-narcotics, aviation security, marine environmental affairs, and migration. This would be one additional step on the path toward the reconciliation that a majority of Americans, including Cuban Americans in Florida, want and deserve.

The next steps, however, will be even more important. After the November elections, President Obama should signal his willingness to improve relations with Cuba by ending more travel and remittances restrictions, expanding support to Cuba’s emerging private sector, and engaging in high-level talks to remove Cuba from the U.S. list of state sponsors of terrorism.

Action on key cases involving citizens held in prison in both countries should be on the agenda as well, but not as a precondition for talks. And, assuming cooperation in West Africa goes well, President Obama should broaden the scope and timeline of the suspension of the medical parole program.

Now is the time to take these steps, before President Obama travels to the Summit of the Americas in Panama in April. There, he and Cuban President Raúl Castro should finally talk face-to-face, without preconditions, and set a path toward reconciliation through dialogue. It would be a great legacy for both presidents as they depart office in just a few years.

This piece was originally published by The Mark.